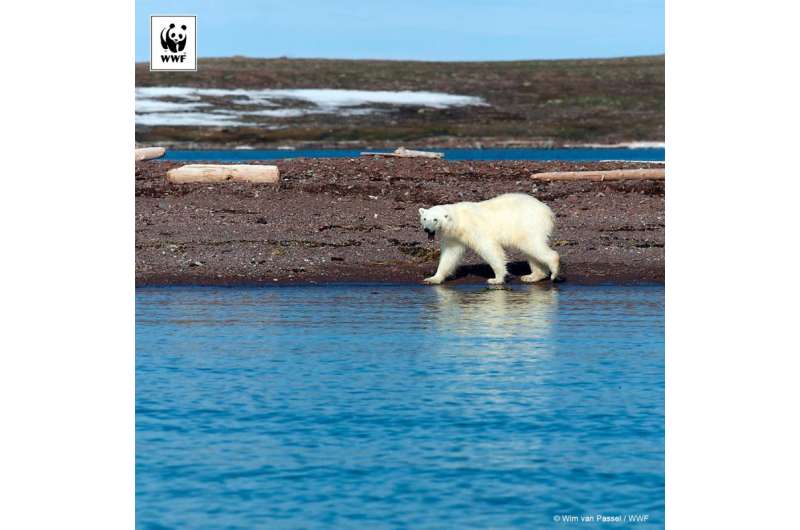

Historic low levels of Arctic sea ice signal trouble for Arctic wildlife

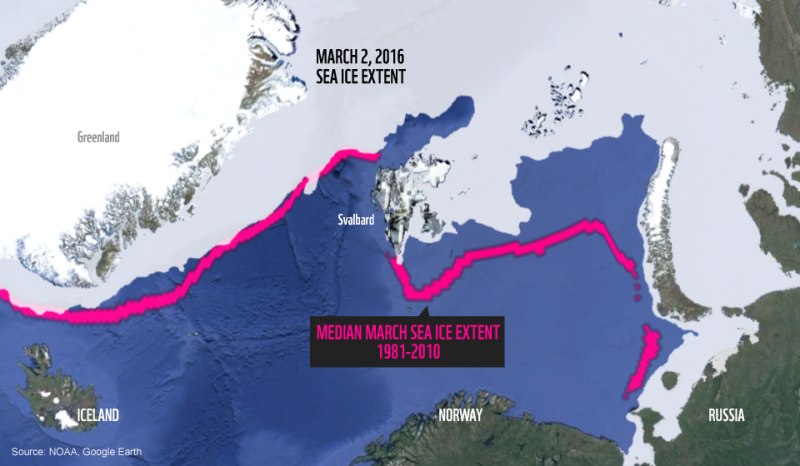

Following a record-breaking warm Arctic winter, Arctic Ocean sea ice looks set to hit a record low maximum level. The ice hit a maximum of 14,478 million km2 on the second day of March. If the ice does not grow any more this year, this will set a new record, beating the previous low maximum set last year.

Although a low maximum does not necessarily lead to a low minimum record in the late summer, it does have impacts on Arctic wildlife. New polar bear mothers emerging from a long fast in the dens where they gave birth over winter need quick access to sea ice to feed and regain their strength.

"This year is the most extreme I've ever seen," said Jon Aars, a polar bear researcher with the Norwegian Polar Institute whose field work on the Norwegian Svalbard archipelago is partly supported by WWF.

Aars expects that this spring he will find that fewer female polar bears even made it to shore to den.

"It is very bad in the more eastern parts of the archipelago, where we traditionally have had the most important denning areas. This means that it is very difficult for the bears to reach those areas," said Aars.

Aars also expects that the low ice conditions will have a negative effect on the polar bears' main prey, ringed seals, which need sea ice to give birth to their pups.

"This year marks another grim statistic in the continuing disappearance of Arctic sea ice, with major consequences for wildlife and weather in the northern hemisphere," said Samantha Smith, Leader of WWF's Global Climate and Energy Initiative. "If we needed reminding, we have it: Governments, businesses and cities must act immediately on their climate commitments from the UN negotiations in December."

Late last year, governments meeting in Paris adopted a deal that lays the foundation for long-term voluntary efforts to fight climate change. The Paris Agreement includes a long-term temperature goal of well below 2°C of warming and a reference to a 1.5°C goal, sending a strong signal that governments are committed to following the latest science.

The Paris Agreement is also the first agreement that joins all nations in a common cause on climate change based on their historic, current and future responsibilities.

"As the latest scientific findings from the Arctic show, there is no alternative to implementing climate commitments. We must stop the steady destruction of our planet's delicate ecosystems and

start building a new and renewable energy future," said Smith.

Last week, Canada and the United States agreed to several Arctic initiatives, underscoring the need to take action on both mitigating climate change and on Arctic conservation to reduce the impacts of change already being experienced.

On April 22, governments will meet at the United Nations in New York when the new global climate deal is opened for signature. This coincides with the global observance of Earth Day.

Provided by WWF