November 17, 2015 report

Researchers suggest modern gourds would not have survived without domestication

(Phys.org)—A team of researchers with members from several institutions in the U.K. and U.S. has found evidence that suggests that modern gourds would have gone extinct long ago if humans had not domesticated them. In their paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team describes their study of the history of gourds in the New World and why they needed domestication to survive.

Prior evidence has shown that plants of the genus Cucurbita, which includes pumpkins, gourds and squashes, flourished during the Holocene in areas where large mammals such as giant sloths, mastodons and mammoths roamed—the huge mammals not only trampled and grazed in such areas, clearing land that the plants needed to survive, but also dispersed their seeds via their dung—thus there's was a mutually positive relationship. But then things changed, the climate grew warmer and humans arrived with their advanced hunting skills—over time, the large mammals ceased to exist. The squash and gourds soon found it much more difficult to survive in overgrown vegetation and had little to no means of seed dispersal, which, the researchers suggest, means they would have all gone extinct had humans not begun to domesticate some varieties.

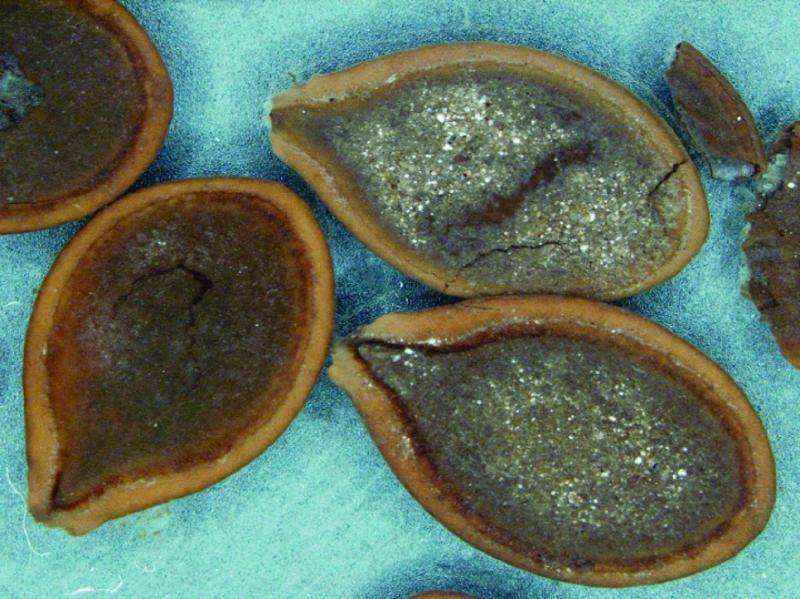

To come to these conclusions, the researchers studied gourd and other seeds found in preserved large mammal dung (going back 30,000 years), which revealed a wide variety of lost species. They also tested the degree of bitterness in ancient gourd skin and then compared what they found with the results of a genome study they conducted looking at bitterness sensitivity in 46 modern animals–they found that the ancient varieties were so bitter that they would have been toxic to very small mammals and unpalatable to those somewhat larger, leaving just the largest mammals able to consume Cucurbita. The evidence indicates that most Cucurbita species began to decline approximately 10,000 years ago, and that most of them eventually went extinct. Those that we favor today only survived because humans began using them first as containers and floatation devices for fishing nets, then later, as a food source, presumably as domestication led to sweeter varieties.

More information: L. Kistler et al. Gourds and squashes (Cucurbita spp.) adapted to megafaunal extinction and ecological anachronism through domestication, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2015). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1516109112

Abstract

The genus Cucurbita (squashes, pumpkins, gourds) contains numerous domesticated lineages with ancient New World origins. It was broadly distributed in the past but has declined to the point that several of the crops' progenitor species are scarce or unknown in the wild. We hypothesize that Holocene ecological shifts and megafaunal extinctions severely impacted wild Cucurbita, whereas their domestic counterparts adapted to changing conditions via symbiosis with human cultivators. First, we used high-throughput sequencing to analyze complete plastid genomes of 91 total Cucurbita samples, comprising ancient (n = 19), modern wild (n = 30), and modern domestic (n = 42) taxa. This analysis demonstrates independent domestication in eastern North America, evidence of a previously unknown pathway to domestication in northeastern Mexico, and broad archaeological distributions of taxa currently unknown in the wild. Further, sequence similarity between distant wild populations suggests recent fragmentation. Collectively, these results point to wild-type declines coinciding with widespread domestication. Second, we hypothesize that the disappearance of large herbivores struck a critical ecological blow against wild Cucurbita, and we take initial steps to consider this hypothesis through cross-mammal analyses of bitter taste receptor gene repertoires. Directly, megafauna consumed Cucurbita fruits and dispersed their seeds; wild Cucurbita were likely left without mutualistic dispersal partners in the Holocene because they are unpalatable to smaller surviving mammals with more bitter taste receptor genes. Indirectly, megafauna maintained mosaic-like landscapes ideal for Cucurbita, and vegetative changes following the megafaunal extinctions likely crowded out their disturbed-ground niche. Thus, anthropogenic landscapes provided favorable growth habitats and willing dispersal partners in the wake of ecological upheaval.

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

© 2015 Phys.org