Researchers discover strong break on cell division

The protein complex SWI/SNF that loosens tightly wrapped up DNA is also a strong inhibitor of cell division, at the time that cells take on specialized functions. Professor Sander van den Heuvel and PhD researcher Suzan Ruijtenberg (both from Utrecht University) discovered this important inhibitor function. How exactly cell division stops at the right time is not yet known in detail, but unhindered continuation of cell division is a major step to cancer formation. In one in five human tumours SWI/SNF is defective. This might play a role in the uninhibited division of tumour cells. The leading journal Cell published the discovery online on July 2. NWO funded this research through its Open Programme, which enables researchers to develop new lines of research based on their own insights.

Chromatin remodelling

SWI/SNF regulates the accessibility of the DNA. Within the cell, the long chains of DNA molecules are wound up into a far more compact form, called chromatin. Properly functioning SWI/SNF makes tightly wound up DNA a bit looser at the right moment and in the right place. As a result, genes needed for cell division for example, are made accessible (this enables cell division) or inaccessible (this inhibits cell division). This untangling of the DNA is called chromatin remodelling. When SWI/SNF does not function properly, chromatin remodelling is defective and uninhibited cell division can be the consequence. Several other systems are known that can partially inhibit cell division, but SWI/SNF was found to be the most important contributor to cell division arrest.

Explosive cell division

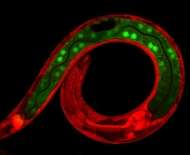

Ruijtenberg and Van den Heuvel studied the different cell division brakes using a transparent 1 mm long worm (Caenorhabditis elegans). This tiny animal is often used as a model system for unravelling complex life processes in humans. It is precisely known how often each cell will divide to allow a worm egg to grow into an adult animal. Under the microscope, this growth process can be easily followed from cell division to cell division.

In this study, the researchers modified the DNA of the worms in such a way that it was possible to sabotage (knock out) the genes for certain proteins in specific cells. Moreover, the animals were adjusted to emit fluorescent light. If a gene is knocked out, the production of the corresponding protein stops and the fluorescent colour of the cell changes from red to green. With this approach it can be seen exactly when a knocked-out protein is a cell division inhibitor: then large quantities of green fluorescent daughter cells arise.

Worm cells in which the researchers knocked out the known inhibitors did indeed divide more than normal. However, cell division only went truly out of control when the researchers knocked out SWI/SNF as well. Ruijtenberg: 'With these findings, we have shown that chromatin remodelling is incredibly important for controlling cell division.'

Future

This development of a knockout system, with which genes can be switched on and off at will, makes C. elegans an attractive model for cancer research and makes new research into the mechanisms of animal and human development possible. Suzan Ruijtenberg will defend her PhD thesis on this research on 16 September 2015.

More information: "G1/S Inhibitors and the SWI/SNF Complex Control Cell-Cycle Exit during Muscle Differentiation" DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.013

Journal information: Cell