Salinization of groundwater resources in Texas is a growing concern

(Phys.org) —Degrading potable groundwater quality is a growing concern in Texas, as about 15 percent of all domestic wells in the state are at risk due to high salinity, according to a recent Texas A&M AgriLife Research study.

The work of Dr. Srinivasulu Ale, AgriLife Research geospatial hydrology assistant professor, and Dr. Sriroop Chaudhuri, his post-doctoral research associate, both in Vernon, has been accepted for publication in the Science of the Total Environment journal.

The study, "Temporal Evolution of Depth-stratified Groundwater Salinity in Municipal Wells in the Major Aquifers in Texas," was completed using the Texas Water Development Board's groundwater quality database for the period from 1960 to 2010.

Groundwater withdrawal accounts for about 36 percent of Texas' municipal water supplies, according to Ale. However, a myriad of water quality issues have been reported from around the state, raising serious concerns over groundwater use due to a rise in concentration of sulfates, chlorides, fluorides, nitrates and total dissolved solids.

Total dissolved solids is a collective manifestation of all dissolved chemicals and is considered a measure of salinity and an overall indicator of water quality, relating to taste and palatability, he said.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency sets maximum and secondary contaminant levels for drinking water, with the secondary level being a non-enforceable threshold limit dealing mainly with aesthetics or odor, cosmetic or color, and technical effects – corrosiveness, staining, scaling and sedimentation, Chaudhuri said.

Water with total dissolved solids concentrations greater than the secondary maximum contaminant level of 500 parts per million can cause substantial damage to plumbing fixtures, he said. Levels above 1,000 and 3,000 parts per million are considered as brackish and moderately saline, respectively.

"In our study, we assessed spatial distribution of total dissolved solids in shallow, intermediate and deep municipal wells in nine major aquifers in Texas for the 1960s-1970s and 1990s-2000s periods," Ale said.

Previous hydrogeologic investigations of the Edwards-Trinity Plateau, Pecos Valley, Edwards Balcones Fault Zone Aquifer, Gulf Coast, Ogallala, Carrizo-Wilcox, Hueco-Mesila Bolson, Trinity and Seymour aquifers in Texas have also examined groundwater salinity, he said.

These studies, however, lacked depth-stratified long-term evaluation of groundwater salinization with specific reference to potable use, Ale said. The objective of this study was to offer a qualitative overview of the spatial, both horizontal and vertical, and temporal extent of groundwater salinization in light of regional differences in hydrochemical processes, or changes to the ambient water composition.

To achieve this goal, the study was divided into three subtasks: map the total dissolved solids concentrations in the aquifers at different well-depths; assess salinity based on drinking water quality standards; and highlight the major clustering of chemicals in certain aquifers that led to groundwater salinization.

"As the importance of groundwater resources continues to rise in the future; and as more of our freshwater reserves are affected by rising salinity and other harmful constituents, findings of this study will aid the groundwater and natural resources managers as well as general public to understand geographic distribution and relative extent of groundwater salinization of the state's drinking water resources and plan for appropriate management actions," Ale said.

Over time, groundwater salinization across the state has become more "structured," with certain regions showing remarkable consistency in water quality degradation due to a progressive rise in salinity levels, he said.

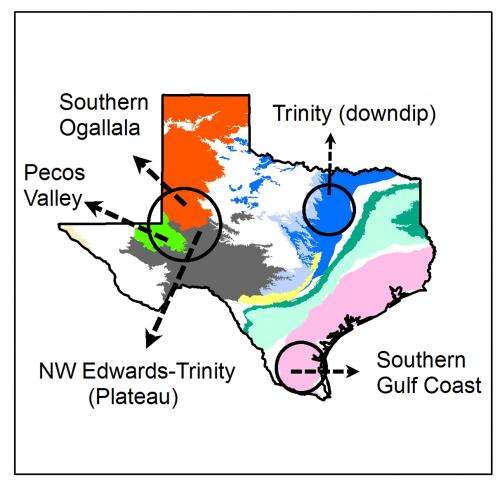

"We identified hot spots of groundwater salinization at shallow depths across vast regions of West Texas in the southern Ogallala, northwestern Edwards-Trinity and Pecos Valley aquifers; intermediate and deep depths in the southern Gulf Coast aquifer; and deep depths in North Central Texas in the Trinity region," Ale said.

Groundwater salinization is a complex process resulting from various natural and human-induced changes of ambient hydrologic conditions, Chaudhuri said.

"Interestingly, our study revealed that the causes of groundwater salinization differed across Texas, as reflected by noticeable regional differences in groundwater chemical composition," he said.

Ale said groundwater mixing via cross-formational flow between aquifers, seepage from saline plumes and playas, evaporative enrichment, hydrocarbon exploration activities and irrigation return flows led to groundwater salinization in West Texas.

In contrast, he said, ion-exchange processes in the North Central Texas and seawater intrusion coupled with salt dissolution and irrigation return flow in the southern Gulf Coast regions caused groundwater salinization.

For both time periods, the highest average groundwater total dissolved solids concentrations in shallow wells were found in the Ogallala and Pecos Valley aquifers, and those in the deep wells were in the Trinity aquifer, he said.

In the Ogallala, Pecos Valley, Seymour and Gulf Coast aquifers, about 60 percent of the observations from shallow wells exceeded the secondary maximum contaminant level for total dissolved solids in both time periods, which indicates persistent concern over potable water quality, Chaudhuri said.

In the Trinity aquifer, 72 percent of deep water quality observations exceeded the secondary maximum contaminant level in the 1990s-2000s, compared to 64 percent observations in the 1960s-1970s, he said.

In the Ogallala, Edwards-Trinity Plateau and Edwards Balcones Fault Zone aquifers, extent of salinization decreased significantly with well depth, indicating surficial salinity sources.

Among all the major aquifers of Texas investigated in this study, the Edwards Balcones Fault Zone aquifer appeared to have the "best" potable groundwater quality with the lowest salinity levels and concentrations of major inorganic constituents, Ale said.

A major challenge faced during the course of this research was the decreasing number of observations over the years and a lack of adequate spatial representation of groundwater quality data for each aquifer, he said. It was therefore necessary to establish a more intense and "informed" water quality monitoring network, especially for regions that registered long-standing salinity issues.

Ale and Chaudhuri concluded in their study that management strategies to address high salinity issues in the state should be devised based on detailed site-specific analysis of factors influencing groundwater hydrochemical evolution supported by more intensive water quality monitoring and assessment.

In this regard, both groundwater and surface water quality monitoring is necessary to establish a detailed water budget and salt mass balance, they said. Domestic well owners should also be encouraged to monitor water quality at regular intervals and be advised about appropriate well-head maintenance and protection strategies.

For agricultural regions, mainly in the Ogallala, Seymour and southern Gulf Coast aquifers, appropriate irrigation management strategies, based on local recharge, water-level changes and evapotranspiration, should be developed based on site-specific water and nutrient uptake by the crops and ambient soil quality.

Journal information: Science of the Total Environment

Provided by Texas A&M University