Higgs search: A half-century odyssey

Over half a century, the Higgs boson has evolved from a theory rejected as daft to a cornerstone of our understanding of the Universe.

Conceived in 1964 to explain how matter acquired mass, the notion required the labour of thousands of scientists and billions of dollars worth of specialised equipment to graduate from theory to reality.

On July 4, 2012, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN) announced it had discovered a particle commensurate with the elusive boson—a breakthrough crowned Tuesday with the Nobel Prize in Physics.

"I had no idea it would happen in my lifetime," 84-year-old British physicist and Nobel co-laureate Peter Higgs said last year of the needle-in-a-haystack discovery bearing his name.

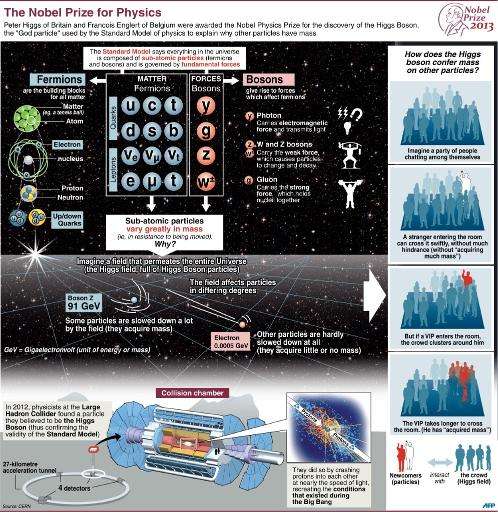

The Standard Model of physics, the most widely-accepted theory of how the known Universe works, is incomplete without the Higgs boson.

The boson explains how the building-brick fundamental particles that make up all matter acquired mass. The Standard Model dictates that the particles in themselves are massless.

Higgs bosons are believed to exist in a molasses-like, invisible field created in the first fractions of a second after the "Big Bang" 13.7 billion years ago.

Each boson is thought to act rather like a fork dipped in syrup and held up in dusty air. While some dust slips through cleanly, most becomes sticky—effectively acquiring mass. With mass comes gravity, which pulls particles together even as the Higgs bosons themselves decay into other particles.

An enthralling and sometimes disheartening quest for the omnipresent but elusive particle started with the publication in 1964 of three papers that predicted its existence.

First to publish were Francois Englert and Robert Brout of the Free University of Brussels, followed by Higgs and then the US-British team of Dick Hagen, Gerald Guralnik and Tom Kibble.

Higgs' first paper on the boson was rejected by Physics Letters, a journal then edited by the CERN—a decision the physicist said "shocked" him at the time.

He revised the paper and submitted it to a different journal, Physical Review Letters, which published it—making Higgs the flag bearer of a premise that many scientists helped to develop over the years.

"There was a lot of scepticism about whether this weird kind of field theory was going to work," Higgs said in a presentation to Kings College London in 2010.

After an address to Harvard in 1966, Higgs recalled, he was told by a colleague "they had been looking forward to tearing apart this idiot"—referring to himself.

But by the early 1970s, when the Standard Model was refined, the boson theory had gained much traction.

"Certainly, we had to wait before the theory itself was applied to something which is the Standard Model, which took some time," fellow Nobel recipient Englert said Tuesday.

"It took some time to prove the consistency of our theory. Only after that could one look for a test."

Higgs has described the search as "a very difficult task" and said: "In the beginning, people had no idea of where to look for it."

By 1989, particle-smashing experiments started at the CERN's Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP) near Geneva, searching in vain for clues of the Higgs' existence until it closed in 2000.

Exciting work was also carried out by the United States' own smasher at Fermilab in Illinois, which came agonisingly close to spotting the particle, but didn't have the raw colliding power to get the results.

The LEP was replaced by the Large Hadron Collider which started in 2008 and finally yielded the putative boson last year—"the final piece in the puzzle that is the Standard Model", according to Olga Botner, a member of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

"It has been a long journey but one that has inspired a generation to engage with the subject," said the president of Britain's Institute of Physics, Frances Saunders.

© 2013 AFP