Students' water-testing tool wins $40,000, launches nonprofit

University of Washington engineering students have won an international contest for their design to monitor water disinfection using the sun's rays. The students will share a $40,000 prize from the Rockefeller Foundation and are now working with nonprofits to turn their concept into a reality.

Team member Jacqueline Linnes, who recently completed her bioengineering doctorate, traveled to Bolivia last year with the UW chapter of Engineers Without Borders. While there, she and other students treated their drinking water by leaving it in plastic bottles in the sun.

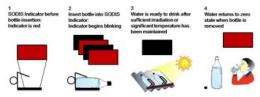

The concept is an old one. Solar disinfection of water in plastic bottles, also called SODIS, is promoted by many nonprofits. It offers a cheap and easy way to reduce some of the roughly 1.5 million diarrhea-related children's deaths each year. But global adoption has been slow, partly because it is hard to know when the water is safe to drink.

The UW entered a competition to design an indicator for Fundación SODIS, a Bolivia-based nonprofit dedicated to testing and promoting this method. Solar disinfection in water bottles removes more than 99.9 percent of bacteria and viruses, with results similar to chlorination.

The UW device lets users know when the sun's rays have done their job.

Linnes began working on the problem with Engineers Without Borders members Penny Huang, a senior in chemical engineering, and Chin Jung Cheng, then an undergraduate in chemical engineering and now a UW doctoral student in bioengineering.

At first, the students focused on developing a chemical test strip. Then they considered an electronic sensor and contacted Charlie Matlack, a UW doctoral student in electrical engineering.

Together they built a system using parts from a keychain that blinks in response to light.

"It has all the same components that you'd find inside a dirt-cheap solar calculator, except programmed differently," Matlack said.

Other electronics monitor how much light is passing through the bottle and whether a water-filled bottle is present, so the system knows when to stop or start recording data.

Winning the contest means the students split the $40,000 prize, and their efforts may improve the health of children around the world.

"This is part of what engineering education should be," said faculty adviser Howard Chizeck, an electrical engineering professor. "It's educating students with the skills and the desire to make things better."

The competition was put on by InnoCentive Inc., a Boston-based company that since 2001 has hosted a website where organizations can post technical challenges with prize money and anybody can submit a solution.

In this case, even the challenges themselves were solicited on the web. GlobalGiving Foundation Inc., a Washington, D.C. nonprofit that acts as a clearinghouse for charitable donations, asked nonprofits around the world to submit technical challenges relating to water quality. It then chose four to post to InnoCentive, and the Rockefeller Foundation supplied prize money.

The Sodis Foundation evaluated more than 70 proposals before choosing the UW's.

"The evaluators appreciated the fact that the [UW] device takes into consideration factors like the material of the bottle and the turbidity of the water to be disinfected," said co-director Matthias Saladin. "Other factors favoring the proposal were its robust design, the long product life and its competitive price."

The challenge called for designs costing less than $10. The UW students estimate their parts would retail for $3.40, and bulk buying could reduce the cost further.

The Sodis Foundation now holds a nonexclusive license to develop the technology. It is also focusing on larger-scale systems that could be used in situations such as disaster relief. A Sodis Foundation donor has also offered Matlack $16,000 to continue developing a prototype of the water bottle indicator. (The contest proposal tested each part of the system separately.)

Over the next few months Linnes, Matlack and Tyler Davis, a doctoral student in the UW Evans School of Public Affairs, are setting up a nonprofit business to manufacture and market the device, either to users or to nonprofits that promote solar disinfection.

They have approached UW faculty and local nonprofits as potential partners, hoping to draw on a broad range of expertise.

"We're at a point where we recognize the need for work on this beyond engineering," Matlack said. "Ultimately, the hardest part is going to be to get people to use it."

Provided by University of Washington