Lightning research links specific atmospheric conditions to exuberant, luminous displays above thunderstorms

A new study led by Florida Institute of Technology Professor Ningyu Liu has improved our understanding of a curious luminous phenomenon that happens 25 to 50 miles above thunderstorms.

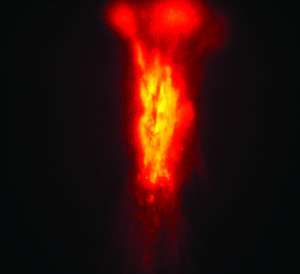

These spectacular phenomena, called sprites, are fireworks-like electrical discharges, sometimes preceded by halos of light, in earth's upper atmosphere. It has been long thought that atmospheric gravity waves play an important role in the initiation of sprites but no previous studies, until this team's recent findings, provided convincing arguments to support that idea.

The research, published in the June 29 issue of Nature Communications, includes comprehensive computer-simulation results from a novel sprite initiation model and dramatic images of a sprite event, and provides a clearer understanding of the atmospheric mechanisms that lead to sprite formation.

Understanding the conditions of sprite formation is important, in part, because they can interfere with or disrupt long-range communication signals by changing the electrical properties of the lower ionosphere.

Predicted by Nobel laureate C. T. R. Wilson in 1924 but not discovered until 1989, sprites are triggered by intense cloud-to-ground lightning strokes. They typically last a few to tens of milliseconds; they are bright enough to be seen with dark-adapted naked eyes at night; and only the most powerful lightning strokes can cause them.

The study, conducted by Liu, a Florida Tech professor of physics and space sciences, and collaborators Joseph Dwyer, a former professor at Florida Tech now at University of New Hampshire, Hans Stenbaek-Nielsen from University of Alaska Fairbanks, and Matthew McHarg from the United States Air Force Academy, investigated how sprites are initiated.

According to Liu, the perturbations in the upper atmosphere created by atmospheric gravity waves can grow in the electric field produced by lightning and eventually lead to sprites.

"Perturbations with small size and large amplitude are best for initiating sprites," Liu said. "If the size of the perturbation is too large, sprite initiation is impossible; if the magnitude of the perturbation is small, it requires a relatively long time for sprites to be initiated."

To validate their model, the team analyzed a sprite event captured simultaneously by high-speed, high-sensitivity cameras on two aircraft during an observation mission sponsored by the Japanese broadcasting corporation NHK. The high-speed images show that a relatively long-lasting sprite halo preceded the fast initiation of sprite elements, exactly as predicted by the model.

Hamid Rassoul, an atmospheric physicist and the dean of Florida Tech's College of Science, said the findings will be critical to future researchers.

"They will allow scientists to study not only sprites but also the mesospheric perturbations, which are difficult, if not impossible, to observe," he said.

Liu added, "Our findings also suggest that small, dim glows in the upper atmosphere may be frequently caused by intense lightning but elude the detection. There may be many interesting phenomena waiting for discovery with more sensitive imaging systems."

Publication details

Nature Communications: www.nature.com/ncomms/2015/150 … full/ncomms8540.html

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by Florida Institute of Technology