Existence of a group of 'quiet' quasars confirmed

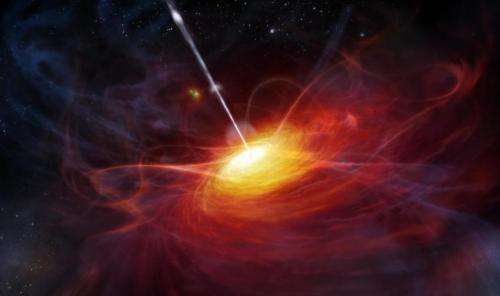

Aeons ago, the universe was different: mergers of galaxies were common and gigantic black holes with masses equivalent to billions of times that of the Sun formed in their nuclei. As they captured the surrounding gas, these black holes emitted energy. Known as quasars, these very distant and tremendously high energy objects have local relatives with much lower energy whose existence raises numerous questions: are there also such "quiet" quasars at much larger distances? Are the latter dying versions of the former or are they completely different?

Light from distant quasars takes billions of years to reach us, so when we detect it we are actually looking at the universe as it was a long time ago. "Astronomers have always wanted to compare past and present, but it has been almost impossible because at great distances we can only see the brightest objects and nearby such objects no longer exist", says Jack W. Sulentic, astronomer at the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia (IAA-CSIC), who is leading the research. "Until now we have compared very luminous distant quasars with weaker ones closeby, which is tantamount to comparing household light bulbs with the lights in a football stadium". Now we are able to detect the household light bulbs very far away in the distant past.

The more distant, the more luminous?

Quasars appear to evolve with distance: the farther away one gets, the brighter they are. This could indicate that quasars extinguish over time or it could be the result of a simple observational bias masking a different reality: that gigantic quasars evolving very quickly, most of them already extinct, coexist with a quiet population that evolves at a much slower rhythm but which our technological limitations do not yet allow us to research.

To solve this riddle it was necessary to look for low luminosity quasars at enormous distances and to compare their characteristics with those of nearby quasars of equal luminosity, something thus far almost impossible to do, because it requires observing objects about a hundreds of times weaker than those we are used to studying at those distances.

The tremendous light-gathering power of the GTC telescope, has recently enabled Sulentic and his team to obtain for the first time spectroscopic data from distant, low luminosity quasars similar to typical nearby ones. Data reliable enough to establish essential parameters such as chemical composition, mass of the central black hole or rate at which it absorbs matter.

"We have been able to confirm that, indeed, apart from the highly energetic and rapidly evolving quasars, there is another population that evolves slowly. This population of quasars appears to follow the quasar main sequence discovered by Sulentic and colleagues in 2000. There does not even seem to be a strong relation between this type of quasars, which we see in our environment and those "monsters" that started to glow more than ten billion years ago", says Ascensión del Olmo another IAA-CSIC researcher taking part in the study.

They have, nonetheless, found differences in this population of quiet quasars. "The local quasars present a higher proportion of heavy elements such as aluminium, iron or magnesium, than the distant relatives, which most likely reflects enrichment by the birth and death of successive generations of stars," says Jack W. Sulentic (IAA-CSIC). "This result is an excellent example of the new perspectives on the universe which the new 10 meter-class of telescopes such as GTC are yielding," the researcher concludes.

More information: J. W. Sulentic et al. "GTC Spectra of z ≈ 2.3 Quasars: Comparison with Local Luminosity Analogues". Astronomy & Astrophysics. DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201423975

Journal information: Astronomy & Astrophysics

Provided by Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia