Socially-assistive robots help kids with autism learn by providing personalized prompts

This week, a team of researchers from the USC Viterbi School of Engineering will share results from a pilot study on the effects of using humanoid robots to help children with autism practice imitation behavior in order to encourage their autonomy. Findings from the study, entitled "Graded Cueing Feedback in Robot-Mediated Imitation Practice for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders," will be presented at the 23rd IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) conference in Edinburgh, Scotland, on Aug. 27.

The pilot study was led by Maja Matarić, USC Viterbi Vice Dean for Research and the Chan Soon-Shiong Chair in Computer Science, Neuroscience and Pediatrics, whose research focuses on how robotics can help those with various special needs, including Alzheimer's patients and children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Her research team included doctoral student Jillian Greczek, postdoctoral researcher Amin Atrash, and undergraduate computer science student Edward Kaszubski.

"There is a vast health care need that can be aided by intelligent machines capable of helping people of all ages to be less lonely, to do rehabilitative exercises, and to learn social behaviors," said Matarić. "There's so much that can be done that can complement human care as well as other emerging technologies."

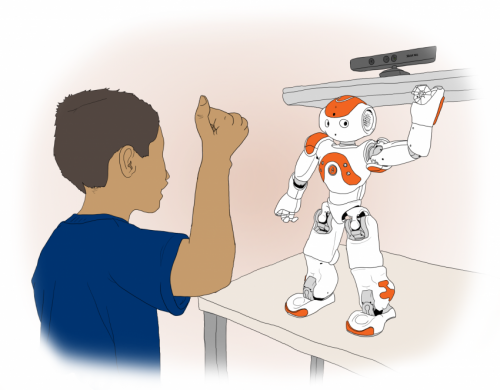

For the study, the researchers examined how children with ASD react to humanoid robots that provide graded cueing, an occupational therapy technique that shapes behavior by providing increasingly specific cues, or prompts, to help a person learn new or lost skills. Matarić and her team divided a group of 12 high-functioning children with ASD into two groups, one experimental and one control. Each child then played an imitation game ("copycat") with a Nao robot that asked the child to imitate 25 different arm poses.

"In this study we used graded cueing to develop the social skill of imitation through the copycat game," said Jillian Greczek, who oversaw the study. "Our hope is that learning such skills could be generalized. So, if a child with autism is at recess with friends, and some kids are playing Red Light/Green Light, the child might look at the game and say, 'Oh, I see how to play, and I can play with them too."'

When a child in either group imitated the pose correctly, the robot flashed its eyes green, nodded, or said "Good job!" When a child in the control group failed to imitate the pose correctly, the robot simply repeated the command without variation. However, for the experimental group participants, the Nao robot offered varied prompting when a child did not copy the pose accurately, at first providing only verbal cues and then following up with more detailed instructions and demonstrations of the pose.

The study showed that children who received the varied prompting (graded cueing feedback) until the correct action was achieved, showed improved or maintained performance, while children who did not receive graded cueing regressed or stayed the same. These results suggest that varied feedback was more effective and less frustrating to the study participants than merely receiving the same prompt repeatedly when they did not imitate the pose correctly. Furthermore it demonstrates that a socially assistive robot can be effective at providing such feedback.

Although this study did not exercise the graded cueing model to its fullest, the preliminary results show promise for the use of this technique to improve user autonomy through robot-mediated intervention. Matarić hopes that, within a decade, children with ASD might have their own personal robots to assist them with therapy, help prompt them through daily tasks, coach them through interactions with others, and encourage them to play with peers.

"The idea is to eventually give every child a personalized robot dedicated to providing motivation and praise and nudges toward more integration," Matarić said.

Provided by University of Southern California