Creation of entanglement simultaneously gives rise to a wormhole

Quantum entanglement is one of the more bizarre theories to come out of the study of quantum mechanics—so strange, in fact, that Albert Einstein famously referred to it as "spooky action at a distance."

Essentially, entanglement involves two particles, each occupying multiple states at once—a condition referred to as superposition. For example, both particles may simultaneously spin clockwise and counterclockwise. But neither has a definite state until one is measured, causing the other particle to instantly assume a corresponding state. The resulting correlations between the particles are preserved, even if they reside on opposite ends of the universe.

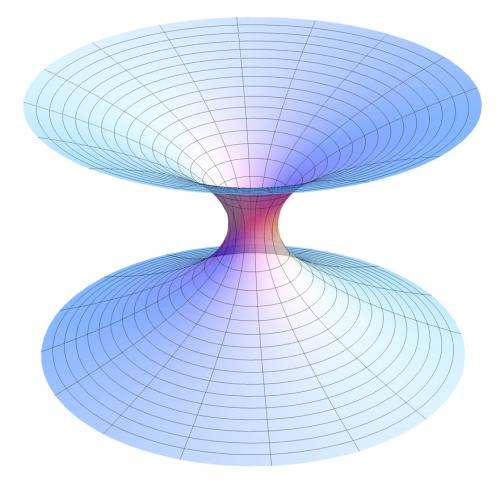

But what enables particles to communicate instantaneously—and seemingly faster than the speed of light—over such vast distances? Earlier this year, physicists proposed an answer in the form of "wormholes," or gravitational tunnels. The group showed that by creating two entangled black holes, then pulling them apart, they formed a wormhole—essentially a "shortcut" through the universe—connecting the distant black holes.

Now an MIT physicist has found that, looked at through the lens of string theory, the creation of two entangled quarks—the building blocks of matter—simultaneously gives rise to a wormhole connecting the pair.

The theoretical results bolster the relatively new and exciting idea that the laws of gravity holding together the universe may not be fundamental, but arise from something else: quantum entanglement.

Julian Sonner, a senior postdoc in MIT's Laboratory for Nuclear Science and Center for Theoretical Physics, has published his results in the journal Physical Review Letters, where it appears together with a related paper by Kristan Jensen of the University of Victoria and Andreas Karch of the University of Washington.

The tangled web that is gravity

Ever since quantum mechanics was first proposed more than a century ago, the main challenge for physicists in the field has been to explain gravity in quantum-mechanical terms. While quantum mechanics works extremely well in describing interactions at a microscopic level, it fails to explain gravity—a fundamental concept of relativity, a theory proposed by Einstein to describe the macroscopic world. Thus, there appears to be a major barrier to reconciling quantum mechanics and general relativity; for years, physicists have tried to come up with a theory of quantum gravity to marry the two fields.

"There are some hard questions of quantum gravity we still don't understand, and we've been banging our heads against these problems for a long time," Sonner says. "We need to find the right inroads to understanding these questions."

A theory of quantum gravity would suggest that classical gravity is not a fundamental concept, as Einstein first proposed, but rather emerges from a more basic, quantum-based phenomenon. In a macroscopic context, this would mean that the universe is shaped by something more fundamental than the forces of gravity.

This is where quantum entanglement could play a role. It might appear that the concept of entanglement—one of the most fundamental in quantum mechanics—is in direct conflict with general relativity: Two entangled particles, "communicating" across vast distances, would have to do so at speeds faster than that of light—a violation of the laws of physics, according to Einstein. It may therefore come as a surprise that using the concept of entanglement in order to build up space-time may be a major step toward reconciling the laws of quantum mechanics and general relativity.

Tunneling to the fifth dimension

In July, physicists Juan Maldacena of the Institute for Advanced Study and Leonard Susskind of Stanford University proposed a theoretical solution in the form of two entangled black holes. When the black holes were entangled, then pulled apart, the theorists found that what emerged was a wormhole—a tunnel through space-time that is thought to be held together by gravity. The idea seemed to suggest that, in the case of wormholes, gravity emerges from the more fundamental phenomenon of entangled black holes.

Following up on work by Jensen and Karch, Sonner has sought to tackle this idea at the level of quarks—subatomic building blocks of matter. To see what emerges from two entangled quarks, he first generated quarks using the Schwinger effect—a concept in quantum theory that enables one to create particles out of nothing. More precisely, the effect, also called "pair creation," allows two particles to emerge from a vacuum, or soup of transient particles. Under an electric field, one can, as Sonner puts it, "catch a pair of particles" before they disappear back into the vacuum. Once extracted, these particles are considered entangled.

Sonner mapped the entangled quarks onto a four-dimensional space, considered a representation of space-time. In contrast, gravity is thought to exist in the next dimension as, according to Einstein's laws, it acts to "bend" and shape space-time, thereby existing in the fifth dimension.

To see what geometry may emerge in the fifth dimension from entangled quarks in the fourth, Sonner employed holographic duality, a concept in string theory. While a hologram is a two-dimensional object, it contains all the information necessary to represent a three-dimensional view. Essentially, holographic duality is a way to derive a more complex dimension from the next lowest dimension.

Using holographic duality, Sonner derived the entangled quarks, and found that what emerged was a wormhole connecting the two, implying that the creation of quarks simultaneously creates a wormhole. More fundamentally, the results suggest that gravity may, in fact, emerge from entanglement. What's more, the geometry, or bending, of the universe as described by classical gravity, may be a consequence of entanglement, such as that between pairs of particles strung together by tunneling wormholes.

"It's the most basic representation yet that we have where entanglement gives rise to some sort of geometry," Sonner says. "What happens if some of this entanglement is lost, and what happens to the geometry? There are many roads that can be pursued, and in that sense, this work can turn out to be very helpful."

More information: Holographic Schwinger Effect and the Geometry of Entanglement, prl.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v111/i21/e211603

Journal information: Science , Physical Review Letters

Provided by Massachusetts Institute of Technology