Diamond imperfections pave the way to technology gold

(Phys.org) —From supersensitive detections of magnetic fields to quantum information processing, the key to a number of highly promising advanced technologies may lie in one of the most common defects in diamonds. Researchers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley have taken an important step towards unlocking this key with the first ever detailed look at critical ultrafast processes in these diamond defects.

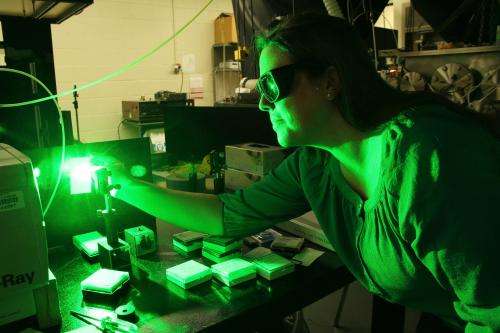

Using two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy on pico- and femto-second time-scales, a research team led by Graham Fleming, Vice Chancellor for Research at UC Berkeley and faculty scientist with Berkeley Lab's Physical Biosciences Division, has recorded unprecedented observations of energy moving through the atom-sized diamond impurities known as nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers. An NV center is created when two adjacent carbon atoms in a diamond crystal are replaced by a nitrogen atom and an empty gap.

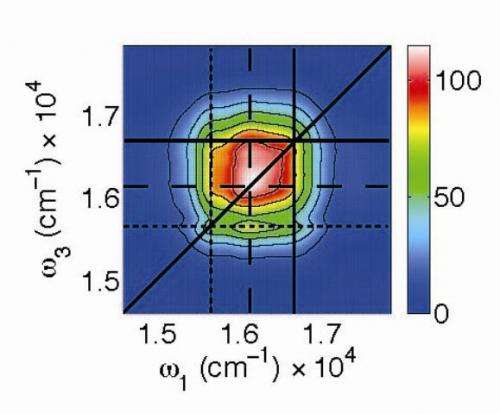

"Our use of 2D electronic spectroscopy allowed us to essentially map the flow of energy through the NV center in real time and observe critical quantum mechanical effects," Fleming says. "The results hold broad implications for magnetometry, quantum information, nanophotonics, sensing and ultrafast spectroscopy."

Fleming is the corresponding author of a paper in Nature Physics that describes this research entitled "Vibrational and electronic dynamics of nitrogen–vacancy centres in diamond revealed by two-dimensional ultrafast spectroscopy." The lead author is Vanessa Huxter, former member of Fleming's research group and now a professor at the University of Arizona. Other co-authors are Thomas Oliver and Dmitry Budker, both of whom holds joint appointments with Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley.

These 2D electronic spectroscopy measurements have provided us with the first window into the ultrafast dynamics of NV centers in diamond," says Huxter. "We were able to observe previously hidden vibrational and electronic properties of the NV center system, including the discovery of vibrational coherences lasting about two picoseconds, which on a quantum mechanical scale is a surprisingly long time."

Given the ubiquitous presence of weak magnetic fields, a sufficiently sensitive detector could be used in a wide range of applications including medical diagnostic and treatment procedures, chemical analyses, energy exploration and homeland security (to detect explosives). Diamond NV centers are held to be one of the finest magnetic sensors possible on the nanoscale. Diamond NV centers are also highly promising candidates for the creation of qubits – data encoded through quantum-spin rather than electrical charge that will be the heart and soul of quantum computing. Qubits can store exponentially more data and process it billions of times faster than classical computer bits. However, for these rich promises to be fully met, a much better fundamental understanding is needed of the electronic-state dynamics when an NV center is energized.

Says co-author Budker, a UC Berkeley physics professor with Berkeley Lab's Nuclear Sciences Division and leading authority on NV center physics, "NV centers in diamond are already becoming a workhorse in magnetometry and other sensor fields, but they remain somewhat of a black box in that we still don't know understand some important features of their energy levels and dynamics. Our findings in this study provide a starting point for new insights into such critical electronic-state phenomena as dephasing, spin addressing and relaxation."

This study was made possible by the unique 2D electronic spectroscopy technique, which was first developed by Fleming and his research group to study the quantum mechanical underpinnings of photosynthesis. This ultrafast technique enables researchers to track the transfer of energy between atoms or molecules that are coupled (connected) through their electronic and vibrational states. Tracking is done through both time and space. It is accomplished by sequentially flashing light from three laser beams on a sample while a fourth beam serves as a local oscillator to amplify and phase-match the resulting spectroscopic signals.

"By providing femtosecond temporal resolution and nanometer spatial resolution, 2D electronic spectroscopy allows us to simultaneously follow the dynamics of multiple electronic states," says Fleming, who has compared this technology to the early super-heterodyne radios.

In this new study, the use of 2D electronic spectroscopy revealed that the vibrational modes of NV centers in diamond – a subject of keen scientific interest because these modes directly affect optical and material properties – are strongly coupled to the defect.

"We were able to identify a number of individual vibrational modes and found that these modes were almost all local to the defect centers and that they were coherent - quantum mechanically coupled - for about two picoseconds," says Huxter. "Through a combination of theory and observation, researchers had suspected that NV center vibrational modes were primarily local to the defect, but our direct observation of the vibrations and their coupling to the excitation states confirms this idea."

In addition, the researchers also were able to measure non-radiative relaxation in the excited state, a property that must be understood and exploited for the creation of qubits.

"We found that the non-radiative relaxation timescale for NV centers in diamond was around four picoseconds, which was slower than we had expected given the number of vibrational states," Huxter says.

The information acquired from this study should make it possible to tune the properties of NV centers in diamonds and open up new avenues for research.

"For example, by optically pumping the NV centers we could specifically excite phonon modes based on their coupling factors," Fleming says. "This would allow the development of diamonds with NV centers that can be used for quantum storage and information processing based on both phonons and spin."

Journal information: Nature Physics

Provided by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory