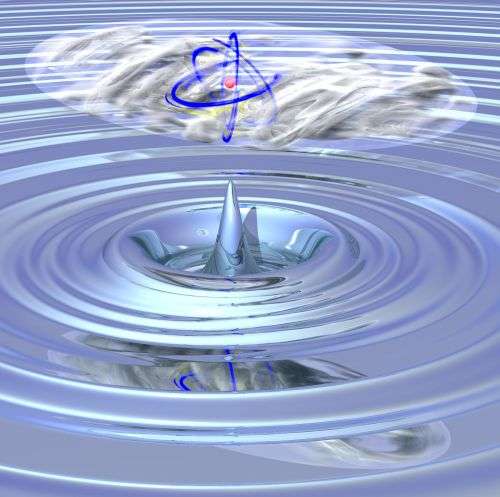

Giant atom eats quantum gas

A team of experimental and theoretical physicists from the University of Stuttgart studied a single micrometer sized atom. This atom contains tens of thousands of normal atoms in its electron orbital. These results have been published in the journal Nature.

The interaction of electrons and matter is fundamental to material properties such as electrical conductivity. Electrons are scattering from atoms of the surrounding matter and can excite lattice oscillations, so called phonons, thereby transferring energy to the environment. The electron is therefore slowed which causes electrical resistance. However, in certain materials phonons can surprisingly cause the opposite effect, so called superconductivity, where the electrical resistance drops to zero. Understanding the interaction of electrons and matter is therefore important goal in order to both answer fundamental questions as well as to solve technical problems.

A single electron is best suited for systematic investigations of such processes. For the first time, physicists from Stuttgart have now realized a model system in the laboratory, where the interaction of a single electron with many atoms inside its orbital can be studied. These atoms are from an ultracold cloud near absolute zero, a so called Bose-Einstein condensate.

The basic idea now is simple: Instead of using a technically challenging electron trap, the scientists are using the fact that in nature electrons are bound to a positively charged atomic core. In a classical picture, they are travelling on ellipsoidal orbits around the core. These orbits are usually very small, typically in the range below one nanometer. In order to achieve an interaction between an electron and many atoms, an atom is excited from a cloud consisting of 100.000 atoms using laser light. The orbit of a single electron then expands to several micrometers and a Rydberg atom is formed. On atomic length scales, this atom is huge, larger than most bacteria, which are consisting each of several billions to trillions of atoms. The Rydberg atom is then containing tens of thousands of atoms from the cold cloud. Thus, a situation is realized where the electron is trapped in a defined volume and at the same time interacts with a large number of atoms. This interaction is so strong that the whole atomic cloud, consisting of 100,000 atoms is considerably influenced by the single electron. Depending on its quantum state the electron excites phonons in the atomic cloud, which can be measured as collective oscillations of the whole cloud culminating in a loss of atoms from the trap.

The experimental observations in the group of Prof. Tilman Pfau could so far largely be explained by collaborative work with the theory group of Prof. Hans Peter Büchler. However, this work is only the basis for a series of further exciting experiments. According to the previous studies an electron is leaving a clear trace in the surrounding atomic cloud. Therefore imaging a single electron in a well defined quantum state seems to be feasible. Due to the impact on various fields, including quantum optics, these results were published in the highly respected journal Nature.

Publication details

Balewski, J. et al. Coupling a single electron to a Bose-Einstein condensate, Nature. DOI: 10.1038/nature12592

Journal information: Nature

Provided by University of Stuttgart