Breakthrough study models dying stars in a lab

A team of scientists has successfully reproduced conditions in one of the most hostile environments in the galaxy, enabling them to find out more about how atoms behave in these extreme settings.

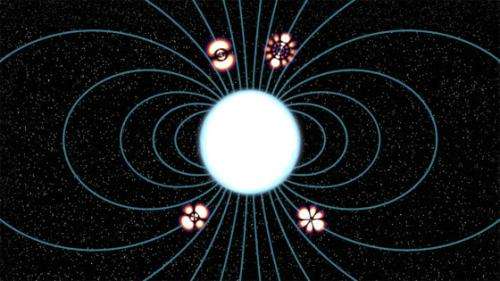

The study modelled conditions near to the surface of a white dwarf star – a stellar remnant comprising the dead embers which are left behind after Sun-like stars have exhausted their fuel. The environment is characterised by very high gravitational forces, very high temperatures, and occasionally very high magnetic fields.

These fields are astonishingly powerful, and thought to reach levels a billion times stronger than the Earth's. Matt Pang, who made the theoretical predictions which underpin the new study work, has described them as so strong that "if a fridge magnet with this strength was sitting in the Science Museum in central London, everyone with a pacemaker would have to move outside the M25."

More unpleasantly, chemistry around the surface of a white dwarf completely changes, and atoms that did not previously stick together can become bonded, while previously bonded molecules change their size and shape. Extreme environments like this are common in space, but often difficult, or impossible, to reproduce on Earth.

As a result, the new study marks a significant breakthrough in using readily-available materials to model astrophysical phenomena. The team, led by the University of Surrey, discovered that ordinary silicon crystals of the same type used to make computer chips are so sensitive to the effects of a much weaker magnetic field in a laboratory that they could achieve the same conditions as the strongest magnetic white dwarfs.

The researchers doped phosphorous into silicon, which can be scaled with relative ease to compare its atomic properties with those of hydrogen. They then compared the spectrum of phosphorous patterns under laboratory magnetic fields with those obtained for hydrogen on white dwarf stars.

The results showed that in these conditions, the electron cloud around a hydrogen atom was changed to a variety of patterns, ranging from fans, to shapes resembling highly-elongated, and slightly lumpy, pencils.

Professor Paul Murdin, from the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge, one of the co-authors of the work, said: "The theory predicting the behaviour of hydrogen atoms in magnetic fields this high has been around for just under a century, but until now, no-one was able to test it right up at the limit seen on white dwarfs. We are looking forward to using the principle to see what happens to molecules, where the theory is almost impossibly hard."

The team is now looking for this same effect on other more complicated atoms and molecules in white dwarfs .

Ellis Bowyer, a doctoral researcher from Surrey who did the experiments, said: "It's not just about astronomy – there are also practical implications. Learning how to control the shapes of tiny electron clouds in silicon chips is letting us design new kinds of computer chips, called quantum computers, where the transistors contain just one atom."

More information: Nature Communications: dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2466

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by University of Cambridge