Amazon's flying water vapor rivers bring rain to Brazil

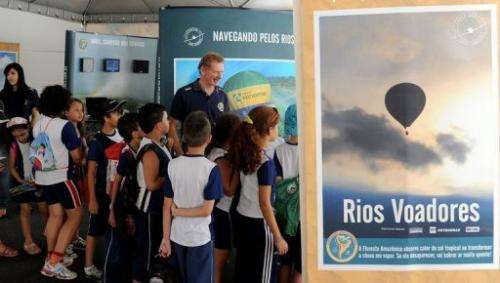

As devastating drought spreads across much of the globe, British-born pilot Gerard Moss flies above the Amazon rainforest to show how its "flying rivers"—humid air currents—bring rain to Brazil and South America.

Aboard his single-engine Embraer 721 aircraft, Moss, a naturalized Brazilian, was on a 45-minute flight from Brasilia to Goiania, capital of the central state of Goias.

"Climate change is taking its toll. The United States is going through its worst drought in half a century, Russia is also reeling from drought and in India monsoon rains have for years been irregular," he told AFP.

"Brazil is less affected because we have the world's biggest tropical forest, which helps regulate the climate."

Deforestation is also a factor. With logging and agriculture shrinking Brazil's rainforests, there are fewer trees to release the water vapor that creates these flying rivers.

The flying rivers travel from the Amazon toward the Andes, which act as a natural barrier and redirect huge vapor masses toward the center-west, southeast and south of Brazil as well as to the north of Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, French Guiana and Suriname.

"Peru also receives some of that water, but were it not for the Cordillera, it would surely receive it all," Moss said.

During the Goiania-bound flight, Moss monitored an indicator that measures air humidity and helps locate the flying rivers.

"Very few people realize that apart from CO2 capturing, a single tree is capable of sending in the atmosphere more than 1,000 liters a day," he said.

"The entire Amazon basin is a supplier of fresh water for many other parts of Brazil and the northern parts of Argentina, so it is important for the climate and economy of Brazil," he added.

He has spent five years trying to spread the message that the Amazon rainforest not only cleans the planet's air but also guarantees humidity and rain in Brazil and part of South America, a huge food producing and exporting region.

Moss, who grew up in Switzerland, arrived in Brazil in the 1980's to work on soybean exports. A decade later, he changed course and decided to devote himself to the environment along with his Kenyan-born wife.

In 2003, they launched their first project to protect Brazil's waters, which provide 12 percent of the planet's fresh water supply. For one year they flew a small seaplane to collect more than 1,000 samples from the country's most remote rivers and lakes.

"We noticed that 85 percent of the water is clean, which shows that Brazil has a great wealth, but also that in inhabited areas, the water quality is poor," he said.

He once flew eight days above a flying river from the Amazon city of Belem to Pantanal, in the center-west, and Sao Paulo in the south.

"It was a huge mass of water vapor equivalent to what Sao Paulo consumes in 115 days. It was great to publicize our results," he said.

With these results, the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) does daily tracking of Amazon humidity currents across the whole of Brazil.

Moss is now busy publicizing the results to further his goal of saving the Amazon.

"The Amazon for many people, for a taxi driver in Sao Paulo, is very far, far away, something that makes no difference. And we want to show that it does make a difference," he told AFP.

"When we lose certain areas of the Amazon through land expansion, maybe cattle, maybe soybean, we have to realize that we are losing ecoservices that will cost us dearly in the future," he said with passion.

"It is a question of trying to change the mentality of the people, we want to save the Amazon basin, we want to save every single tree there."

Scientists believe nearly 20 percent of the Amazon has been destroyed and some fear a point of no return if destruction reaches 35 to 40 percent.

Large-scale deforestation has made Brazil one of the world's top greenhouse gas emitters, but the government has vowed to curb it and has made significant strides in the past decade.

Brazilian authorities confirmed earlier this year that deforestation fell to a record low of 6,418 square kilometers (2,478 square miles) in 2011, down from a peak of 27,000 square kilometers (10,000 square miles) in 2004.

(c) 2012 AFP