This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

proofread

Study shows naming farm animals reduces preschoolers' desire to eat them

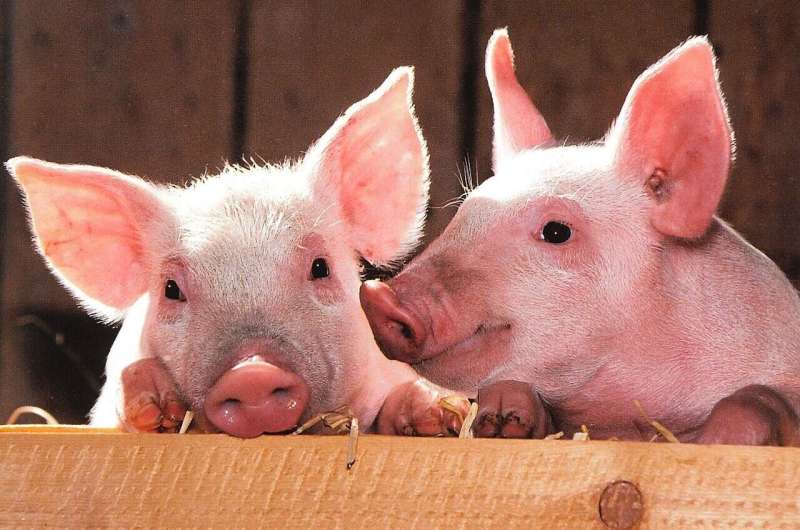

Giving a chicken, turkey or pig a name and pointing out its individual qualities may change children's attitudes towards animals. It makes children perceive animals as more similar to humans. They will prefer to befriend the animals rather than eat them, say researchers from SWPS University.

Animals in children's shows and stories are frequently depicted with specific names, unique characteristics, and personal preferences. A good example is the popular show Peppa Pig.

Does assigning individual characteristics to animals encourage children to humanize them and relate to them, discouraging children from consuming meat? According to some researchers, this is not necessarily the case, because consumers often disregard the fact that the meat on their plate comes from real animals. Young children, on the other hand, may simply not know this yet.

Does the cutlet come from a pig?

The recognition that meat consumption causes harm to animals evokes cognitive dissonance because people generally like animals and want to care for them. To alleviate this discomfort without abandoning their existing eating habits, people often employ various defense strategies.

For example, people may reject the idea that edible animals share human-like mental attributes, such as the capacity to experience suffering. Consequently, the more meat products people consume, the less they perceive edible animals as similar to humans and the less empathy they tend to show towards them, says Dr. Aleksandra Rabinovitch from the Faculty of Psychology in Sopot, SWPS University.

She adds that before children understand where meat comes from, they are considered to be unaware consumers. They like animals that look "nice" and think of them as they think of other people, in terms of bonding. Small children certainly do not associate animals with food.

Foreign research showed that although the majority of American children aged 4–7 years considered pig (73.3%) and chicken (65.9%) as "not OK to eat," approximately 30% of these children were incorrect in determining the origin of animal-based products.

So far, there has been no research that would directly investigate the impact of individualizing animals on attributing human characteristics to them and reducing the acceptance of eating meat. There were no analyses that would verify such a trend among children.

Researchers from the Social Behavior Research Center at SWPS University examined this issue and published the results in the journal Appetite.

How do children perceive animals?

A total of 208 preschool children aged 5–6 years took part in two studies and were presented with pictures of pigs and chickens. At the beginning of the study, the children were asked whether they knew where meat came from. Most children (over 72%) responded correctly, indicating either animals in general, or specific animals, as a source of meat. They were also asked how much they enjoyed eating meat.

Then, some children were shown a photo with a pig that was given a name, personal habits and preferences: "This is Lelka, the only pig of her kind in the world. Lelka's favorite food is warm potatoes. Lelka enjoys running in the field, digging in the ground, and splashing around in the mud."

The remaining children heard a description that referred to pigs as a group. In the last part of the study, children assessed their willingness to make friends with an animal and their willingness to eat its meat.

A similar procedure was used in the second study. In this case, however, the object of the preschoolers' analysis were chickens. Additionally, the children were also asked to rate how similar the chicken was to humans, for example, whether it had the capacity to experience emotions.

Significantly more children who were presented with a pig that had a name and habits found it unique (79%) compared to children who were presented with an animal without individual characteristics (21%). Preschoolers from the first group much more often declared the desire to befriend such an animal, and much less often the desire to eat dishes made with its meat.

The situation was similar in the study with chickens. Significantly more children (over 84%) found the chicken unique when it was given a name, compared to preschoolers who perceived chickens in general as a species (just over 9%). Moreover, the children from the first group perceived the chicken as more human-like. They were also much more willing to make friends with the chicken and less willing to use it for meat.

The results of these two studies indicate that in children, identifying an edible animal with a name and personal characteristics that emphasize the animal's uniqueness is a powerful tool that can alter attitudes towards it. This pattern of results confirms that identifying information is what makes a difference in decreasing children's intention to consume an animal, regardless of whether the animal is a pig or a chicken, comments Dr. Rabinovitch.

More information: Aleksandra Rabinovitch et al, Eating pigs, not Peppa Pig: The effect of identifiability on children's propensity to humanize, befriend, and consume edible animals, Appetite (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.appet.2024.107505

Journal information: Appetite

Provided by SWPS University