This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

NASA tool prepares to image faraway planets

The Roman Coronagraph Instrument on NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will help pave the way in the search for habitable worlds outside our solar system by testing new tools that block starlight, revealing planets hidden by the glare of their parent stars. The technology demonstration recently shipped from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California to the agency's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, where it has joined the rest of the space observatory in preparation for launch by May 2027.

Before its cross-country journey, the Roman Coronagraph underwent the most complete test of its starlight-blocking abilities yet—what engineers call "digging the dark hole." In space, this process will enable astronomers to observe light directly from planets around other stars, or exoplanets. Once demonstrated on Roman, similar technologies on a future mission could enable astronomers to use that light to identify chemicals in an exoplanet's atmosphere, including ones that potentially indicate the presence of life.

Let the testing begin

For the dark hole test, the team placed the coronagraph in a sealed chamber designed to simulate the cold, dark vacuum of space. Using lasers and special optics, they replicated the light from a star as it would look when observed by the Roman telescope. When the light reaches the coronagraph, the instrument uses small circular obscurations called masks to effectively block out the star, like a car visor blocking the sun or the moon blocking the sun during a total solar eclipse. This makes fainter objects near the star easier to see.

Coronagraphs with masks are already flying in space, but they can't detect an Earth-like exoplanet. From another star system, our home planet would appear approximately 10 billion times dimmer than the sun, and the two are relatively close to one another. So trying to directly image Earth would be like trying to see a speck of bioluminescent algae next to a lighthouse from 3,000 miles (about 5,000 kilometers) away. With previous coronagraphic technologies, even a masked star's glare overwhelms an Earth-like planet.

The Roman Coronagraph will demonstrate techniques that can remove more unwanted starlight than past space coronagraphs by using several movable components. These moving parts will make it the first "active" coronagraph to fly in space. Its main tools are two deformable mirrors, each only 2 inches (5 centimeters) in diameter and backed by more than 2,000 tiny pistons that move up and down. The pistons work together to change the shape of the deformable mirrors so that they can compensate for the unwanted stray light that spills around the edges of the masks.

The deformable mirrors also help correct for imperfections in the Roman telescope's other optics. Although they are too small to affect Roman's other highly precise measurements, the imperfections can send stray starlight into the dark hole. Precise changes made to each deformable mirror's shape, imperceptible to the naked eye, compensate for these imperfections.

"The flaws are so small and have such a minor effect that we had to do over 100 iterations to get it right," said Feng Zhao, deputy project manager for the Roman Coronagraph at JPL. "It's kind of like when you go to see an optometrist and they put different lenses up and ask you, 'Is this one better? How about this one?' And the coronagraph performed even better than we'd hoped."

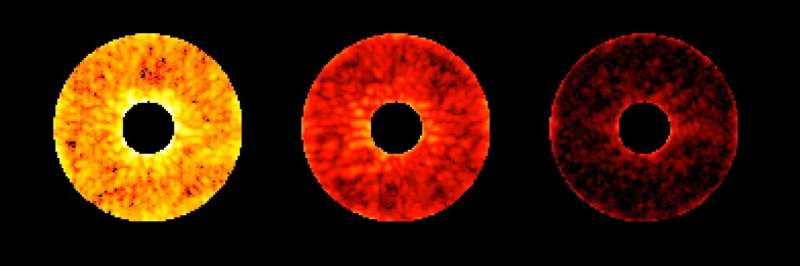

During the test, the readouts from the coronagraph's camera show a doughnut-shaped region around the central star that slowly gets darker as the team directs more starlight away from it—hence the nickname "digging the dark hole." In space, an exoplanet lurking in this dark region would slowly appear as the instrument does its work with its deformable mirrors.

Habitable worlds

More than 5,000 planets have been discovered and confirmed around other stars in the last 30 years, but most have been detected indirectly, meaning their presence is inferred based on how they affect their parent star. Detecting these relative changes in the parent star is far easier than seeing the signal of the much fainter planet. In fact, fewer than 70 exoplanets have been directly imaged.

The planets that have been directly imaged to date aren't like Earth: Most are much bigger, hotter, and typically farther from their stars. These features make them easier to detect but also less hospitable to life as we know it.

To look for potentially habitable worlds, scientists need to image planets that are not only billions of times dimmer than their stars, but also orbit them at the right distance for liquid water to exist on the planet's surface—a precursor for the kind of life found on Earth.

Developing the capabilities to directly image Earth-like planets will require intermediate steps like the Roman Coronagraph. At its maximum capability, it could image an exoplanet similar to Jupiter around a star like our sun: a large, cool planet just outside the star's habitable zone.

What NASA learns from the Roman Coronagraph will help blaze a path for future missions designed to directly image Earth-size planets orbiting in the habitable zones of sun-like stars. The agency's concept for a future telescope called the Habitable Worlds Observatory aims to image at least 25 planets similar to Earth using an instrument that will build on what the Roman Coronagraph Instrument demonstrates in space.

"The active components, like deformable mirrors, are essential if you want to achieve the goals of a mission like the Habitable Worlds Observatory," said JPL's Ilya Poberezhskiy, the project systems engineer for the Roman Coronagraph. "The active nature of the Roman Coronagraph Instrument allows you to take ordinary optics to a different level. It makes the whole system more complex, but we couldn't do these incredible things without it."

Provided by NASA