This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

What four decades of canned salmon reveal about marine food webs

Alaskan waters are a critical fishery for salmon. Complex marine food webs underlie and sustain this fishery, and scientists want to know how climate change is reshaping them. But finding samples from the past isn't easy.

"We have to really open our minds and get creative about what can act as an ecological data source," said Natalie Mastick, currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University.

As a doctoral student at the University of Washington in Seattle, Mastick investigated Alaskan marine food webs using a decidedly unorthodox source: old cans of salmon. The cans contained filets from four salmon species, all caught over a 42-year period in the Gulf of Alaska and Bristol Bay. Mastick and her colleagues dissected the preserved filets from 178 cans and counted the number of anisakid roundworms—a common, tiny marine parasite—within the flesh.

The parasites had been killed during the canning process, and if eaten, would have posed no danger to a human consumer. But counting anisakids is one way to gauge how well a marine ecosystem is doing.

"Everyone assumes that worms in your salmon is a sign that things have gone awry," said Chelsea Wood, a UW associate professor of aquatic and fishery sciences. "But the anisakid life cycle integrates many components of the food web. I see their presence as a signal that the fish on your plate came from a healthy ecosystem."

The research team reports in a paper published April 4 in Ecology & Evolution that anisakid worm levels rose for chum and pink salmon from 1979 to 2021, and stayed the same for coho and sockeye salmon.

-

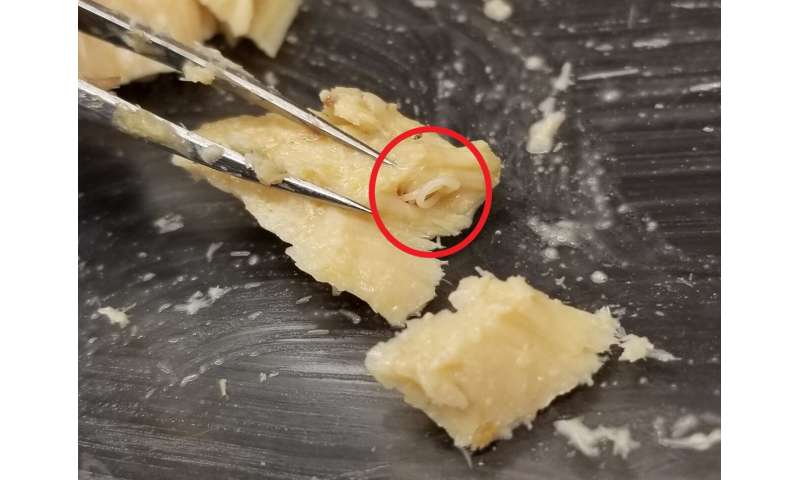

A highly degraded anisakid parasite recovered from canned salmon. Scale bar is 0.5 millimeters. Credit: Natalie Mastick/University of Washington -

A photo of an anisakid worm—circled in red—in a canned salmon filet. Credit: Natalie Mastick/University of Washington

"Anisakids have a complex life cycle that requires many types of hosts," said Mastick, who is lead author on the paper. "Seeing their numbers rise over time, as we did with pink and chum salmon, indicates that these parasites were able to find all the right hosts and reproduce. That could indicate a stable or recovering ecosystem, with enough of the right hosts for anisakids."

Anisakids start out living freely in the ocean. They enter food webs when eaten by small marine invertebrates, such as krill. As that initial host gets eaten by another species, the worms come along for the ride. Infected krill, for example, could be eaten by a small fish, which in turn gets eaten by a larger fish, like salmon. This cycle continues until the anisakids end up in the intestine of a marine mammal, where they reproduce. The eggs are excreted back into the ocean to hatch and begin the cycle again with a new generation.

"If a host is not present—marine mammals, for example—anisakids can't complete their life cycle and their numbers will drop," said Wood, who is senior author on the paper.

People cannot serve as hosts for anisakids. Consuming them in fully cooked fish poses little danger, because the worms are dead. But anisakids—also known as "sushi worms" or "sushi parasites"—can cause symptoms similar to food poisoning or a rare condition called anisakiasis if ingested alive in raw or undercooked fish.

The Seafood Products Association, a Seattle-based trade group, donated the cans of salmon to Wood and her team. The association no longer needed the cans, which had been set aside each year for quality control purposes. Mastick and co-author Rachel Welicky, an assistant professor at Neumann University in Pennsylvania, experimented with different methods to dissect the canned filets and look for anisakids. The worms are about a centimeter (0.4 inches) long and tend to coil up in the fish muscle. They found that pulling the filets apart with forceps allowed the team to count worm corpses accurately with the aid of a dissecting microscope.

There are several explanations for the rise of anisakid levels in pink and chum salmon. In 1972, Congress passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which has allowed populations of seals, sea lions, orcas and other marine mammals to recover following years of decline.

"Anisakids can only reproduce in the intestines of a marine mammal, so this could be a sign that over our study period—from 1979 to 2021—anisakid levels were rising because of more opportunities to reproduce," said Mastick.

Other possible explanations include warming temperatures or positive impacts of the Clean Water Act, Mastick added.

The stable anisakid levels in coho and sockeye are harder to interpret because there are dozens of anisakid species, each with their own series of invertebrate, fish and mammal hosts. While the canning process left the tough anisakid exterior intact, it destroyed the softer parts of their anatomy that would have allowed identification of individual species.

Mastick and Wood believe this approach could be used to look at parasite levels in other canned fish, like sardines. They also hope this project will help make new, serendipitous connections that could fuel additional insight into ecosystems of the past.

"This study came about because people heard about our research through the grapevine," said Wood. "We can only get these insights into ecosystems of the past by networking and making the connections to discover untapped sources of historical data."

Co-authors on the paper are UW undergraduate Aspen Katla, and Bruce Odegaard and Virginia Ng with the Seafood Products Association.

More information: Natalie Mastick et al, Opening a can of worms: Archived canned fish fillets reveal 40 years of change in parasite burden for four Alaskan salmon species, Ecology and Evolution (2024). DOI: 10.1002/ece3.11043

Journal information: Ecology and Evolution

Provided by University of Washington