This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Researchers disprove current thinking on how to achieve global collaboration

The world's most pressing issues such as climate change will only be solved through global cooperation. New research by academics at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, however, has identified a fundamental flaw in the theory that underpins much of today's thinking around how to create the lasting and meaningful large-scale change needed to solve these issues.

Current thinking is based on a seminal model by Panchanathan and Boyd published in Nature in 2004, which found that having a reputation for caring about issues such as climate change improved the likelihood that people would want to cooperate with you.

This is the theory behind "virtual signaling," and it is on the basis of this model that many interventions and experiments have been designed by organizations working to solve these problems.

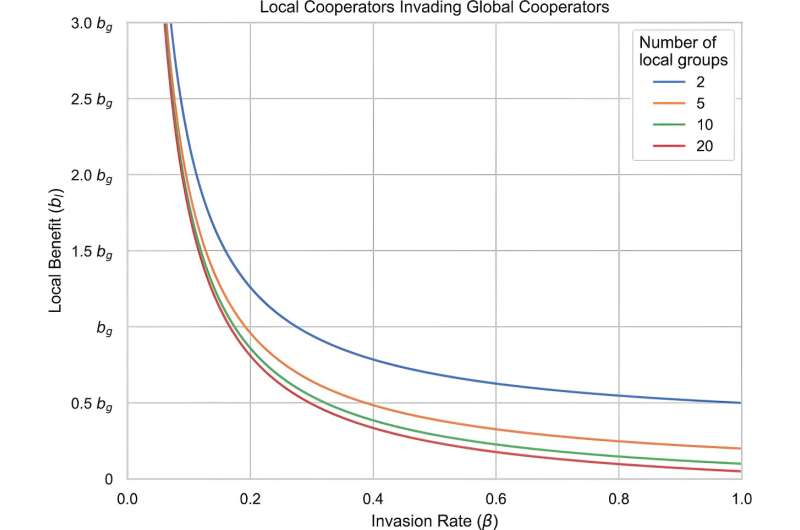

The finding by Eric Schnell and Professor Michael Muthukrishna, however, identifies a flaw in this model, showing that while reputation is important at a local level (i.e., being a good friend or colleague), being known for acting virtuously (i.e., how sustainable one's operations are) is not enough to generate the collaborations needed at a global level to tackle problems such as climate change.

This is because, the paper explains, the earlier model assumes that people have just one reputation. Reputation, however, is not a singular issue—for example, one can be known for being excellent at recycling but mediocre at office administration.

Schnell and Muthukrishna's new model explores what impact multiple reputations can have on people's decision-making processes. They find that, when local and global issues are both in play, people will always favor the local benefit someone can bring to them specifically over someone doing a good deed that has less of a tangible benefit.

The modeling also shows that this is felt more keenly during hard times. When a society is successful, people can afford to care more about the more global issues, however, during a cost of living crisis the immediate benefits one can gain from a local collaboration will far outweigh the less direct benefits (i.e., during times of economic hardship, people care more about immediate benefits from others, than if others care about the environment).

Dr. Muthukrishna, Department of Psychological and Behavioral Science at LSE, said, "Our model shows that reputation alone is not enough to generate large-scale cooperation and that people care far more about immediate rewards (e.g., are you a good friend, colleague, or project partner) than whether someone has acted virtuously (e.g., are you trying to eat more sustainably)."

Schnell, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Psychological and Behavioral Science at LSE, said, "Reputation has long been considered a key way to encourage collaboration at all levels—from individuals to organizations or between nations.

"Our finding, however, helps explain why global leaders, policymakers and campaigning organizations have, to date, failed to generate the kind of global cooperation needed to bring about major societal improvements the world is grappling with."

More information: Eric Schnell et al, Indirect reciprocity undermines indirect reciprocity destabilizing large-scale cooperation, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2322072121

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , Nature

Provided by London School of Economics