This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

An infectious gibbon ape leukemia virus found to be colonizing a rodent's genome in New Guinea

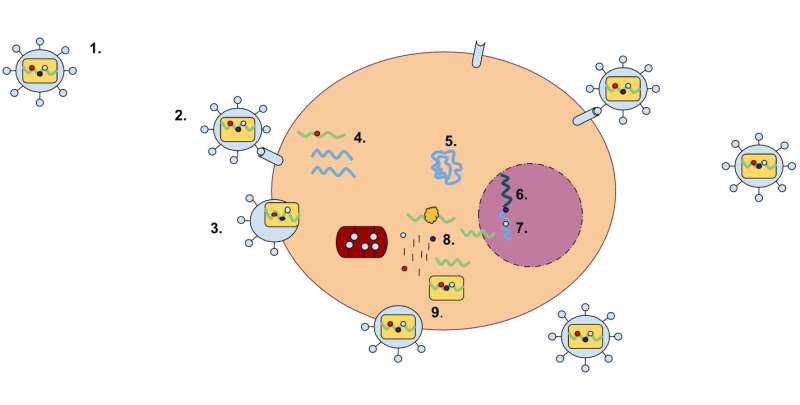

A research team has caught a glimpse of a rare case of retrovirus integration. Retroviruses are viruses that multiply by incorporating their genes into the genome of a host cell. If the infected cell is a germ cell, the retrovirus can then be passed on to the next generation as an "endogenous" retrovirus (ERV) and spread as part of the host genome in that host species.

In vertebrates, ERVs are ubiquitous and sometimes make up 10% of the host genome. However, most retrovirus integrations are very old, already degraded and therefore inactive—their initial impact on host health has been minimized by millions of years of evolution.

A research team led by the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) has now discovered a recent case of retrovirus colonization in a rodent from New Guinea, the white-bellied mosaic-tailed rat.

In a paper in the journal "Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences," they describe this new model of virus integration. The observations on this process will help to improve our understanding how retroviruses rewrite host genomes.

Retroviruses, such as the pathogen responsible for AIDS (HIV-1), integrate into the genome of the host cells they infect during their life cycle. When this happens in the germline (egg cells or cells that produce sperm) of the host, the retrovirus can actually become a gene of the host itself.

This process is apparently common, as up to 10% of the genomes of most vertebrates consist of the remnants of such ancient infections. One of the best-studied models of this process is the koala retrovirus (KoRV), which is currently colonizing the koala genome.

"What happens to the virus and the host during this process of genome colonization we do not know, as most such events occurred millions of years ago and we only see the leftover 'fossils' of the retrovirus," says Prof Alex Greenwood, head of the Leibniz-IZW Department of Wildlife Diseases.

"Nor do we know what the host suffered health-wise during the infection process. The koala retrovirus (KoRV) is one of the few models of this process that occurs in real time and where we can observe the effects of genome colonization on the host animal."

There is now some evidence that KoRV-related viruses are circulating in rodents and bats in Papua New Guinea and Indonesia.

A group led by Greenwood and Dr. Saba Mottaghinia, former Ph.D. student in Greenwood's department, analyzed 278 samples from seven bat and one rodent family endemic to the Australo-Papua region (Australia and New Guinea). They discovered a retrovirus that is currently colonizing the genome of an endemic rodent from New Guinea, the white-bellied mosaic-tailed rat (Melomys leucogaster). This is only the second example from the Australo-Papuan region, after KoRV, of a retrovirus that has colonized a genome while retaining a functional viral life cycle.

The gibbon ape leukemia viruses (GALV), a group of viruses discovered in gibbons and wooly monkeys at a research facility in Thailand in the 1960s, are very closely related to KoRV. This is a curious and surprising relationship, as there is a geographical barrier, known as the Wallace lineage, which separates the fauna of Southeast Asia from Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Australia's fauna.

However, there is evidence that the gibbons and wooly monkeys at the research facility in Thailand have been infected with viruses from Papua New Guinea. "The discovery of GALV-like viruses in rodents and bats in Indonesian and Australian rodents and bats from New Guinea suggests that these viruses, and possibly also KoRV, originated in New Guinea," says Greenwood, who initiated the research project.

The Leibniz-IZW team, together with scientists from the Charité, the Robert Koch Institute, the Max Delbrück Center, the University of Nicosia, California State University Fullerton, the South Australian Museum and Museum Victoria, examined 278 bat and rodent samples from Australia and New Guinea for KoRV and GALV-like viruses.

They detected a GALV, the Wooly Monkey Virus (WMV) in a population of the white-bellied mosaic-tailed rat, an endemic rodent from New Guinea. In five of the rats from two New Guinea collection sites, WMV was integrated into the genome at the same location, indicating that it has spread as a gene and not by infection, i.e. it has become part of the genome. However, in other white-bellied mosaic-tailed rat populations the virus was absent—similar to KoRV in koalas, where all koalas in northern Australia have KoRV in their genome, whereas there are koalas in southern Australia that do not have intact KoRV.

The virus, now called the "complete Melomys wooly monkey virus" (cMWMV), was able to infect cell lines, produce new viral progeny, was visible by electron microscopy as viral particles that detached from the cell membrane, and was even sensitive to the antiretroviral drug AZT.

"The virus has all the characteristics of an exogenous infectious retrovirus, but is endogenous. It is probably a very recent colonization event, much younger than KoRV," says Dr. Saba Mottaghinia, the lead author of the paper.

The results suggest that cMWMV is a new model for retroviral colonization of the host genome that occurs in real time, as in KoRV, and they also suggest that GALVs like WMV originated in the diverse fauna of New Guinea. The discoveries in New Guinea have certainly not been exhausted.

"There are hundreds of mammalian species from this region that have not yet been studied, suggesting that many more viruses and models exist in this region," says Greenwood.

More information: Mottaghinia S, et al, A Recent Gibbon Ape Leukemia Virus Germline Integration in a Rodent from New Guinea. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024) DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2220392121. www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2220392121

Provided by The Leibniz Association