This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

written by researcher(s)

proofread

Researchers: 'Nature positive' isn't just planting a few trees, it's actually stopping the damage we do

Have you heard the phrase "nature positive?" It's suddenly everywhere.

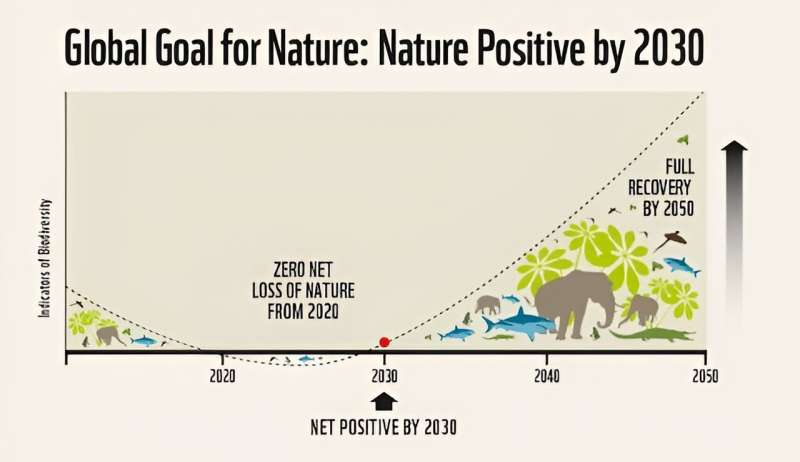

The idea is simple: rather than continually erode the natural world, nature positive envisions a future with more nature than we have now.

Created by an environmental alliance, the nature positive concept has been embraced by industry, world leaders and conservationists.

Sudden popularity can be reason for caution. After all, we've seen well-intended ideas become cover for greenwashing before. And without strong guardrails, we risk nature positive being used as a distraction from continued failures.

Our new research points to three ways to make sure nature positive is truly positive for nature.

What's the big idea?

According to the Nature Positive Initiative, "nature positive" aims to "halt and reverse nature loss measured from a baseline of 2020, through increasing the health, abundance, diversity and resilience of species, populations and ecosystems so that by 2030 nature is visibly and measurably on the path of recovery."

So, nature positive means seriously scaling back negative impacts on nature—through tackling land clearing, invasive species, and climate change—while also investing in positive impacts like ecosystem restoration and rewilding.

The goal is hugely ambitious. But it's also essential.

The natural world is humanity's life-support system. But we have now seriously compromised the biosphere's ability to support us.

Australia's environment minister, Tanya Plibersek, has backed the idea, announcing plans for a nature positive summit next year. The goal: "drive private sector investment to protect and repair our environment."

You can also see the influence of nature positive in Plibersek's plans for a nature repair market. And just this month, the New South Wales review of biodiversity laws recommended nature positive become "mandatory."

We must be wary of greenwashing

The risk of big-picture plans is that they can be used for PR purposes—serving to make companies or governments look good on the environment rather than actually improving nature's lot.

Already, the term nature positive is being used too freely to refer to any vaguely green action.

This new focus on nature positive mustn't distract from the need to fully address ongoing negative impacts.

Take the Australian government's Nature Positive Plan—its official response to the scathing 2020 review of Australia's national environment law.

Under the plan, "conservation payments" could be made by developers when destruction of threatened biodiversity is permitted, but suitable environmental offsets cannot be found.

These conservation payments would then be invested by government into conservation projects—but they would not necessarily benefit the same biodiversity destroyed by the development.

The plan states this approach will deliver "better overall environmental outcomes." In reality it could make it possible to destroy habitat of our most threatened species and replace it with other, easier-to-replace biodiversity—as long as there is more "nature" overall.

Positive for nature: The fundamentals

For "nature positive" to actually be positive for nature, it must do what it says on the tin. We cannot let this vitally important movement be used to justify further loss of valuable ecosystems or species, or to exaggerate the benefits of action.

Our research suggests three ways to make sure claims about nature positive are not misleading.

First, we have to make sure any proposal that might damage nature follows the "mitigation hierarchy." In short: can biodiversity losses be avoided entirely? If not, can they be kept to a bare minimum? Any remaining impacts must be fully compensated with gains of the same type and amount elsewhere.

Unfortunately, this is rarely achieved. In practice, developers often do poorly on avoiding or minimizing damage. Instead, they rely heavily on the final, most risky step—offsets.

Yes, offsets can work—in very limited situations. They cannot replace the irreplaceable. And much of nature is irreplaceable.

Old-growth forests cannot be replaced. The same goes for tree hollows—these take hundreds of years to form, and artificial nesting boxes often don't work.

So, the move towards nature positive must not replace rigorous adherence to the mitigation hierarchy with more general environmental action which doesn't fully address damage.

Second, organizations must consider not just their direct impact on biodiversity, but the footprint of their whole operation and its resource use.

Achieving nature positive will mean tackling entire supply chains.

It's not easy to account for, reduce and compensate for your company or organization's unavoidable impacts on nature. But it can be done. It will require improvements in knowledge and traceability of supply chains, reducing consumption, and investing in nature restoration to make up for the leftover harms unable to be eliminated.

And third, organizations signing up to nature positive must contribute to active ecological restoration. That's on top of any compensation for their own direct and indirect impacts. The huge scale of historical damage to the environment means that even if organizations completely address all of their current and future biodiversity impacts, nature positive will still not be achieved.

Here, so-called voluntary biodiversity credits may play a useful role.

But wherever there are credits, there's risk. It's entirely possible companies could simply buy these credits without avoiding and minimizing biodiversity losses in the first place—the exact same problem plaguing carbon offsets.

Nature positive is welcome: Now let's see it in action

For decades, conservationists have tried to protect what's left of the natural world through lobbying for protected areas and better environmental laws. But nature's decline has only accelerated. Economic growth and profit have always taken precedence.

Moving to a truly nature positive world, one fit to provide future generations with all that we enjoy from nature, means a serious societal shift. For this reason, nature positive is welcome.

It's not enough to slow the decline—it's time to reverse it.

But we must not underestimate the task ahead.

Only if nature positive commitments are translated into action with rigor can they help reduce the damage we do, alongside spurring on ecological restoration and rewilding. But if nature positive is used as a tactic for positive publicity, it won't change a thing.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()