September 8, 2023 report

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Historically segregated parts of US cities found to have less bird data

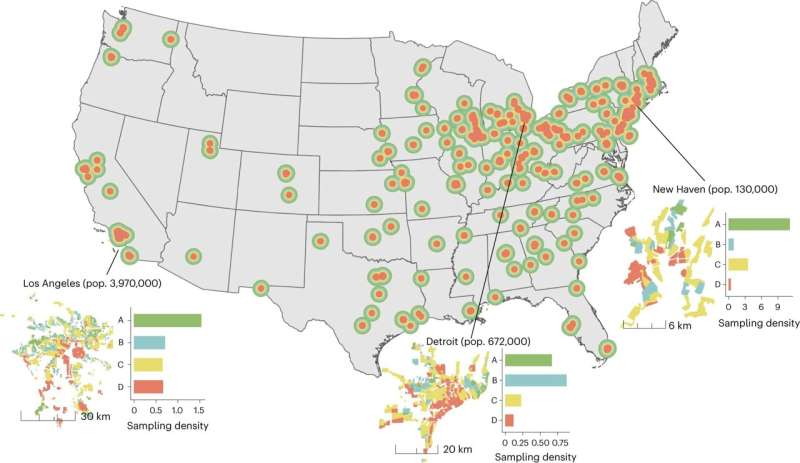

A trio of ecologists and environmental scientists from Yale University, the University of California, Berkeley and the USDA Forest Service, respectively, has found that parts of the United States that have been intentionally segregated over the past decades have less bird data available for study by ecologists.

In their paper published in the journal Nature Human Behavior, Diego Ellis-Soto, Melissa Chapman and Dexter Locke, describe how they analyzed bird sighting data in 9,000 neighborhoods across the U.S, and what they found by doing so.

Back in the 1930s, the U.S. government promoted a policy that has come to be known as "redlining," where parts of major cities were labeled as either red or green—green meant less investment risk. Such labels were based primarily on income levels and race.

Over time the policy led to the decline of red areas, leaving those people (primarily minorities) residing in such neighborhoods living in poverty. Redlining was eventually abolished but its impact remains. Many of the worst parts of cities in the U.S. today now exist in what were once redlined districts and remain mostly populated by minorities. In this new effort, the researchers have found that bird data collected by amateur birdwatchers in cities across the U.S. is far more sparse in formerly redlined districts.

As scientists around the world continue to grapple with the reality of global warming, many are attempting to understand what will happen to animals that do not have the luxury of living in air-conditioned environments. In this new effort, the researchers wondered what might happen to the birds that live across the United States.

To find out, they sought to learn more about their population numbers—data for which is typically available courtesy of amateur birdwatchers who report what they see in their local environment to ecology groups. But as they were analyzing their data they noticed some discrepancies—there was far less data available for historically segregated neighborhoods—going back decades.

In taking a closer look, the research team found that these areas with little bird data included the very same neighborhoods that had once been redlined. They have concluded that their study is one of the first to show how systemic racial segregation has resulted in playing a role in study of the ecological process in a given region—or in this case, an entire country.

More information: Diego Ellis-Soto et al, Historical redlining is associated with increasing geographical disparities in bird biodiversity sampling in the United States, Nature Human Behaviour (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-023-01688-5

Journal information: Nature Human Behaviour

© 2023 Science X Network