This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

preprint

trusted source

proofread

The case for a small universe

The universe is big, as Douglas Adams would say.

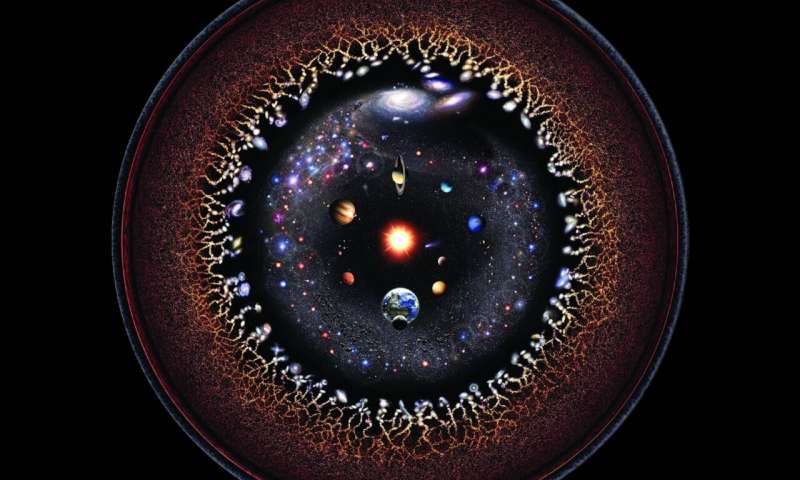

The most distant light we can see is the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which has taken more than 13 billion years to reach us. This marks the edge of the observable universe, and while you might think that means the universe is 26 billion light-years across, thanks to cosmic expansion it is now closer to 46 billion light-years across. By any measure, this is pretty darn big. But most cosmologists think the universe is much larger than our observable corner of it. That what we can see is a small part of an unimaginably vast, if not infinite creation. However, a new paper published on the arXiv preprint server argues that the observable universe is mostly all there is.

In other words, on a cosmic scale, the universe is quite small.

There are several reasons why cosmologists think the universe is large. One is the distribution of galaxy clusters. If the universe didn't extend beyond what we see, the most distant galaxies would feel a gravitational pull toward our region of the cosmos, but not away from us, leading to asymmetrical clustering. Since galaxies cluster at around the same scale throughout the visible universe. In other words, the observable universe is homogenous and isotropic.

A second point is that spacetime is flat. If spacetime weren't flat, our view of distant galaxies would be distorted, making them appear much larger or smaller than they actually are. Distant galaxies do appear slightly larger due to cosmic expansion, but not in a way that implies an overall curvature to spacetime. Based on the limits of our observations, the flatness of the cosmos implies it is at least 400 times larger than the observable universe.

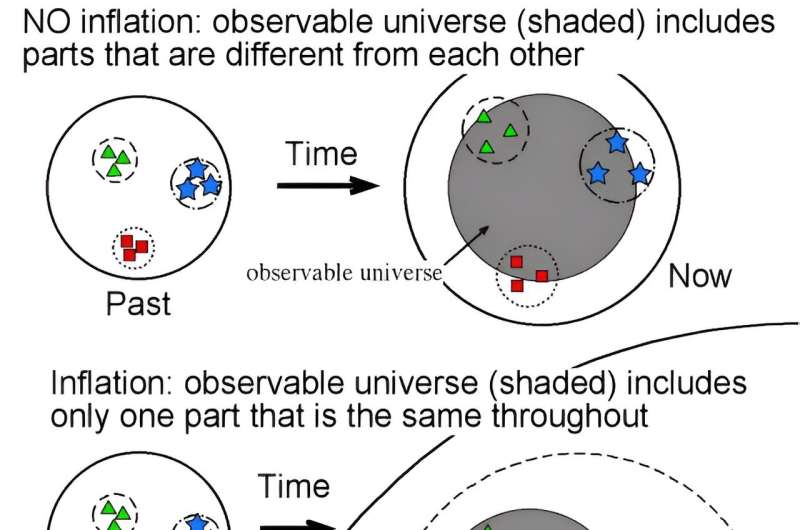

Then there is the fact that the cosmic microwave background is almost a perfect blackbody. There are small fluctuations in its temperature, but it is much more uniform than it should be. To account for this, astronomers have proposed a period of tremendous expansion just after the Big Bang, known as early cosmic inflation. We have not observed any direct evidence of it, but the model solves so many cosmological problems that it's widely accepted. If the model is accurate, then the universe is on the order of 1026 times larger than the observable universe.

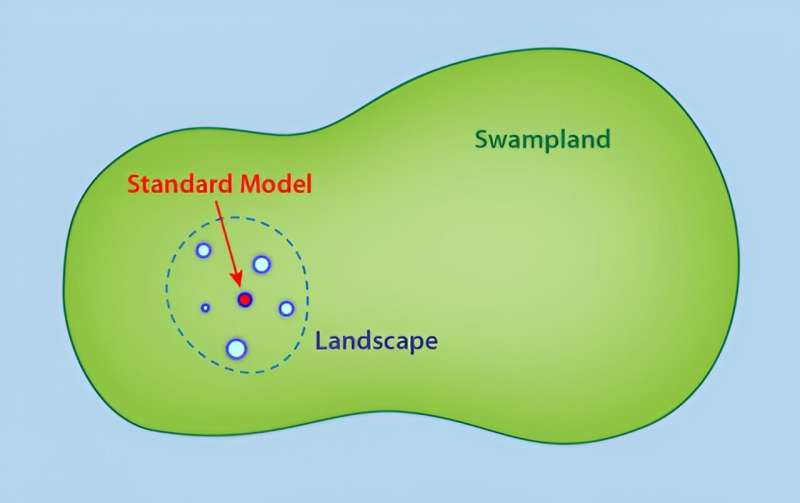

So given all of this theoretical and observational evidence, how could anyone argue that the universe is small? It has to do with string theory and the swamplands.

Although string theory is often presented as a physical theory, it's actually a collection of mathematical methods. It can be used in the development of complex physical models, but it can also just be mathematics for its own sake. One of the problems with connecting the mathematics of string theory to physical models is that the effects would only be seen in the most extreme situations, and we don't have enough observational data to rule out various models. However, some string theory models appear much more promising than others. For example, some models are compatible with quantum gravity, and others are not. So often theorists will define a "swampland" of theories that aren't promising.

When you separate the promising theoretical lands from the swamp, what you are left with are theories where early cosmic inflation isn't an option. Most of the inflationary string theory models are in the swampland. This leads one to ask whether you could construct a model cosmology that matches observation without early inflation. Which brings us to this new study.

One way to get around early cosmic inflation is to look at higher-dimensional structures. Classic general relativity relies upon four physical dimensions, three of space and one of time, or 3+1. Mathematically you could imagine a 3+2 universe or 4+1, where the global structure can be embedded into an effective 3+1 structure. This is a common approach in string theory since it isn't limited to the standard structure of general relativity.

The authors demonstrate that under just the right conditions, you could construct a higher-dimensional structure within string theory that matches observation and avoids the swampland. Based on their toy models, the universe may only be a hundred or a thousand times larger than the observed universe. Still big, but downright tiny when compared to the early inflation models.

All of this is pretty speculative, but in a way so is early cosmic inflation. If early cosmic inflation is true, we should be able to observe its effect through gravitational waves in the somewhat near future. If that fails, it might be worth looking more closely at string theory models that keep us out of the theoretical swamp.

More information: Jean-Luc Lehners et al, A small Universe, arXiv (2023). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2309.03272

Journal information: arXiv

Provided by Universe Today