This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

New bacteria discovery could lead to better treatments for people with cystic fibrosis

New research led by Queen's University Belfast has made a breakthrough in the field of microbiology, which could lead to the development of new treatments for people with compromised immune systems, such as those with cystic fibrosis.

To conduct their study the researchers looked at the bacterium Achromobacter, which can cause chronic lung infection and tissue damage in the airways.

The study reveals how this bacterium overcomes the body's immune defenses to multiply and continue to grow. The findings have been published in Cell Reports.

Professor Miguel A. Valvano, Chair in Microbiology and Infectious Diseases at the Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine (WWIEM) at Queen's University Belfast and lead researcher on the study, explains, "Achromobacter bacteria can cause chronic and potentially severe infections. However, until now, how this opportunistic bacterium interacts with the human immune system has been poorly understood.

"These bacteria resist the action of multiple antibiotics; therefore, infection by these microorganisms is very difficult to treat by conventional therapies, especially in people living with cystic fibrosis or other immunocompromising conditions, such as patients on chemotherapy."

The research was led by scientists from the Valvano Group in the WWIEM at Queen's. The research team includes Dr. Keren Turton, Hannah Parks and Paulina Zarodkiewicz, and was conducted in collaboration with Dr. Rebecca Coll and Dr. Rebecca Ingram, also in the WWIEM, and Professor Clare Bryant from the University of Cambridge.

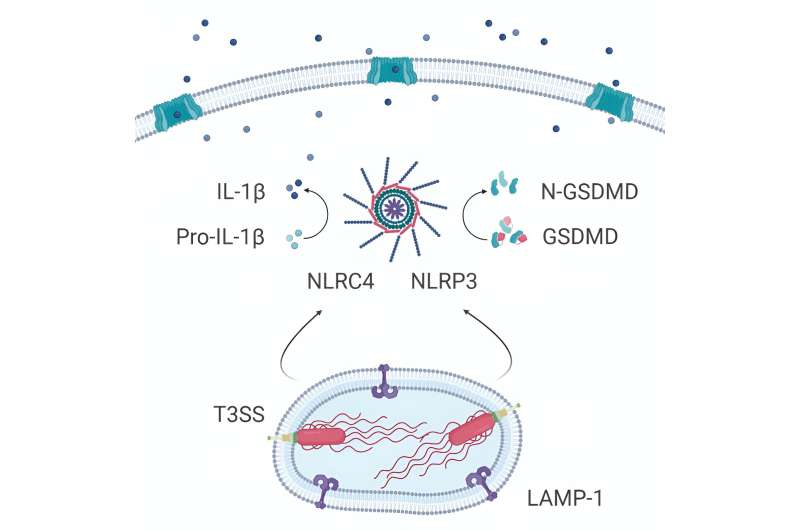

The team discovered that after being engulfed by the body's immune cells (macrophages), these bacteria can survive within cells using a specialized protein complex (called type III secretion system) to deploy molecules that induce the death of immune cells. Self-destruction of immune cells sounds an alarm that results in the recruitment of other immune cells to fight off invaders.

However, immune cells deficient in two of the inflammation sensors, called NLRC4 and NLRP3, do not die, suggesting that these two sensors are required for the recognition of the pathogen.

The researchers observed that Achromobacter infection leads to damage in lung structure and causes severe illness if the specialized secretory pathway is functional, but not if bacteria carry mutations in the secretion system.

This demonstrates that the macrophages' self-destruct alarm is triggered by the type III secretory system pathway but that this inflammatory response is insufficient for the immune system to defeat the bacteria.

The next stage of the research is to determine what other virulence proteins are in the Achromobacter armamentarium, helping it survive and invade other cell types in the body. The type III secretion system or other proteins could be useful for developing novel treatments.

More information: Keren Turton et al, The Achromobacter type 3 secretion system drives pyroptosis and immunopathology via independent activation of NLRC4 and NLRP3 inflammasomes, Cell Reports (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113012

Journal information: Cell Reports

Provided by Queen's University Belfast