This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Advanced imaging reveals the last bite of a 465-million-year-old trilobite

Paleontologists from the Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, and their colleagues describes a 465-million-year-old trilobite with preserved gut contents in a new study. The research was published in Nature.

This unique fossil, three-dimensionally preserved in a so-called Rokycany ball, was found more than a hundred years ago. But it has revealed its secrets only now, thanks to the cutting-edge imaging methods of synchrotron tomography. The research fills a fundamental gap in our understanding of trilobite ecology and their role in Paleozoic ecosystems.

The fossilized trilobite was discovered by a private collector, Karel Holub, already in 1908 and has since been housed in the museum of Rokycany (today the Museum of B. Horák, part of the Museum of West Bohemia in Pilsen). "I remember this specimen from my childhood," says the first author of the study, Petr Kraft from the Faculty of Science of the CU, "it was my grandfather's favorite fossil. That is why its photo once hung in the office of paleontology at the Rokycany museum, where he volunteered."

But it was not until the beginning of the 21st century that paleontologists realized that the bits of shells visible in the peeled-off median axis of the trilobite's trunk could represent preserved digestive tract contents. At that time, it was impossible to examine them without destroying the rare fossil.

A breakthrough came with the use of a powerful tool called synchrotron tomography, which enabled the scientists to non-destructively image all the shell fragments in the gut at high resolution. The Rokycany trilobite is among the first Czech fossils that were examined at the European Synchrotron (ESRF) in Grenoble, France.

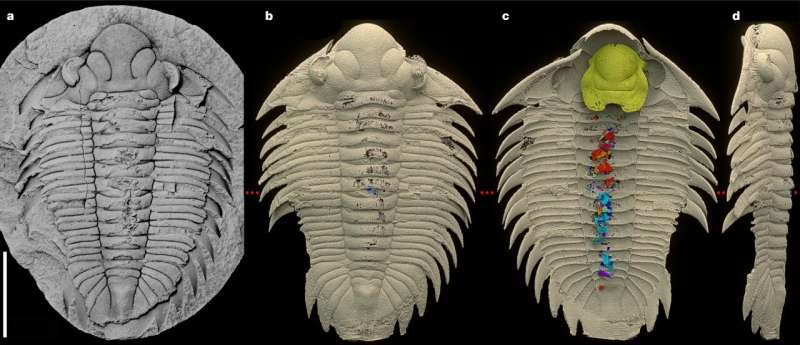

"Obtaining slice images, similar to what most people know from hospital CT scans, is only the first step. This is followed by manual segmentation of individual structures using a reconstruction software. The three-dimensional model of the fossil is then rendered in a virtual photo studio, which increases the image depth and results in an extremely informative figure," says Valéria Vaškaninová from the Faculty of Science of the CU, who first used this time-consuming but effective combination of imaging methods in a paper on the origin of vertebrate teeth published in 2020 in Science.

The digestive tract of the trilobite Bohemolichas incola was tightly packed with calcareous shells and their fragments that belonged to marine invertebrates such as ostracods, bivalves and echinoderms, some of them identifiable to the species level. The authors propose that the trilobite was an opportunistic scavenger, a light crusher and a chance feeder that ate dead or living animals, which either disintegrated easily or were small enough to be swallowed whole, without any attempt to reject the hard shells.

It is remarkable that even the thin-walled calcareous shells are not even partially dissolved throughout the digestive tract. This indicates that they were not exposed to an acidic environment. A near-neutral or slightly alkaline gut environment can also be observed in modern crustaceans and horseshoe crabs, suggesting that it might be an ancestral character of arthropods.

After death, this scavenger became scavenged. The researchers discovered numerous tracks of tiny scavengers that burrowed into the trilobite's carcass buried in a shallow depth in the muddy sea floor.

They apparently targeted soft tissue but avoided the gut, which is unusual. The scavengers may have sensed that the internal environment of the digestive tract was noxious and contained still-functioning digestive enzymes. But they were also unlucky as they were soon trapped by a solid "ball" rapidly forming around the dead trilobite, as evidenced by the absence of exit tracks.

More information: Petr Kraft et al., Uniquely preserved gut contents illuminate trilobite palaeophysiology, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06567-7. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06567-7

Provided by Charles University