HETDEX project on track to probe dark energy

Three years into its quest to reveal the nature of dark energy, the Hobby-Eberly Telescope Dark Energy Experiment (HETDEX) is on track to complete the largest map of the cosmos ever. The team will create a three-dimensional map of 2.5 million galaxies that will help astronomers understand how and why the expansion of the universe is speeding up over time.

"HETDEX represents the coming together of many astronomers and institutions to conduct the first major study of how dark energy changes over time," said Taft Armandroff, director of The University of Texas at Austin's McDonald Observatory.

The survey began in January 2017 on the 10-meter Hobby-Eberly Telescope (HET) at McDonald Observatory. Today, the survey is 38% complete. Data reduction and analysis are continuing.

"HETDEX has arrived," said astronomer Karl Gebhardt. "We're over a third of the way through our program now, and we have this fantastic data set that we're going to use to measure the dark energy evolution."

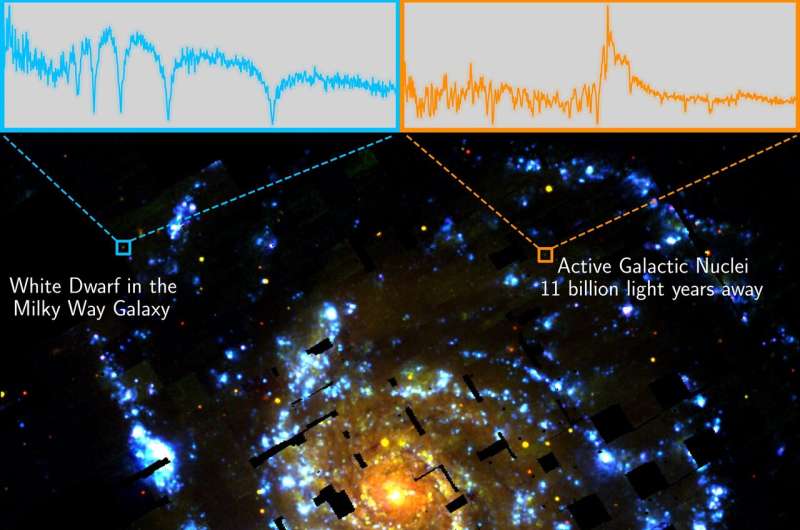

The survey works by aiming the telescope at two regions of the sky near the Big Dipper and Orion. For each pointing, the telescope records around 32,000 spectra, capturing the cosmic fingerprint of the light from every object within the telescope's field of view.

"It's actually a little mind-blowing, how much information is captured in this," said team member Gary Hill.

These spectra are recorded via 32,000 optical fibers that feed into more than 100 instruments working together as one. This assembly is called VIRUS, the Visible Integral-field Replicable Unit Spectrograph. It's a massive machine made up of dozens of copies of an instrument working together for efficiency. VIRUS was designed and built especially for HETDEX.

This makes VIRUS one of the most advanced astronomical instruments in the world. Building it "was quite a task to orchestrate," Hill said, noting that the project has taken a decade to reach fruition. "It's the largest on many measures," he said, noting that it has the most optical fibers, as well as having as much detector area as the largest astronomical cameras. It's also an extremely large instrument, taking up much of the room inside the telescope dome.

HETDEX is a blind survey, meaning that rather than pointing at specific targets, it records everything over a specific patch of sky. Then scientists go through the data to sift out objects they want to study.

Team member Phillip MacQueen has worked on the technical challenges of delivering VIRUS to the HETDEX specifications. He reminds us that map making in astronomy started with the first people who looked at the sky.

"VIRUS is an astronomical cartographer's delight," MacQueen said. "It does much more than map where objects are in two dimensions on the sky. HETDEX is using VIRUS to map where objects lie in a truly enormous volume of the universe, both within our galaxy and far beyond it."

To make the map needed for the dark energy project, they are combing through a billion spectra looking for examples of a specific type of galaxy. These galaxies range in distances from 10 billion to 11.7 billion light-years away, so they represent an epoch when the universe was only a few billion years old. Their spectra carry information about how fast the galaxies are moving away from us as a result of the expansion of the universe. That will allow astronomers to determine how the rate at which the universe expands has changed over the eons, which is key to determining the nature of dark energy.

The HETDEX team expects to complete their observations by December 2023. In total, the completed survey will include 1 billion spectra, "the largest ever spectral survey by far," Gebhardt said. These data are processed and stored at UT Austin's Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC), one of the top supercomputing centers in the world.

Erin Mentuch Cooper is the project's data manager. "We're very fortunate to have access" to TACC, she said, explaining that during the summer, a TACC supercomputer processed all of the HETDEX data now in hand in two weeks. It would have taken a single computer 10 years, she said.

Meanwhile, many astronomers are using the data already collected to attack a number of other astronomical mysteries. Several are on the verge of publishing their research.

Among them is UT professor Keith Hawkins. He has made use of the survey's spectra of about 100,000 stars in our own Milky Way galaxy. Though these stars were not the main quarry for HETDEX, they were captured by the blind survey. "As my grandfather used to say, "One man's trash is another man's treasure,'" he said.

Hawkins is using these spectra to study the stars' contents, sizes, temperatures and motions to trace how the different parts of our galaxy came together. His research paper on this work will be published soon. Other astronomers are preparing to publish research on white dwarfs and nearby galaxies for which they used HETDEX data.

Provided by University of Texas at Austin