Big-boned marsupial unearths evolution of wombat burrowing behavior

The discovery of a new species of ancient marsupial, named Mukupirna nambensis, is reported this week in Scientific Reports. The anatomical features of the specimen, which represents one of the oldest known Australian marsupials discovered so far, add to our understanding of the evolution of modern wombats and their characteristic burrowing behavior.

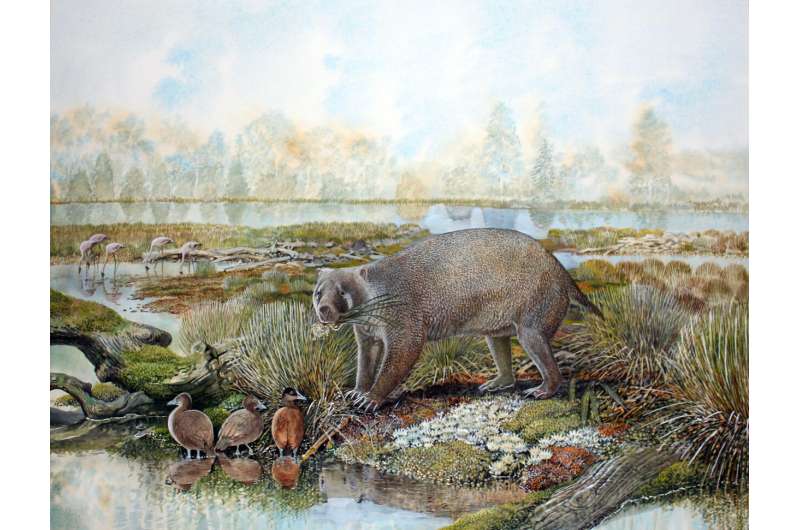

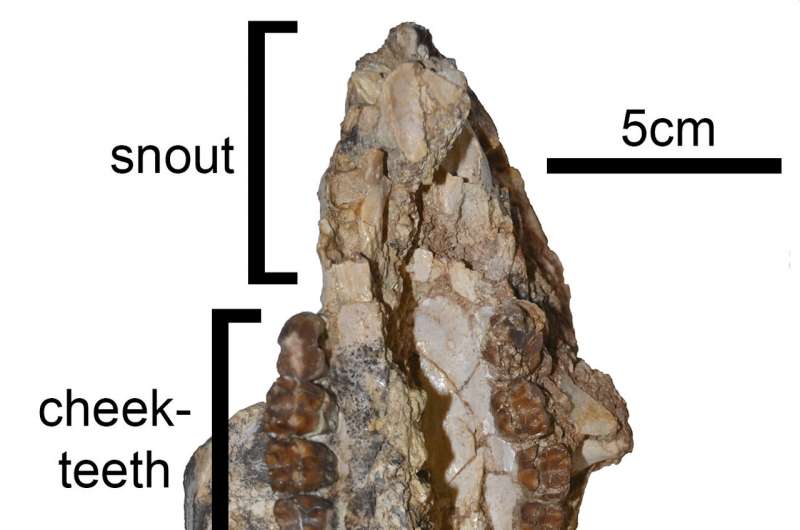

Robin Beck and colleagues describe the remains of a skull and partial skeleton from the Lake Eyre Basin of South Australia. The fossil dates back to the late Oligocene period ― approximately 25–26 million years ago ― and belongs to a new species of Vombatiformes, once one of the most diverse evolutionary groups of marsupial, of which only three species of wombat and the koala are alive today. The authors name the species Mukupirna nambensis from the words muku ("bones") and pirna ("big") of the Dieri and Malyangapa languages spoken in the surrounding areas of Lake Eyre and Lake Frome. The creature's body mass is estimated to have been between 143–171kg, roughly five times larger than living wombat species.

A number of anatomical features identified in the skeleton are indicative of digging behavior, such as adaptations to the forearms commonly seen in burrowing animals. Yet, evidence from previous fossils dated to a later time, suggest Mukupirna was less well-adapted to burrowing than its later relatives. Given this and its size, Mukupirna may not have been capable of the true burrowing behavior seen in modern wombats, but may have used scratch-digging to access food items below the surface, such as roots and tubers. Another adaptation characteristic of living wombat species ― specialized molars capable of continuous growth ― were also absent, suggesting anatomical adaptations of the skeleton for digging pre-date dental changes in wombat evolution.

More information: A new family of diprotodontian marsupials from the latest Oligocene of Australia and the evolution of wombats, koalas, and their relatives (Vombatiformes), Scientific Reports (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-66425-8 , www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-66425-8

Journal information: Scientific Reports

Provided by Nature Publishing Group