January 24, 2020 feature

Adding memory to pressure-sensitive phosphors

Mechanoluminescence (ML) is a type of luminescence induced by any mechanical action on a solid, leading to a range of applications in materials research, photonics and optics. For instance, the mechanical action can release energy previously stored in the crystal lattice of phosphor via trapped charge carriers. However, the method has limits when recording ML emissions during a pressure-induced event. In a new study, Robin R. Petit and a research team at the LumiLab, Department of Solid State Sciences at the Ghent University—Belgium devised a new technique to add a memory function to pressure-sensitive phosphors. Using the method, the scientists obtained an optical readout of the location and intensity of a pressure event three days (72 hours) after the event.

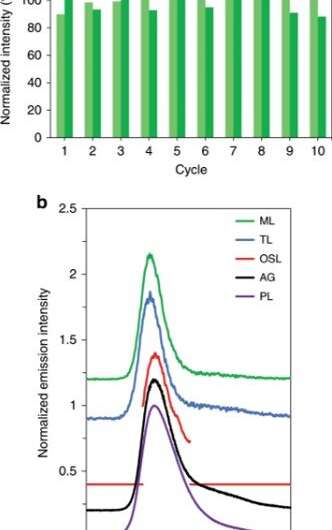

The team noted the outcome using Europium-doped barium silicon oxynitride (BaSiO2N2:Eu2+) phosphor, which contained a broad trap depth distribution or depth of defect distribution—essential for the unique memory function. The excited electrons of phosphor filled the 'traps' (or defects) in the crystal lattice, which could be emptied by applying weight to emit light. The research team merged optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), thermoluminescence (TL) and ML measurements to carefully analyze the influence of light, heat and pressure on trap depth distribution. Based on the memory effect, the materials remembered the location at which pressure had occurred, helping researchers to develop new pressure sensing applications and study charge carrier transitions within energy storage phosphors. The work is now published on Light: Science & Applications.

When specific materials are subjected to mechanical action, light emission can be observed as mechanoluminescence (ML). The process can be induced through different types of mechanical stress including friction, fracture, bending, impact of a weight and even ultrasound, crystallization and wind. The phenomenon can be used to identify stress distribution, microcrack propagation and structural damages in solids, while allowing a variety of applications in displays, to visualize ultrasound and even map personalized handwriting. However, the technique is limited by the range of emission colors, restriction of real-time measurements and restricted signal visibility.

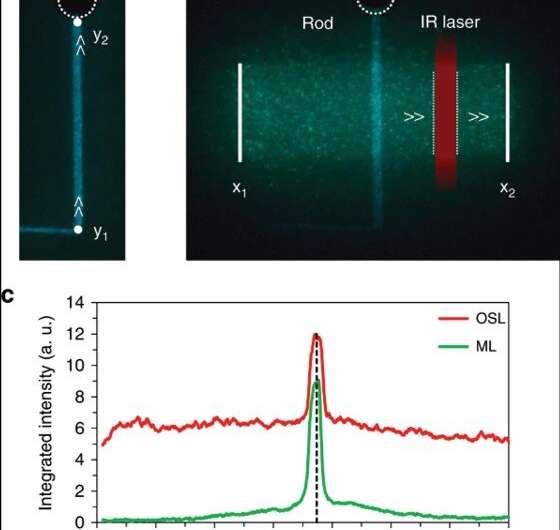

Using Eu2+ doped BaSiO2N2 phosphor as an example, the scientists first excited the phosphor with ultraviolet (UV) or blue light to bring it into an excited state. When the ion transited back to the ground state, they observed a blue-green emission of color. Researchers had previously shown that thermally assisted detrapping (electron removal from a trap) allowed 'glow-in-the-dark' phosphors for safety signage or bioimaging functions. Applying pressure in the setup similarly induced detrapping for thermal- and pressure-induced detrapping to become competing processes. The scientists avoided the presence of background emission or afterglow in the setup to increase visibility of the signal. In this work, Petit et al. introduced the pressure memory (P-MEM) property, which allowed phosphor particles that were subjected to pressure to remember the process under infrared radiation (IR) more than 72 hours after pressure application.

The team investigated the underlying working principles of the P-MEM (pressure-memory) property using a relatively large range of trap depths within the phosphor where different traps responded differently to specific stimuli (pressure, heat, light). When they mechanically induced detrapping some of the charge carriers recombined to yield immediate light emission while others were redistributed across relatively shallow traps or almost permanently stored in deep traps. To release the charges in deep traps they used IR radiation. The work opens new avenues for pressure sensing and facilitates the study of energy storage phosphors by probing subtle interactions between thermal, mechanical and optical detrapping.

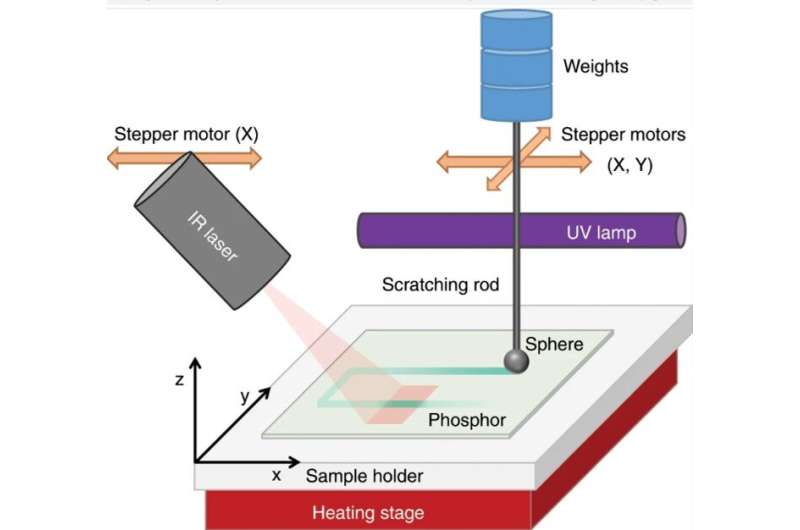

To test reproducibility of the ML tests, the scientists first performed mechanical stimulation by non-destructively dragging a spherical-shaped rod across the surface of the phosphor. They guaranteed reproducibility of the measurements by recovering the initial ML intensity after each UV excitation step. The capacity of active storage traps remained unaltered due to mechanical stimulation, while the dragging process remained non-destructive. To achieve the P-MEM property, the team combined mechanical and optical stimulations in the lab, they used pressure to move the electrons and used optical means to read-out the results.

First, they exposed the crystal to UV light followed by ML stimulation by dragging a rod back and forth several times, then irradiated the sample using the IR laser. During IR stimulation, the emission spectrum originated from the Eu2+ luminescent center in BaSiO2N2. The team investigated the relationship between the luminescence intensity and magnitude of the load in the experiment; which increased linearly with the applied load. Applying higher loads for mechanical stimulation emptied more traps in the crystal to release more charge carriers. Some of the released electrons recombined immediately with ionized europium ions to yield the common ML signal.

After extensively testing the setup, Petit et al. observed the origin of P-MEM using thermoluminescence (TL) to reveal the occupation of traps in phosphors. For this, they divided the TL-glow curves in to three regions containing a shallow (25 degrees C to 45 degrees C), intermediate (45 degrees C to 80 degrees C) and deep trap region (>80 degrees ). The results implied that the P-MEM property was based on a reshuffling event to release charge carriers that occupied deep trap levels.

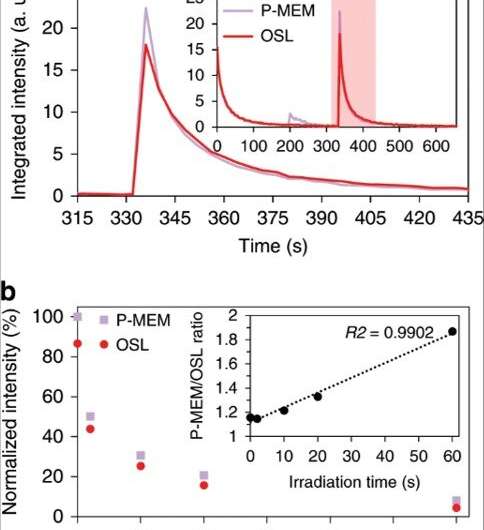

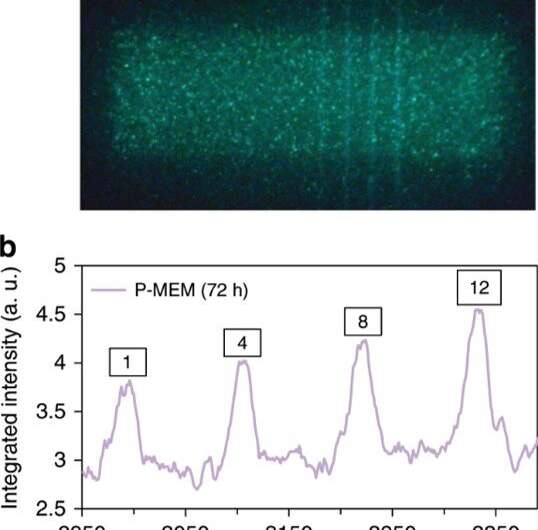

It was equally important for the research team to visualize the P-MEM signal as a function of time. They achieved this by performing a dedicated experiment to test the influence of IR irradiation and observed two effects relative to (1) emptying of deep trap levels, followed by the (2) subsequent decay originating from the gradual depletion of shallow and intermediate trap levels. Due to the stability of deep traps, after optimizing the setup, the team observed the P-MEM signal with sufficient intensity—three days after the application of pressure and IR-irradiation assisted readout.

In this way, Robin R. Petit and colleagues detailed a specific interaction between mechanical and optical detrapping in BaSiO2N2:Eu2+, which led to the unique P-MEM property observed in the study. They recovered a pressure-induced ML signal after IR irradiation of the phosphor, based on the detailed interactions. When they conducted optical detrapping with IR irradiation, the deeper traps emptied rapidly to create an increased signal strength at places where pressure had previously occurred, even 72 hours between the pressure stimuli and IR readout. The deep traps played a significant role in obtaining the P-MEM phenomenon and can be extended to even longer hours.

The work opens a new path for information storage and retrieval, while mechanical stimulation provides a unique way to write information. The described P-MEM has great potential within structural health monitoring applications and in biomedicine. The comprehensive results indicate that much remains to be understood on the inner workings of luminescent phenomena relative to detrapping and retrapping routes, warranting further in-depth research.

More information: Robin R. Petit et al. Adding memory to pressure-sensitive phosphors, Light: Science & Applications (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41377-019-0235-x

Thomas Maldiney et al. The in vivo activation of persistent nanophosphors for optical imaging of vascularization, tumours and grafted cells, Nature Materials (2014). DOI: 10.1038/nmat3908

Chao-Nan Xu et al. Direct view of stress distribution in solid by mechanoluminescence, Applied Physics Letters (2002). DOI: 10.1063/1.123865

Journal information: Nature Materials , Light: Science & Applications , Applied Physics Letters

© 2020 Science X Network