French scientists claim to have created metallic hydrogen

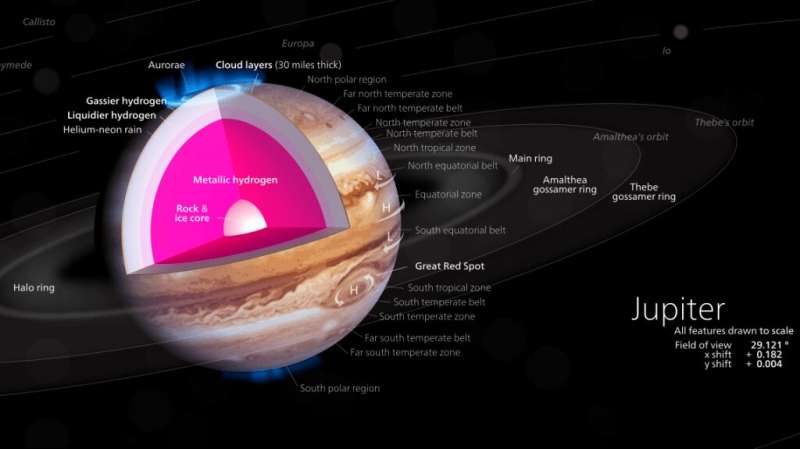

Scientists have long speculated that at the heart of a gas giant, the laws of material physics exhibit remarkable characteristics. In these kinds of extreme pressure environments, hydrogen gas is compressed to the point that it actually becomes a metal. For years, scientists have been looking for a way to create metallic hydrogen synthetically because of the endless applications it would offer.

At present, the only known way to do this is to compress hydrogen atoms using a diamond anvil until they change their state. And after decades of attempts (and 80 years since it was first theorized), a team of French scientists may finally have created metallic hydrogen in a laboratory setting. While there is plenty of skepticism, there are many in scientific community who believe this latest claim could be true.

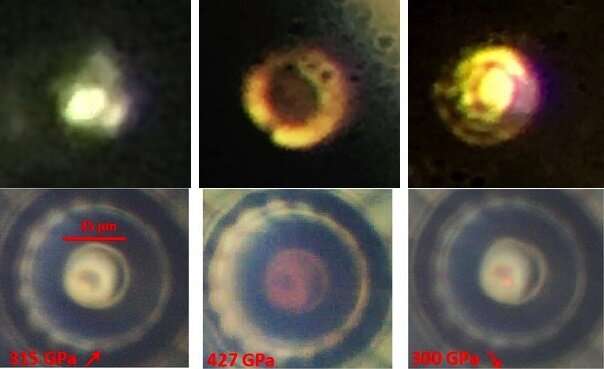

The study describing their experiment, titled "Observation of a first order phase transition to metal hydrogen near425 GPa," recently appeared on the arXiv preprint server. The team consisted of Paul Dumas, Paul Loubeyre, and Florent Occelli, three researchers from the Division of Military applications (DAM) at the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission and the Synchrotron SOLEIL research facility.

As they indicate in their study, it is indisputable that "metal hydrogen should exist," thanks to the rules of quantum confinement. Specifically, they indicate that if the electrons of any material are restricted enough in their motion, what is known as the "band gap closure" will eventually take place. In short, any insulator material (like oxygen) should become a conductive metal if it is pressurized enough.

They also explain how two advances made their experiment possible. The first has to do with the diamond anvil setup they used, which had toroidal (donut-shaped) diamond tips instead of flat tips. This allowed the team to push past the previous pressure limit established by other diamond anvils (400 GPa) and get as high as 600 Gpa.

The second innovation involved a new type of infrared spectrometer the research team designed themselves at the Synchrotron SOLEIL facility, which allowed them to measure the sample. Once their hydrogen sample had reached pressures of 425 GPa and temperatures of 80 K (-193 °C; -316 °F), they reported that it began absorbing all the infrared radiation, thereby indicating that they had "closed the band gap."

These results have attracted their fair share of criticism and skepticism, largely because previous claims of metallic hydrogen synthesis were either proven to be false or inconclusive. In addition, this latest study has yet to be peer reviewed, and the experiment validated by other physicists.

However, the French team and their experimental results have some powerful allies. One person is Maddury Somayazulu, an associate research professor at the Argonne National Laboratory who was not involved in this study. As he said in an interview with Gizmodo, "I think this is really a Nobel prize-worthy discovery. It always was, but this probably represents one of the cleanest and most comprehensive pieces of work on pure hydrogen."

Somayazulu also expressed that he knows the study's lead author Paul Dumas "very well," and that Dumas is an "incredibly careful and systematic scientist." Another physicist who spoke positively of this latest experiment is Alexander Goncharov, a staff scientist from the Carnegie Institute for Science's Geophysical Laboratory.

In 2017, he expressed doubt when a research team from Harvard University's Lyman Laboratory of Physics claimed to have created metallic hydrogen using a similar process. But as Goncharov told Gizmodo of this latest experiment, "I think that the paper contains some good evidence about the band gap closure in hydrogen. Some of the interpretation is incorrect and some data could be better, but I generally trust that this is valid."

As a synthetic material, metallic hydrogen would also have endless applications. First off, it is believed to have superconducting properties at room temperature, and is meta-stable (meaning that it will retain its solidity once it returns to normal pressure). These properties would make it incredibly useful in electronics.

It would also be a boon for scientists engaged in high-energy research and physics, like that currently being conducted at CERN. On top of all that, it would allow astrophysicists, for the first time ever, to study what conditions are like in the interior of giant planets without actually having to dispatch probes to explore them.

In this respect, metallic hydrogen is a lot like cold fusion. Given the immense payoffs, anyone who claims to have achieved it is naturally going to face some tough questions. All we can do is hope that the latest experiments were successful, and either celebrate or wait for the next attempt.

More information: Paul Loubeyre, et al. Observation of a first order phase transition to metal hydrogen near 425 GPa. arXiv:1906.05634v1 [cond-mat.mtrl-sci]: Preprint PDF: arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1906/1906.05634.pdf

Source Universe Today