Water vapor annealing technique on diamond surfaces for next-generation power devices

Diamonds are often displayed in exquisite jewelry. But this solid form of carbon is also renowned for its outstanding physical and electronic properties. In Japan, a collaboration between researchers at Kanazawa University's Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology and AIST in Tsukuba, led by Ryo Yoshida, has used water vapor annealing to form hydroxyl-terminated diamond surfaces that are atomically flat.

Diamond has many characteristics that make it attractive for application in electronic devices. However, diamond contains defects that are observable at the atomic level that create unique surface properties influencing how it can be applied in such devices.

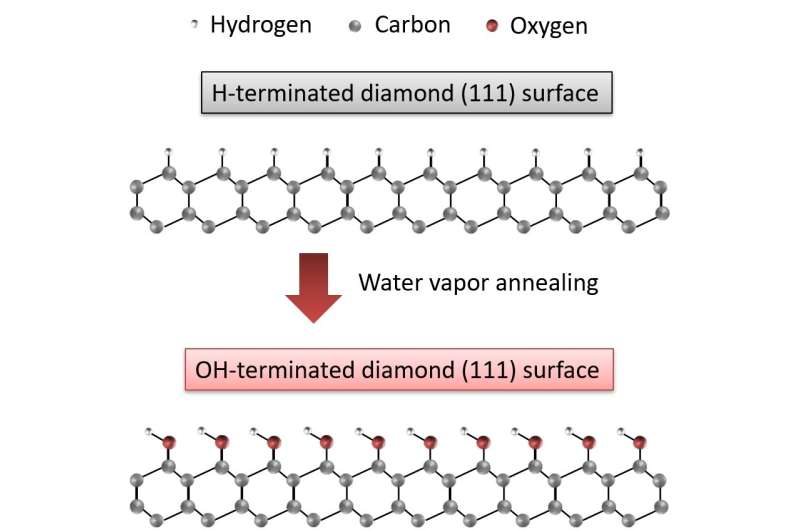

Surface termination using oxygen or hydrogen stabilizes the diamond structure. Hydrogen-terminated (H-terminated) diamond surfaces contain two-dimensional hole gas layers (2DHG) that allow high-temperature and high-voltage operation. Oxygen-terminated diamond surfaces are formed by surface oxidation of H-terminated surfaces, which removes carbon-hydrogen (C-H) bonds and 2DHG, "but this roughens the diamond surface and leads to the degradation of performance of devices," says Norio Tokuda from Kanazawa University.

To overcome this, the researchers applied the water vapor annealing. They began with (1 1 1)-oriented high-pressure, high-temperature synthetic single-crystalline diamond Ib and IIa substrates. Homoepitaxial diamond films were grown on the Ib substrates via microwave plasma chemical vapor deposition (MPCVD). To obtain atomically flat H-terminated surfaces, the diamond samples were exposed to H-plasma in the MPCVD chamber. To form hydroxyl-terminated surfaces, the H-terminated diamond samples were subjected to water vapor annealing. The annealing treatment occurred under an atmosphere of nitrogen bubbled through ultrapure water in a quartz tube in an electric furnace.

The results indicated that C-H bonds remained on the diamond surface during water vapor annealing below 400°C; therefore, 2DHG was detected. "However, water vapor annealing above 500°C removed C-H bonds from the diamond surface," explains Yoshida, "indicating the disappearance of the 2DHG."

Thus, the results indicate that water vapor annealing can remove 2DHG while maintaining the surface morphology of (1 1 1)-oriented diamond surfaces. "Compared with conventional techniques to remove 2DHG, such as wet chemical oxidation," says Tokuda, "water vapor annealing offers the advantage of maintaining an atomically flat surface."

More information: Ryo Yoshida et al, Formation of atomically flat hydroxyl-terminated diamond (1 1 1) surfaces via water vapor annealing, Applied Surface Science (2018). DOI: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.07.094

Provided by Kanazawa University