Cas3: a biological fishing rod and a shredder rolled into one

CRISPR-Cas9 has made gene editing a lot easier, and will eventually contribute to elimination of hereditary diseases from our DNA. But despite the fact that researchers use CRISPR-Cas9 and similar bacterial immune systems as molecular tools, they still don't know how they work. For instance, an unanswered question about Cas3 is how it cuts DNA. Does it pull a DNA strand toward itself, or does it grab onto a strand and walk over it while cutting? Researchers at Delft University of Technology have now found the answer: Cas3 pulls DNA in like a fisherman reeling in his line.

It is not widely known that there are many more CRISPR systems than the one that uses the Cas9 protein. Each has slightly different properties. Instead of making a straight cut in the DNA, for instance, some proteins make an angular incision so that the material that researchers want to paste into the genome fits like a piece of a puzzle. This increases the chance that the DNA will be successfully rewritten.

The various CRISPR-Cas systems can be compared to tools. One job will require a screwdriver, while another requires a hammer. The good news is that the toolbox is rapidly expanding—researchers are still finding new CRISPR systems in nature. It is hoped that these new discoveries will eventually ensure that scientists can adapt the DNA in all possible cells.

This specific research project revolved around a standard system: the so-called Cascade complex, a lump of proteins that floats in the cytoplasm of E. coli and detects the DNA of viruses that try to infect the bacterium. When the Cascade complex encounters viral DNA, it clings to it and sends out a signal to the Cas3 protein. The Cascade complex then folds open, allowing Cas3 latch onto the lump.

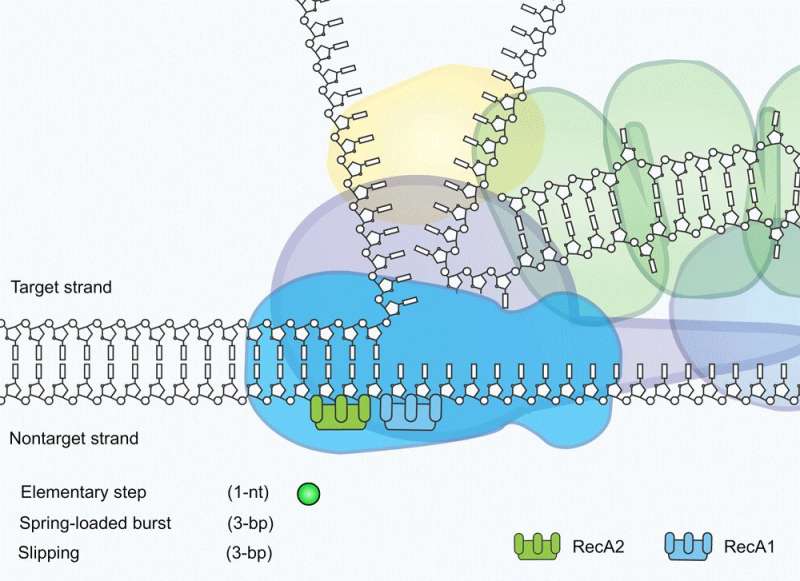

After that, the Cas3 protein starts degrading the viral DNA. First, the so-called helicase domain of Cas3 separates the double-stranded DNA like a zipper. The single-stranded DNA is then inserted into the nuclease domain of the Cas3 protein. Inside this protein, the invading DNA is then cut into small fragments. Cas3 can be compared to a "biological paper shredder," says research leader Luuk Loeff.

The most important question in this study was how exactly the Cas3 protein works. There were two theories. The most popular hypothesis was that the protein would disconnect from the Cascade complex after being presented with a strand of DNA. Then, according to this theory, the protein would walking along the DNA, cutting through it every so many steps. Another theory was that Cas3 stays with the Cascade complex the entire time, pulling in the DNA like a fisherman reeling in his line.

In their research, Loeff and colleagues used so-called single-molecule techniques, experiments that make it possible to look at the properties of individual molecules. They made DNA molecules fluorescent and observed how those fluorescence signals were transferred between the molecules. "Fluorescent molecules can be used as a sort of ruler at the nanoscale," Loeff explains. "They allow us to measure distances between one and ten nanometers, which is how large proteins such as Cas3 are."

The measurements carried out by the Delft researchers indicate that Cas3 stays where it is and pulls in the DNA in small steps—a so-called reeling mechanism. It struck the researchers that Cas3 turned out to be quite inefficient in doing so. While the protein reels in viral DNA, it also often lets go so that the DNA strand slips back a bit. Sometimes, the protein even lets a DNA strand slip away completely.

Loeff was initially surprised by the inefficiency of Cas3. But there is a logical explanation. "A bacterial cell contains a lot of its own DNA, including single-stranded DNA, and as a bacterium, you don't want Cas3 to accidentally destroy that material," he explains. "By letting the DNA slip repeatedly and then pulling it in again, the cell ensures that Cas3 only breaks down viral DNA in a controlled way so that the cell does not kill itself unexpectedly. It is a safeguard developed by evolution."

The findings could enable researchers to better control these biological mechanisms in the future, thus developing even more efficient and safe methods of gene editing.

More information: "Repetitive DNA reeling by the Cascade-Cas3 complex in nucleotide unwinding steps", Luuk Loeff, Stan J. J. Brouns, Chirlmin Joo, Molecular Cell

Journal information: Molecular Cell

Provided by Delft University of Technology