Astrophysicists release IllustrisTNG, the most advanced universe model of its kind

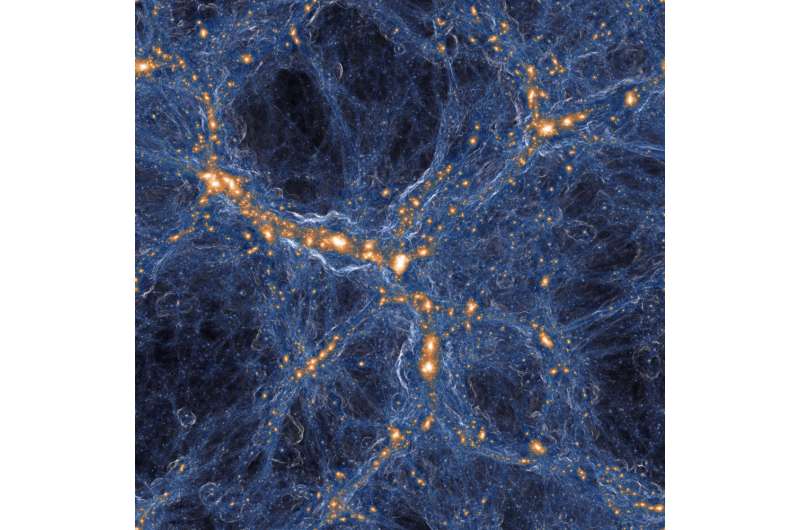

Novel computational methods have helped create the most information-packed universe-scale simulation ever produced. The new tool provides fresh insights into how black holes influence the distribution of dark matter, how heavy elements are produced and distributed throughout the cosmos, and where magnetic fields originate.

Led by principal investigator Volker Springel at the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies, astrophysicists from the Max Planck Institutes for Astronomy (MPIA, Heidelberg) and Astrophysics (MPA, Garching), Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and the Flatiron Institute's Center for Computational Astrophysics (CCA) developed and programmed the new universe simulation model, dubbed Illustris: The Next Generation, or IllustrisTNG.

The model is the most advanced universe simulation of its kind, says Shy Genel, an associate research scientist at CCA who helped develop and hone IllustrisTNG. The simulation's detail and scale enable Genel to study how galaxies form, evolve and grow in tandem with their star-formation activity. "When we observe galaxies using a telescope, we can only measure certain quantities," he says. "With the simulation, we can track all the properties for all these galaxies. And not just how the galaxy looks now, but its entire formation history." Mapping out the ways galaxies evolve in the simulation offers a glimpse of what our own Milky Way galaxy might have been like when the Earth formed and how our galaxy could change in the future, he says.

Mark Vogelsberger, an assistant professor of physics at MIT and the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, has been working to develop, test and analyze the new IllustrisTNG simulations. Along with postdoctoral researchers Federico Marinacci and Paul Torrey, Vogelsberger has been using IllustrisTNG to study the observable signatures from large-scale magnetic fields that pervade the universe.

"The high resolution of IllustrisTNG combined with its sophisticated galaxy formation model allowed us to explore these questions of magnetic fields in more detail than with any previous cosmological simulations," says Vogelsberger, one of the authors of the three papers published today in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Modeling a (more) realistic universe

IllustrisTNG is a successor model to the original Illustris simulation developed by the same research team, but it has been updated to include some of the physical processes that play crucial roles in the formation and evolution of galaxies.

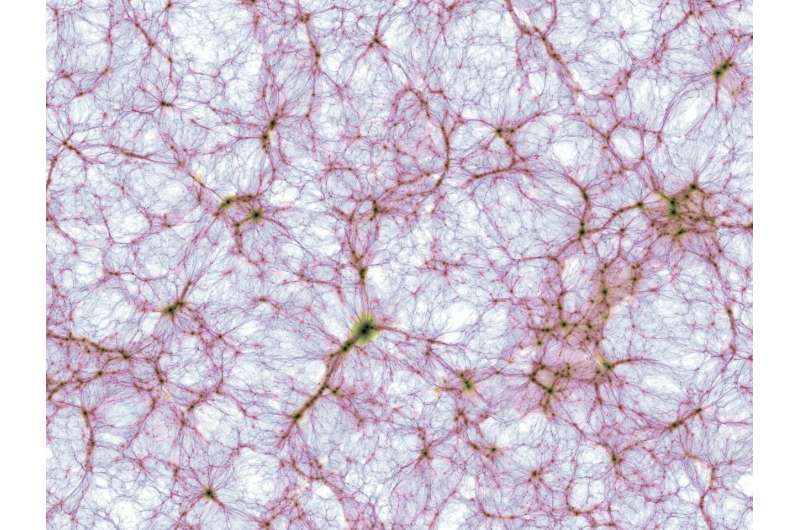

Like Illustris, the project models a cube-shaped universe smaller than our own. This time, the project followed the formation of millions of galaxies in a representative region of a universe with nearly 1 billion light-years per side (up from 350 million light-years per side just four years ago). lllustrisTNG is the largest hydrodynamic simulation project to date for the emergence of cosmic structures, says Springel, also of MPA and Heidelberg University.

The cosmic web of gas and dark matter predicted by IllustrisTNG produces galaxies quite similar to real galaxies in shape and size. For the first time, hydrodynamic simulations could directly compute the detailed clustering pattern of galaxies in space. In comparison with observational data - such as the data provided by the powerful Sloan Digital Sky Survey - the simulations from IllustrisTNG demonstrate a high degree of realism, says Springel.

In addition, the simulations predict how the cosmic web changes over time, especially in relation to the dark matter that underlies the cosmos. "It is particularly fascinating that we can accurately predict the influence of supermassive black holes on the distribution of matter out to large scales," says Springel. "This is crucial for reliably interpreting forthcoming cosmological measurements."

Astrophysics via code and supercomputers

For the project, the researchers developed a particularly powerful version of their highly parallel moving-mesh code AREPO and used it on the Hazel Hen machine, Germany's fastest mainframe computer, at the High Performance Computing Center Stuttgart. To compute one of the two main simulation runs, the team employed more than 24,000 processors over the course of more than two months. "The new simulations produced more than 500 terabytes of simulation data," says Springel. "Analyzing this huge mountain of data will keep us busy for years to come, and it promises many exciting new insights into different astrophysical processes."

Supermassive black holes squelch star formation

In another study, Dylan Nelson, a researcher at MPA, was able to demonstrate the impact of black holes on galaxies. Star-forming galaxies shine brightly in the blue light of their young stars until a sudden evolutionary shift halts the star formation, so that the galaxy becomes dominated by old, red stars and joins a graveyard full of old and dead galaxies.

"The only physical entity capable of extinguishing the star formation in our large elliptical galaxies are the supermassive black holes at their centers," explains Nelson. "The ultrafast outflows of these gravity traps reach velocities up to 10 percent of the speed of light and affect giant stellar systems that are billions of times larger than the comparably small black hole itself."

New findings for galaxy structure

IllustrisTNG also improves our understanding of the hierarchical structure of galaxy formation. Theorists argue that small galaxies should form first and then merge into ever-larger objects, driven by the relentless pull of gravity. The numerous galaxy collisions literally tear some galaxies apart and scatter their stars into wide orbits around the newly created large galaxies, which should give the galaxies a faint background glow of stellar light. These predicted pale stellar halos are very difficult to observe due to their low surface brightness, but IllustrisTNG was able to simulate exactly what astronomers should be looking for.

"Our predictions can now be systematically checked by observers," says Annalisa Pillepich, a researcher at MPIA, who led a further IllustrisTNG study. "This yields a critical test for the theoretical model of hierarchical galaxy formation."

More information: Volker Springel et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: matter and galaxy clustering, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2017). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stx3304

Dylan Nelson et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: the galaxy colour bimodality, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2017). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stx3040

Annalisa Pillepich et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: the stellar mass content of groups and clusters of galaxies, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2017). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stx3112

The AREPO simulation code www.h-its.org/tap-software-de/arepo-code/

Journal information: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Provided by Simons Foundation