Georgia official discounts threat of exposed voter records

After a researcher notified officials of a major security lapse at the center managing Georgia's election technology, leading computer scientists urged the state's top elections official to order a thorough outside probe to determine if its voting systems had been compromised.

There's no indication that happened.

At the same time, Secretary of State Brian Kemp contested a lawsuit demanding the state abandon its antiquated touchscreen voting machines , which are highly susceptible to being rigged by hackers in all-but-undetectable ways, and whose votes couldn't be reliably recounted.

And when voting-transparency activists sought a top-to-bottom review of state voting systems, Kemp's top lawyer told them it would cost $10,000 and take six months—extending well past a closely watched congressional runoff vote on June 20.

NEW FOCUS ON VOTING SECURITY

A state judge threw out that suit last Friday, but the issue gained new urgency this week when the researcher who originally detected the security lapse decided to go public. A misconfigured server, Logan Lamb discovered last August, had left Georgia's 6.7 million voter records and other sensitive files exposed to hackers.

And it may have been left unfixed for seven months.

The vulnerability might have allowed attackers to plant malware and possibly rig votes or wreak chaos with voter rolls by deleting or altering records—a major concern amid heightened sensitivity to state-sponsored Russian election hacking.

Kemp declined to speak to The Associated Press. Last week, though, he celebrated the lawsuit's dismissal, a rebuff to the "Ivy League professors"—many, in actuality, eminent computer scientists—who advised the plaintiffs and saying the judge determined "what we already know: Our voting machines in Georgia are safe and accurate."

Voting technology experts say the state can't know that for sure.

Voting machines like Georgia's, which neither use paper ballots nor keep hardcopy proof of voter intent, are inherently vulnerable to tampering, researchers say. University of South Carolina's Duncan Buell, one of the lawsuit advisors, compared the risk to driving in a heavy rain at 100 miles an hour.

The extent to which the state has examined its systems is unclear. During the lawsuit, Kemp ignored a request from the plaintiffs' advisors for a full forensic examination by the Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (CERT), said activist Marilyn Marks.

Last year, Kemp refused DHS offers to help secure his state elections systems—then complained that it was probing them anyway.

FEARS OF RUSSIAN HACKING

The security failure's extent was first reported Wednesday by Politico Magazine . Lamb, a 29-year-old Atlanta-based researcher, told the AP that the publication last week of a classified National Security Agency report ended his reluctance to go public. It describing a sophisticated scheme, allegedly by Russian military intelligence, to infiltrate local U.S. elections systems using phishing emails.

The NSA report offered the most detailed account yet of an attempt by foreign agents to probe the rickety and poorly funded U.S. elections system. DHS had previously reported attempts last year to gain unauthorized access to voter registration databases in 20 states—one of which, in Illinois, succeeded, though the state said no harm resulted.

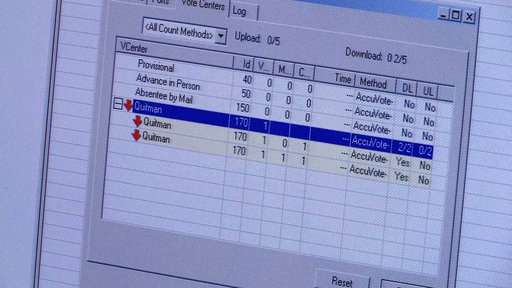

Lamb discovered the security hole as he did a search of the website of the Center for Election Systems at Kennesaw State, which manages voting statewide. There, he found a directory open to the internet that contained not just the state voter database, but PDF files with instructions and passwords used by poll workers to sign into a central server used on Election Day. Lamb said he downloaded 15 gigabytes of data, which he later destroyed.

The directory of files "was already indexed by Google," Lamb said in an interview—meaning that anyone could have found it with the right search.

"I don't know if the vote could have been rigged, but compromising that server would have served as a great pivot point and malware could have been planted easily," he added.

WHO KNEW WHAT WHEN

Lamb said he notified the center's director, Merle King, who assured him the hole would be patched and who asked to keep his discovery to himself.

But the center never notified the secretary of state's office of that discovery, said state election spokeswoman Candice Broce. The election center referred all questions to Kennesaw State, which declined comment.

Lamb said he decided at the time not to disclose the problem—mostly because he "didn't want to needlessly escalate things" prior to the Nov. 8 general election. He said King had also told him that "messing with elections means the people downtown crush you."

King did not respond to phone messages and emails seeking comment.

In March, a security colleague Lamb had told about the flaw checked out the center's website and discovered that the vulnerabilities had only been partially fixed. "We were both pretty floored," said Lamb.

The researcher, Chris Grayson, said he, too, was able to access the same voter record database and other sensitive files in a publicly accessible directory. Grayson contacted a friend who is a professor at Kennesaw State. Two days later, the FBI was called in to investigate.

It did not bring charges against either researcher, finding no evidence of illegal entry . "At the end of the day we were doing what we thought was in the best interest of the republic—informing the parties that needed to be privy to this sort of issue," said Grayson.

The special election next Tuesday will fill the seat vacated by Republican Tom Price after he was named Health and Human Services Secretary. It has attracted national attention, including that of President Donald Trump, for whom it could be a bellwether.

First-time candidate Jon Ossoff is a Democrat with a national security background. His GOP opponent is former Georgia Secretary of State Karen Handel.

© 2017 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.