Hubble discovery of runaway star yields clues to breakup of multiple-star system

As British royal families fought the War of the Roses in the 1400s for control of England's throne, a grouping of stars was waging its own contentious skirmish—a star wars far away in the Orion Nebula.

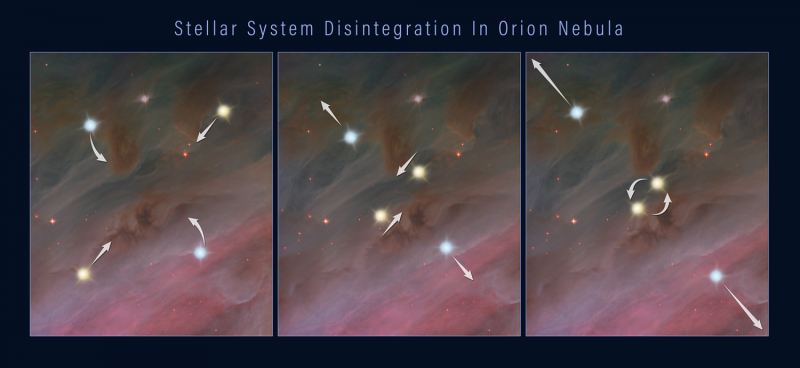

The stars were battling each other in a gravitational tussle, which ended with the system breaking apart and at least three stars being ejected in different directions. The speedy, wayward stars went unnoticed for hundreds of years until, over the past few decades, two of them were spotted in infrared and radio observations, which could penetrate the thick dust in the Orion Nebula.

The observations showed that the two stars were traveling at high speeds in opposite directions from each other. The stars' origin, however, was a mystery. Astronomers traced both stars back 540 years to the same location and suggested they were part of a now-defunct multiple-star system. But the duo's combined energy, which is propelling them outward, didn't add up. The researchers reasoned there must be at least one other culprit that robbed energy from the stellar toss-up.

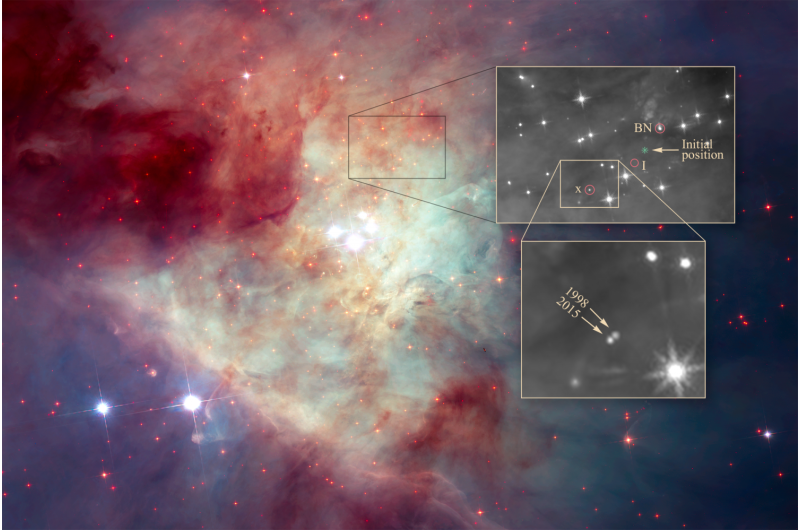

Now NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has helped astronomers find the final piece of the puzzle by nabbing a third runaway star. The astronomers followed the path of the newly found star back to the same location where the two previously known stars were located 540 years ago. The trio reside in a small region of young stars called the Kleinmann-Low Nebula, near the center of the vast Orion Nebula complex, located 1,300 light-years away.

"The new Hubble observations provide very strong evidence that the three stars were ejected from a multiple-star system," said lead researcher Kevin Luhman of Penn State University in University Park, Pennsylvania. "Astronomers had previously found a few other examples of fast-moving stars that trace back to multiple-star systems, and therefore were likely ejected. But these three stars are the youngest examples of such ejected stars. They're probably only a few hundred thousand years old. In fact, based on infrared images, the stars are still young enough to have disks of material leftover from their formation."

All three stars are moving extremely fast on their way out of the Kleinmann-Low Nebula, up to almost 30 times the speed of most of the nebula's stellar inhabitants. Based on computer simulations, astronomers predicted that these gravitational tugs-of-war should occur in young clusters, where newborn stars are crowded together. "But we haven't observed many examples, especially in very young clusters," Luhman said. "The Orion Nebula could be surrounded by additional fledging stars that were ejected from it in the past and are now streaming away into space."

The team's results will appear in the March 20, 2017 issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Luhman stumbled across the third speedy star, called "source x," while he was hunting for free-floating planets in the Orion Nebula as a member of an international team led by Massimo Robberto of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. The team used the near-infrared vision of Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 to conduct the survey. During the analysis, Luhman was comparing the new infrared images taken in 2015 with infrared observations taken in 1998 by the Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS). He noticed that source x had changed its position considerably, relative to nearby stars over the 17 years between Hubble images, indicating the star was moving fast, about 130,000 miles per hour.

The astronomer then looked at the star's previous locations, projecting its path back in time. He realized that in the 1470s source x had been near the same initial location in the Kleinmann-Low Nebula as two other runaway stars, Becklin-Neugebauer (BN) and "source I."

BN was discovered in infrared images in 1967, but its rapid motion wasn't detected until 1995, when radio observations measured the star's speed at 60,000 miles per hour. Source I is traveling roughly 22,000 miles per hour. The star had only been detected in radio observations; because it is so heavily enshrouded in dust, its visible and infrared light is largely blocked.

The three stars were most likely kicked out of their home when they engaged in a game of gravitational billiards, Luhman said. What often happens when a multiple system falls apart is that two of the member stars move close enough to each other that they merge or form a very tight binary. In either case, the event releases enough gravitational energy to propel all of the stars in the system outward. The energetic episode also produces a massive outflow of material, which is seen in the NICMOS images as fingers of matter streaming away from the location of the embedded source I star.

Future telescopes, such as the James Webb Space Telescope, will be able to observe a large swath of the Orion Nebula. By comparing images of the nebula taken by the Webb telescope with those made by Hubble years earlier, astronomers hope to identify more runaway stars from other multiple-star systems that broke apart.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and ESA (European Space Agency). NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., in Washington, D.C.

More information: "New Evidence for the Dynamical Decay of a Multiple System in the Orion Kleinmann-Low Nebula," K. L. Luhman et al., 2017 Mar. 20, Astrophysical Journal Letters iopscience.iop.org/article/10. … 847/2041-8213/aa5ff6 , arxiv.org/abs/1703.05159

Journal information: Astrophysical Journal Letters

Provided by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center