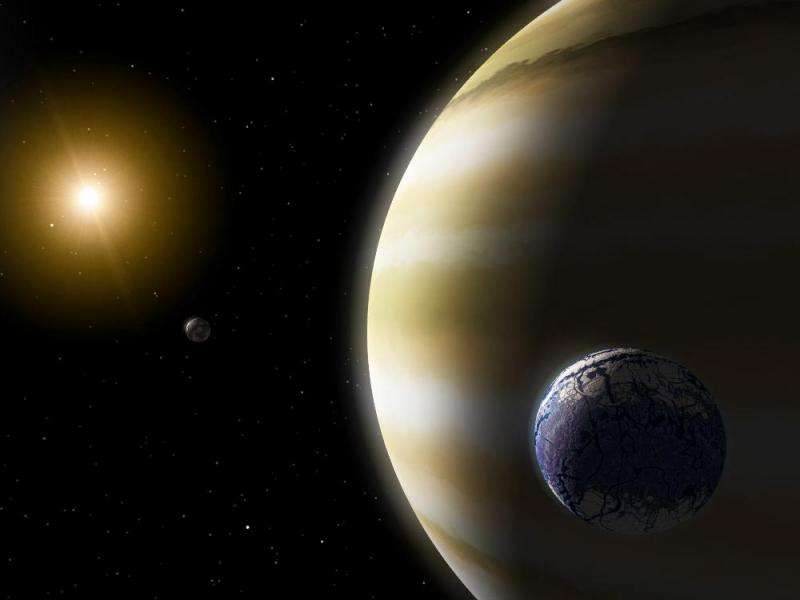

The fate of exomoons

When a star like our sun gets to be very old, after another seven billion years or so, it will shrink to a fraction of its radius and become a white dwarf star, no longer able to sustain nuclear burning. Studying the older planetary systems around white dwarfs provides clues to the long-term fate of our Sun and its planetary system. The atmosphere of a white dwarf star is expected to break up any material that accretes onto it into the constituent chemical elements and then to stratify them according to their atomic weights. The result is that the visible, uppermost layers of the atmosphere of a white dwarf should contain only a combination of hydrogen, helium (and some carbon). About one thousand white dwarf stars, however, show evidence in their spectra of pollution by some form of rocky material. This suggests that there is frequent, ongoing accretion onto these white dwarf stars of fragmentary material coming from somewhere - the precise origins are not clear.

CfA astronomers Matt Payne and Matt Holman, with two colleagues, have completed a series of simulations of the late evolution of planetary systems to try to understand where this material might be coming from. It was already known that the moons of planets can be easily knocked out of their orbits during planet-planet interactions in white dwarf systems. The question was whether these freed moons might themselves accrete onto the star to provide the polluting elements, or whether they might act to scatter asteroids towards the star. The difficulty has been the computational limits of simulating a complex evolving system that included the moons around planets.

The astronomers developed a technique of simulating the systems' evolution without moons, but then adding back the moons at a later stage in a self-consistent way. When they did so, they found that the freed moons often meandered around the inner reaches of their stellar system (well within one astronomical unit of their star), and as a consequence could either fall into the star themselves or else knock smaller asteroids, comets, or other small bodies onto the star. Thus it seems that both processes are at work. The result provides a first-look assessment of what can happen to moons once they become unbound in white dwarf systems. Future studies are planned to determine the relative importance of liberated moon material.

More information: Matthew J. Payne et al. The fate of exomoons in white dwarf planetary systems, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2017). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stw2585

Journal information: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Provided by Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics