Enceladus jets: Surprises in starlight

During a recent stargazing session, NASA's Cassini spacecraft watched a bright star pass behind the plume of gas and dust that spews from Saturn's icy moon Enceladus. At first, the data from that observation had scientists scratching their heads. What they saw didn't fit their predictions.

The observation has led to a surprising new clue about the remarkable geologic activity on Enceladus: It appears that at least some of the narrow jets that erupt from the moon's surface blast with increased fury when the moon is farther from Saturn in its orbit.

Exactly how or why that's happening is far from clear, but the observation gives theorists new possibilities to ponder about the twists and turns in the "plumbing" under the moon's frozen surface. Scientists are eager for such clues because, beneath its frozen shell of ice, Enceladus is an ocean world that might have the ingredients for life.

It's a Gas, Man

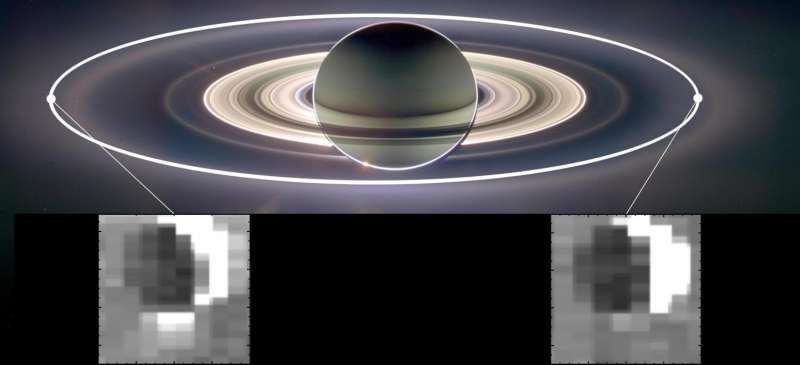

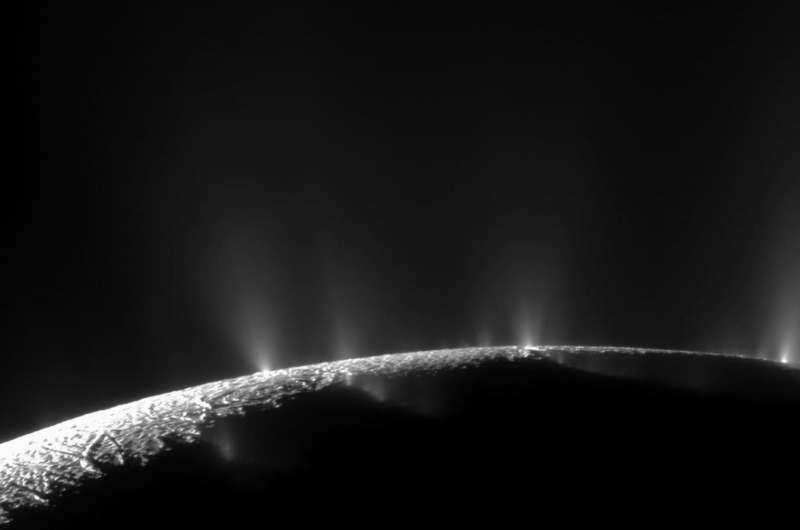

During its first few years after arriving at Saturn in 2004, Cassini discovered that Enceladus continuously spews a broad plume of gas and dust-sized ice grains from the region around its south pole. This plume extends hundreds of miles into space, and is several times the width of the small moon itself. Scores of narrow jets burst from the surface along great fractures known as "tiger stripes" and contribute to the plume. The activity is understood to originate from the moon's subsurface ocean of salty liquid water, which is venting into space.

Cassini has shown that more than 90 percent of the material in the plume is water vapor. This gas lofts dust grains into space where sunlight scatters off them, making them visible to the spacecraft's cameras. Cassini has even collected some of the particles being blasted off Enceladus and analyzed their composition.

Not the Obvious Explanation

Previous Cassini observations saw the eruptions spraying three times as much icy dust into space when Enceladus neared the farthest point in its elliptical orbit around Saturn. But until now, scientists hadn't had an opportunity to see if the gas part of the eruptions—which makes up the majority of the plume's mass—also increased at this time.

So on March 11, 2016, during a carefully planned observing run, Cassini set its gaze on Epsilon Orionis, the central star in Orion's belt. At the appointed time, Enceladus and its erupting plume glided in front of the star. Cassini's ultraviolet imaging spectrometer (or UVIS) measured how water vapor in the plume dimmed the star's ultraviolet light, revealing how much gas the plume contained. Since lots of extra dust appears at this point in the moon's orbit, scientists expected to measure a lot more gas in the plume, pushing the dust into space.

But instead of the expected huge increase in water vapor output, the UVIS instrument only saw a slight bump—just a 20 percent increase in the total amount of gas.

Cassini scientist Candy Hansen quickly set to work trying to figure out what might be going on. Hansen, a UVIS team member at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, led the planning of the observation. "We went after the most obvious explanation first, but the data told us we needed to look deeper," she said. As it turned out, looking deeper meant paying attention to what was happening closer to the moon's surface.

Hansen and her colleagues focused their attention on one jet known informally as "Baghdad I." The researchers found that while the amount of gas in the overall plume didn't change much, this particular jet was four times more active than at other times in Enceladus' orbit. Instead of supplying just 2 percent of the plume's total water vapor, as Cassini previously observed, it was now supplying 8 percent of the plume's gas.

Call a Plumber

This insight revealed something subtle, but important, according to Larry Esposito, UVIS team lead at the University of Colorado at Boulder. "We had thought the amount of water vapor in the overall plume, across the whole south polar area, was being strongly affected by tidal forces from Saturn. Instead we find that the small-scale jets are what's changing." This increase in the jets' activity is what causes more icy dust grains to be lofted into space, where Cassini's cameras can see them, Esposito said.

The new observations provide helpful constraints on what could be going on with the underground plumbing—cracks and fissures through which water from the moon's potentially habitable subsurface ocean is making its way into space.

With the new Cassini data, Hansen is ready to toss the ball to the theoreticians. "Since we can only see what's going on above the surface, at the end of the day, it's up to the modelers to take this data and figure out what's going on underground."