December 3, 2015 report

Magnetic invisibility cloak shields magnets from magnetic fields

(Phys.org)—Typically when two magnets are brought close together, they either attract or repel each other due to interactions between their magnetic fields. In a new study, researchers have designed a 3D magnetic invisibility cloak, inside of which they placed a magnetic object, and showed that the cloaked magnet is no longer affected by nearby magnetic fields. It appears as if the cloaked magnet has become demagnetized, but in reality the magnet is simply hidden.

The researchers, led by Yungui Ma at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China, have published a paper titled "Three-dimensional magnetic cloak working from d.c. to 250 kHz" in a recent issue of Nature Communications. Like other invisibility cloaks, the new cloak is made of metamaterials (man-made materials with repeating patterns) and works by manipulating electromagnetic waves in unusual ways.

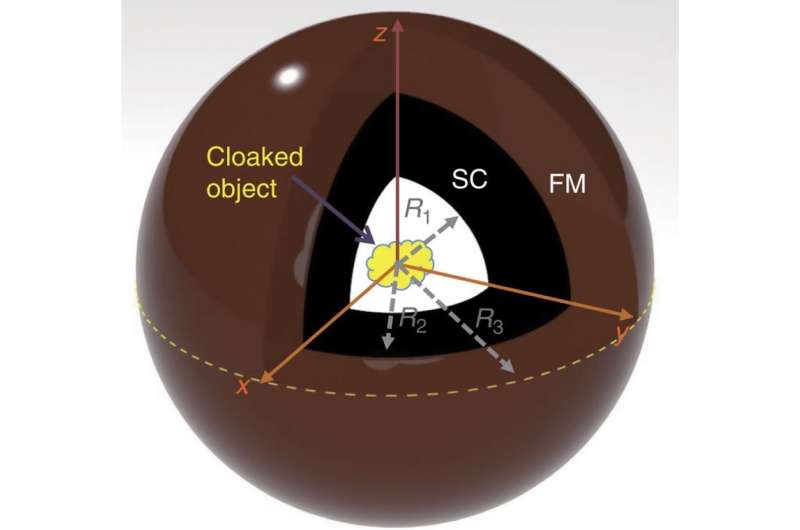

To achieve the cloaking effect, the researchers used a new type of invisibility cloak called a bilayer cloak, first demonstrated in 2012 by Alvaro Sanchez and colleagues at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. The cloak has a spherical structure consisting of two shells: a superconducting inner shell (made of single-crystal YBCO) and a ferromagnetic outer shell (made of a nickel zinc composite).

These two materials have opposite magnetic behaviors, which causes them to have opposite effects on an external magnetic field: the inner YBCO shell expels the magnetic field, while the outer nickel zinc shell concentrates it. By carefully machining, etching, fine-tuning, and combining these materials, the researchers were able to completely cancel out the opposing effects, inducing the magnetic transparency effect.

"In an optimum state, these two counteractions (expelling and attracting) can be totally balanced so that their combination will have no disturbance on the external magnetic field at low frequencies," Ma told Phys.org.

The magnetic invisibility cloak could have applications in biological experiments and magnetically sensitive equipment, as it could protect living organisms and other objects from magnetic fields while allowing the magnetic fields to pass undistorted around the objects. It could also be used as an "anti-probe technology" to allow magnetic or metallic objects to pass through metal detectors without setting them off.

However, the researchers caution that the current design is still far from the application stage. The biggest problem is that the superconductor YBCO must be cooled in liquid nitrogen to around 90 K for the cloak to function. The researchers are working on this problem, among others.

"In addition, we are not clear how the cloaking effect will become when the probing (or incident) field becomes very inhomogeneous spatially," Ma said. "In our theory, we have assumed a uniform incident field."

Despite these challenges, the new cloak still looks promising for commercial applications.

"Their article is a nice extension of our works on magnetic cloaks," said Sanchez, who was not affiliated with this study. "Their work represents another demonstration that d.c. and low-frequency regions of the electromagnetic spectrum may be some of the best cases for actual applications of cloaks. Because static and low-frequency magnetic fields are crucial in many technologies, from medicine to information technology to security, the magnetic cloaking results may have important applications in actual technologies."

More information: Jianfei Zhu, et al. "Three-dimensional magnetic cloak working from d.c. to 250 kHz." Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms9931

Journal information: Nature Communications

© 2015 Phys.org