Understanding collective animal behavior may be in the eye of the computer

No machine is better at recognizing patterns in nature than the human brain. It takes mere seconds to recognize the order in a flock of birds flying in formation, schooling fish, or an army of a million marching ants. But computer analyses of collective animal behavior are limited by the need for constant tracking and measurement data for each individual; hence, the mechanics of social animal interaction are not fully understood.

An international team of researchers led by Maurizio Porfiri, associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at NYU Polytechnic School of Engineering, has introduced a new paradigm in the study of social behavior in animal species, including humans. Their work is the first to successfully apply machine learning toward understanding collective animal behavior from raw data such as video, image or sound, without tracking each individual. The findings stand to significantly impact the field of ethology— the objective study of animal behavior—and may prove as profound as the breakthroughs that allowed robots to learn to recognize obstacles and navigate their environment. The paper was published online today in Scientific Reports.

Starting with the premise that humans have the innate ability to recognize behavior patterns almost subconsciously, the researchers created a framework to apply that instinctive understanding to machine learning techniques. Machine learning algorithms are widely used in applications like biometric identification systems and weather trend data, and allow researchers to understand and compare complex sets of data through simple visual representations.

A human viewing a flock of flying birds discerns both the coordinated behavior and the formation's shape—a line, for example—without measuring and plotting a dizzying number of coordinates for each bird. For these experiments, the researchers deployed an existing machine learning method called isometric mapping (ISOMAP) to determine if the algorithm could analyze video of that same flock of birds, register the aligned motion, and embed the information on a low-dimensional manifold to visually display the properties of the group's behavior. Thus, a high-dimensional quantitative data set would be represented in a single dimension—a line—mirroring human observation and indicating a high degree of organization within the group.

"We wanted to put ISOMAP to the test alongside human observation," Porfiri explained. "If humans and computers could observe social animal species and arrive at similar characterizations of their behavior, we would have a dramatically better quantitative tool for exploring collective animal behavior than anything we've seen," he said.

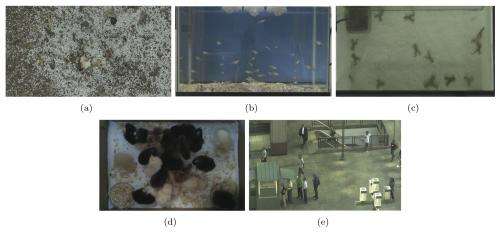

The team captured video of five social species—ants, fish, frogs, chickens, and humans—under three sets of conditions—natural motion, and the presence of one and two stimuli—over 10 days. They subjected the raw video to analysis through ISOMAP, producing manifolds representing the groups' behavior and motion. The researchers then tasked a group of observers with watching the videos and assigning a measure of collective behavior to each group under each circumstance. Human rankings were scaled to be visually comparable with the ISOMAP manifolds.

The similarities between the human and machine classifications were remarkable. ISOMAP proved capable not only of accurately ascribing a degree of collective interaction that meshed with human observation, but of distinguishing between species. Both humans and ISOMAP ascribed the highest degree of interaction to ants and the least to frogs—analyses that hold true to known qualities of the species. Both were also able to distinguish changes in the animals' collective behavior in the presence of various stimuli.

The researchers believe that this breakthrough is the beginning of an entirely new way of understanding and comparing the behaviors of social animals. Future experiments will focus on expanding the technique to more subtle aspects of collective behavior; for example, the chirping of crickets or synchronized flashing of fireflies.

Journal information: Scientific Reports

Provided by New York University