The Red Queen was right: We have to run to keep in place

Biologists quote Lewis Carroll when arguing that survival is a constant struggle to adapt and evolve. Is that true, or do groups die out because they experience a run of bad luck? Charles Marshall and Tiago Quental of UC Berkeley tested these hypotheses using mammals that arose and died out (or are now dying out) in the past 66 million years, and found that it's not luck but failure to adapt to a deteriorating environment.

The death of individual species is not the only concern for biologists worried about groups of animals, such as frogs or the "big cats," going extinct. University of California, Berkeley, researchers have found that lack of new emerging species also contributes to extinction.

"Virtually no biologist thinks about the failure to originate as being a major factor in the long term causes of extinction," said Charles Marshall, director of the UC Berkeley Museum of Paleontology and professor of integrative biology. "But we found that a decrease in the origin of new species is just as important as increased extinction rate in driving mammals to extinction."

The results apply to slow change over millions of years, Marshall cautions, not rapid global change like Earth is now experiencing from human activities. Yet the findings should help biologists understand the pressures on today's flora and fauna and what drove evolution and extinction in the past, he said.

The results, published June 20 in Science Express, come from a study of 19 groups of mammals either extinct or, in the case of horses, elephants, rhinos, and others, are in decline from a past peak in diversity. All are richly represented in the fossil record and had their origins sometime in the last 66 million years, during the Cenozoic Era.

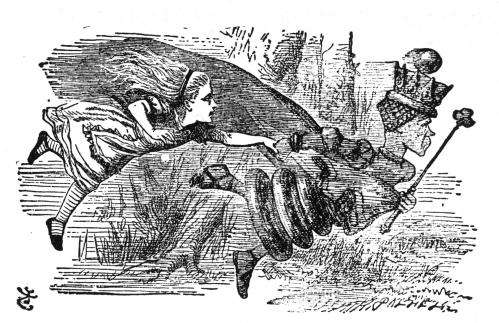

The study was designed to test a popular evolutionary theory called the Red Queen hypothesis, named after Lewis Carroll's character who in "Through the Looking Glass" described her country as a place where "it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place."

In biology, this means that animals and plants don't just disappear because of bad luck in a static and unchanging environment, like a gambler losing it all to a run of bad luck at the slot machines. Instead, they face constant change – a deteriorating environment and more successful competitors and predators – that requires them to continually adapt and evolve new species just to survive.

Though the specific cause of declining originations and rising extinctions for these groups is unclear, the researchers concluded that their demise was not just dumb luck.

"Each group has either lost, or is losing, to an increasingly difficult environment," Marshall said. "These groups' demise was at least in part due to the loss to the Red Queen, that is, a failure to keep pace with a deteriorating environment."

Marshall and former post-doctoral fellow Tiago Quental found that the groups were initially driven to higher diversity until they reached the carrying capacity of their environment, that is, the maximum number of species their environment can hold, after which their environment deteriorated to the point where there was too much diversity to be sustained, leading to their extinction.

"In fact our data suggest that biological systems may never be in equilibrium at all, with groups expanding and contracting under persistent and rather, geologically speaking, rapid change" he said.

Marshall and Quental, now at the University of Sao Paolo, Brazil, will present their results in two talks on Saturday, June 22, at the Evolution 2013 meeting in Snowbird, Utah.

More information: "How the Red Queen Drives Terrestrial Mammals to Extinction," by T.B. Quental et al. Science Express, 2013.

Journal information: Science Express

Provided by University of California - Berkeley