April 25, 2013 report

Optical magnetic microscope for high-resolution, wide-field cell imaging

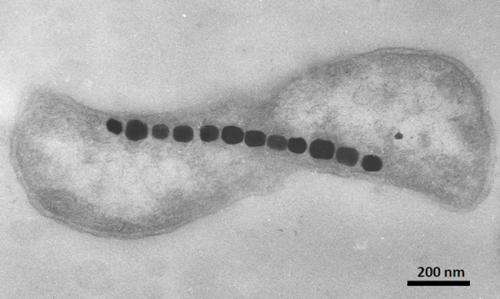

(Phys.org) —Nano-sized crystals of magnetic material can be found in a wide variety of organisms. Among the most studied are magnetotactic bacteria, which can orient and navigate using biosynthesized magnetosomes. These organelles are made from iron oxide or iron sulphide particles and may eventually have many therapeutic applications. When used in conjunction with new MRI-based methods, they can potentially be used as contrast agents or magnetic labels in imaging, or for drug delivery and local hyperthermic heating in treatment. A better understanding of how these magnetosomes are biomineralized, and how the three-dimensional fields that originate from them are structured is essential to achieve these goals. A new report this week in Nature describes an optical magnetic imaging technique that can be used to map magnetic field variations on the nanoscale. The author's wide-field microscopy technique allows parallel optical and magnetic imaging of many individual cells across a field of 100 microns or more.

The general principles of the magnetic imaging technique used here have been known for some time. The basic concept is to detect changes in the quantum spin states of crystallographic defects, known as nitrogen-vacancy centers, within a diamond chip. The new Nature study is the first to do this for a living creature. The rig put together by the authors is probably one of the more complicated sets of probing devices you are likely ever to see. The bacteria sit above the diamond surface, where the fields from the magnetosomes affect characteristic signals (electron spin resonances) of the nitrogen-vacancy centers. An optical beam is used to readout those signals, and the vector components in each direction of the magnetic field can later be reconstructed.

The strain of bacteria used was Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1, which forms cubo-octahedral magnetic particles roughly 50 nm in diameter. The fields produced by these bacteria could be imaged to a resolution of 400nm. The optical images of the field distributions were collected using a sCMOS camera across a field of view 100um by 30um. Bright field images were concurrently acquired using 660nm red LED back-illumination to link cell features with the magnetic patterns. Fluorescence excitation to asses bacterial viability was done through the microscope objective using 470nm illumination.

In addition to the geometrical tangle of all the required optical elements, the setup also needed to incorporate a permanent magnetic field for proper operation. This which applied by a nearby permanent magnet. The final element necessary was the appropriate application of microwave energy. The microwaves were applied to the diamond surface from an overlying wire connected to the output of a synthesizer.

Beyond just taking snapshots of field distributions, the setup also has the potential for dynamic imaging of field changes across the development cycle of the magnetosome crystals. Other magnetic imaging techniques, like SQUID and electron holography, might eventually be similarly adapted to yield even higher spatial resolutions then the techniques used here.

More information: Optical magnetic imaging of living cells, Nature 496, 486–489 (25 April 2013) doi:10.1038/nature12072

Abstract

Magnetic imaging is a powerful tool for probing biological and physical systems. However, existing techniques either have poor spatial resolution compared to optical microscopy and are hence not generally applicable to imaging of sub-cellular structure (for example, magnetic resonance imaging), or entail operating conditions that preclude application to living biological samples while providing submicrometre resolution (for example, scanning superconducting quantum interference device microscopy, electron holography and magnetic resonance force microscopy). Here we demonstrate magnetic imaging of living cells (magnetotactic bacteria) under ambient laboratory conditions and with sub-cellular spatial resolution (400 nanometres), using an optically detected magnetic field imaging array consisting of a nanometre-scale layer of nitrogen–vacancy colour centres implanted at the surface of a diamond chip. With the bacteria placed on the diamond surface, we optically probe the nitrogen–vacancy quantum spin states and rapidly reconstruct images of the vector components of the magnetic field created by chains of magnetic nanoparticles (magnetosomes) produced in the bacteria. We also spatially correlate these magnetic field maps with optical images acquired in the same apparatus. Wide-field microscopy allows parallel optical and magnetic imaging of multiple cells in a population with submicrometre resolution and a field of view in excess of 100 micrometres. Scanning electron microscope images of the bacteria confirm that the correlated optical and magnetic images can be used to locate and characterize the magnetosomes in each bacterium. Our results provide a new capability for imaging bio-magnetic structures in living cells under ambient conditions with high spatial resolution, and will enable the mapping of a wide range of magnetic signals within cells and cellular networks.

Commentary: Magnetic bacteria on a diamond plate, Mihály Pósfai & Rafal E. Dunin-Borkowski, Nature 496, 442–443 (25 April 2013) doi:10.1038/496442a

Journal information: Nature

© 2013 Phys.org