Doha climate talks open amid warnings of calamity

Nearly 200 nations gather in Doha from Monday for a new round of climate talks as a rush of reports warn extreme weather events like superstorm Sandy may become commonplace if mitigation efforts fail.

Negotiators will converge in the Qatari capital for two weeks under the UN banner to review commitments to cutting climate-altering greenhouse gas emissions.

Ramping up the pressure, expert reports warned in recent days that existing mitigation pledges are not nearly enough to limit warming to a manageable 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 deg Fahrenheit) from pre-industrial levels.

"A faster response to climate change is necessary and possible," UN climate chief Christiana Figueres said ahead of the talks.

"Doha must make sure the response is accelerated."

The UN Environmental Programme said this week the goal of keeping planet warming in check has moved further out of reach and the world was headed for an average 3-5 deg C temperature rise this century barring urgent action.

And the World Bank said a planet that is four degrees warmer would see coastal areas inundated and small islands washed away, food production slashed, species eradicated, more frequent heat waves and high-intensity cyclones, and diseases spread to new areas.

"Time is clearly not on our side," Marlene Moses, chairwoman of the Alliance of Small Island States told AFP.

Topping the agenda in Doha is the launch of a followup commitment period for the Kyoto Protocol, the world's only binding pact for curbing greenhouse gas emissions.

Delegates must also set out a work plan for arriving in the next 36 months at a new, global climate deal that must enter into force by 2020.

Negotiators will be under pressure to raise pre-2020 emission reduction targets, and rich nations to come up with funding for the developing world's mitigation actions.

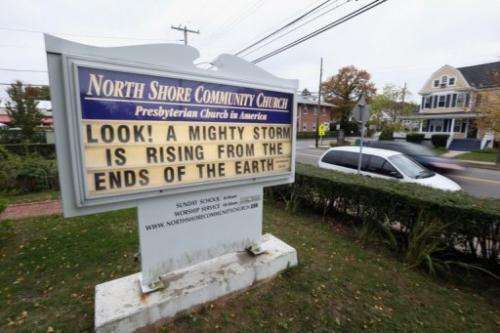

The planet has witnessed record-breaking temperatures in the past decade and frequent natural disasters that some blame on climate change—recently superstorm Sandy which ravaged Haiti and the US east coast.

Yet countries disagree on several issues, including the duration of a "second commitment period" for the Kyoto Protocol, which binds about 40 rich nations and the EU to an average five percent greenhouse gas reduction from 1990-levels.

That commitment runs out on December 31.

The EU, Australia and some small Kyoto parties have said they would take on commitments in a followup period, but New Zealand, Canada, Japan and Russia will not.

Small island countries under the most imminent threat of warming-induced sea level rises, demand a five-year followup period, believing this will better reflect the urgency.

The EU and others want an eight-year period flowing over into the 2020 deal.

Poor countries also want rich states to raise their pledges to curb warming gases, including the EU from 20 from 30 percent.

"The biggest historical emitters have a responsibility to do more, much more, than they have to date," said Moses.

The developed world has already agreed to boost funding for the developing world's climate plans to a level of $100 billion a year from 2020—up from a total $30 billion over the period 2010-2012.

But no numbers have been decided for the interim, nor is it clear where the new money will come from.

"If no agreement is achieved in Doha, we will enter 2013... with no support to help many developing coutries in reducing their emissions," said Wael Hmaidan, director of the NGO Climate Action Network.f

Delegates will be joined by more than 100 government ministers for the final four days of talks, notorious for dragging out way past their programmed close as negotiators hold out to the last in a poker-like standoff.

"Doha... will send important signals about whether the world can still manage to keep warming within tolerable limits, or if we are headed for severe climate chaos," said Kelly Rigg, executive director of the Global Campaign for Climate Actions.

Climate change in numbers

Following is a snapshot of the science numbers that will inform the November 26-December 7 UN climate talks in Doha, Qatar.

— The global average temperature has risen 0.74 degrees Celsius (1.3 deg Fahrenheit) in the century to 2005, according to a benchmark 2007 report of the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

— The decade 2001-2010 was the hottest since records began in 1850, says the World Meteorological Organisation. 2011 was the hottest year.

— Most scientists believe the main culprit is greenhouse gas released by burning fossil fuel, trapping solar heat in the atmosphere.

— The IPCC, which is to bring out a new, updated report in 2013/14, has predicted further warming of between 1.1 deg C and 6.4 deg C by 2100 from 1980-1999 levels—depending on greenhouse gas emission levels.

— UN countries agreed in Copenhagen in 2009 to reduce greenhouse gas pollution to limit warming to 2 deg C from pre-industrial levels.

— The UN Environmental Programme said Wednesday that that goal has moved further out of reach and temperatures will rise by 3-5 deg C on current reduction pledges.

— The WMO says greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere reached record concentrations in 2011, and reported Tuesday a 30 percent increase in "radiative forcing"—the warming effect on climate, between 1990 and 2011.

— Since the start of the industrial age in about 1750, some 375 billion tonnes of carbon have been released into the atmosphere and will stay there for centuries, according to the WMO.

— Scientists say climate change is already visible in sea-level rise, loss of alpine glaciers and snow cover, shrinking Arctic summer sea ice, thawing permafrost, poleward migration of animals and plants and an increase in intense tropical cyclone activity in the North Atlantic.

— The planet has witnessed a rise in extreme weather events in the past decade that some have blamed on climate change—prolonged droughts, heat waves and torrential storms—recently superstorm Sandy which ravaged Haiti and the US east coast.

— The trend is likely to continue, and the IPCC predicts that 20-30 percent of plant and animal species will risk extinction once temperatures rise by 1.5-2.5 deg C from 1980-99 levels (IPCC)

— Up to 250 million people in Africa may be exposed to water stress due to climate change by 2020, and crop yields could be slashed in half in some countries.

— A global temperature rise of 3-4 deg C could displace more than 300 million people through sea level rise and flooding—inundating coastal cities and small islands, according to UN figures.

— The IPCC has predicted that sea levels will rise by between 18 and 59 cm by 2100, but some scientists say a surge in Antarctic and Greenland ice sheet melt could boost levels by as much as a metre (38 inches).

— In September, US scientists said Arctic sea ice has shrunk to its smallest surface area since record-keeping began.

(c) 2012 AFP