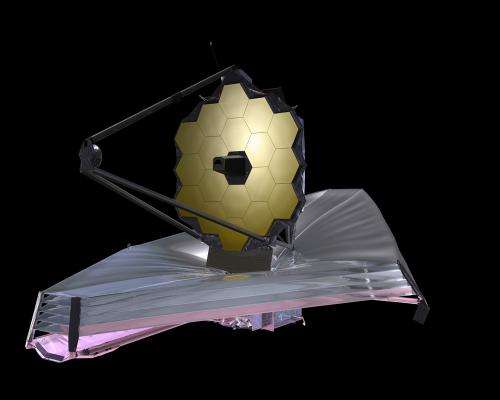

Tests under way on the sunshield for Webb telescope

NASA is testing an element of the sunshield that will protect the James Webb Space Telescope's mirrors and instruments during its mission to observe the most distant objects in the universe.

The sunshield will consist of five tennis court-sized layers to allow the Webb telescope to cool to its cryogenic operating temperature of minus 387.7 degrees Fahrenheit (40 Kelvin).

Testing began early this month at ManTech International Corp.'s Nexolve facility in Huntsville, Ala., using flight-like material for the sunshield, a full-scale test frame and hardware attachments. The test sunshield layer is made of Kapton, a very thin, high-performance plastic with a reflective metallic coating, similar to a Mylar balloon. Each sunshield layer is less than half the thickness of a sheet of paper. It is stitched together like a quilt from more than 52 individual pieces because manufacturers do not make Kapton sheets as big as a tennis court.

The tests are expected to be completed in two weeks.

"The conclusion of testing on this full size layer will be the final step of the sunshield's development program and provides the confidence and experience to manufacture the five flight layers," said Keith Parrish, Webb Sunshield manager at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

During testing, engineers use a high-precision laser radar to measure the layer every few inches at room temperature and pressure, creating a 3D map of the material surface, which is curved in multiple directions. The map will be compared to computer models to see if the material behaved as predicted, and whether critical clearances with adjacent hardware are achieved.

The test will be done on all five layers to give engineers a precise idea of how the entire sunshield will behave once in orbit. Last year, a one-third-scale model of the sunshield was tested in a chamber that simulated the extreme temperatures it will experience in space. The test confirmed the sunshield will allow the telescope to cool to its operating temperature.

After the full-size sunshield layers complete testing and model analysis, they will be sent to Northrop Grumman in Redondo Beach Calif., where engineers verify the process of how the layers will unfurl in space. There the sunshield layers will be folded, much like a parachute, so they can be safely stowed for launch.

Provided by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center