How a protein communicates across long-distances

Cutting out a short part of a protein can lead to strong movements at a distant functional site. This provides a clear example of how the network of interactions inside of a protein can give rise to long-range communication. The discovery, made by an international team of researchers, is published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

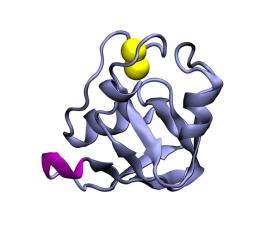

The researchers studied ferredoxin, a class of proteins crucial to photosynthesis, the process by which plants use the energy contained in sunlight to bind carbon dioxide from our atmosphere.

“While the focus of our work are molecular properties of ferredoxin, the fascinating fact about basic research is that it might always lead to novel and sometimes unforeseen future applications. For example, more knowledge about these proteins may give new strategies for renewable energy production. We hope that our findings about how communication works inside a protein will provide guiding principles about designing molecular devices in, for instance, artificial photosynthesis,” says one of the authors Alexander Schug, researcher at the Department of Chemistry, Umea University.

The researchers found experimentally that cutting out a short part of a Fdx protein leads to a mutated protein with minimal changes in its structure and stability that keeps its function at lower temperatures. At physiological higher temperatures, however, the mutated protein suddenly loses its function while the native protein (i.e. lacking the mutation) does not. To explain this phenomenon, a theoretical investigation supported by computer simulations was performed. It revealed that the cut leads to strong movements at a distant functional site. Further, the ability to “flip” this functional switch in the protein was shown to arise from from long-range communication by a network of many short-range interactions.

Proteins are molecular components that compose a large portion of the machinery of the cell. They are indispensible, and they carry out many important biological tasks, ranging from muscle movement to oxygen transport in the blood stream. Therefore, understanding the physical principles that allow these building blocks to perform high-level functions in the cell is an important task for both basic science and medical research. Typically, a protein changes its shape, or structure, at a large scale during its functional cycle.

In the current work, the researchers found that the iron-sulfur binding ferredoxin (Fdx) proteins do not require such shape-changes for controlling its function. Instead, distant locations on the protein can communicate by a network of short-ranged interactions. Fdx proteins are crucial for photosynthesis, e.g. the process by which plants use the energy contained in sunlight to bind carbon dioxide from our atmosphere. Therefore understanding their dynamics is central to understanding cellular life and it may provide new strategies for renewable energy production.

More information: The study appears as “Allostery in the ferredoxin protein motif does not involve a conformational switch” in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). It is a result of an international collaboration.

Provided by Umea University