New study fuels Louisiana subsidence controversy

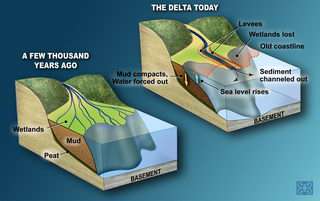

While erosion and wetland loss are huge problems along Louisiana's coast, the basement 30 to 50 feet beneath much of the Mississippi Delta has been highly stable for the past 8000 years with negligible subsidence rates. So say geoscientists from Tulane University and Utrecht University, challenging the notion that tectonic subsidence bears much of the blame for Louisiana's coastal geologic problems.

Research by a team led by Torbjörn Törnqvist of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Tulane University, suggests the main cause of subsidence is compaction of the shallowest and most recent delta sediments. Their findings are reported in the August issue of Geology, published by the Geological Society of America.

According to Törnqvist, rapid subsidence of coastal Louisiana is well documented but primary drivers of the subsidence are not well understood. Leading candidates include:

-- Long-term subsidence and faulting of the Earth's crust caused by rapidly accumulating sediments in the Mississippi Delta.

-- Compaction of relatively shallow and water-rich deposits formed during the past 10,000 years.

-- Withdrawal of oil, gas, and groundwater from the subsurface.

According to Törnqvist, current controversies center on the relative importance of long-term subsidence of the crust. The role of tectonic processes and their relationship to sea-level rise, coastal erosion, and wetland loss have received considerable attention from researchers. Recent studies have suggested rates of subsidence of the Mississippi Delta basement of 10 millimeters per year or more.

"If this is the whole story," says Törnqvist, "there would be major consequences for Louisiana, because subsidence of Earth's crust is a fundamentally natural process that remains entirely beyond human control."

With funding mainly from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Törnqvist and his team took a different approach, reconstructing the rate of sea-level rise over the past 8000 years from three separate areas in the Mississippi Delta. Peat samples were used as sea-level indicators. According to Törnqvist, peat formation begins as soon as water levels rise above the land surface.

Carbon isotope analyses provided verification that accumulation of the samples was directly controlled by sea-level rise. Determining precise elevation of sampling sites was accomplished with a combination of GPS measurements and optical surveying.

"Since global sea-level change would affect each of our locations in a similar way, we attributed any differences to differential motions of the basement underneath," said Törnqvist.

The team then compared its results with sea-level data spanning the same time period from areas in the Caribbean regarded as tectonically stable, including Florida and the Bahamas. Törnqvist and his colleagues were surprised to find no difference, suggesting that large portions of the delta basement are stable. They also inferred from the data that long-term subsidence rates are more on the order of a fraction of a millimeter per year rather than 10 millimeters.

Törnqvist points out that these numbers do not necessarily apply to the entire delta. He also notes that well-documented high-subsidence rates in and near the birdfoot of the delta indicate that different conditions prevail there. "It remains to be demonstrated how rapidly the basement under metropolitan New Orleans subsides," he said.

According to H. Richard Lane, Program Director of NSF's sedimentary geology and paleobiology program, the study's imaginative approach is timely and a step in the right direction. "If we are to reverse the loss of Louisiana wetlands and the protection they afford New Orleans, we must think outside the box. These scientists demonstrate that innovative research can open many new possibilities for addressing environmental issues," Lane said.

Törnqvist is convinced the study illustrates the dangers of incomplete understanding of subsidence processes. "Our research could have major implications for rebuilding plans that are currently being debated," he said. "Over the long term, comprehensive understanding of subsidence will better support rational coastal management and successful urban and land-use planning for all low-lying areas along the Gulf Coast."

Source: National Science Foundation