How a system that made elephants half-captive likely ensured their survival

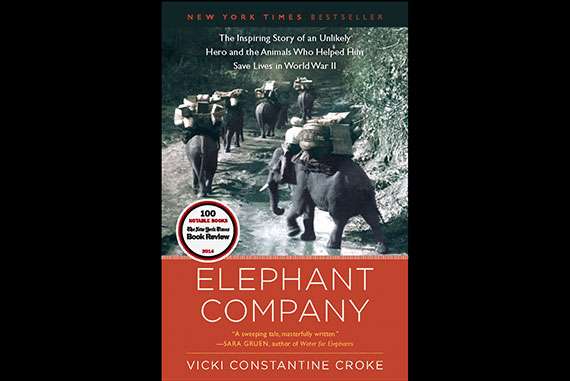

Author Vicki Croke knows her elephants. A regular contributor to National Public Radio's "Here & Now" and co-host of "The Wild Life" on WBUR, Croke is the author of the New York Times best-seller "Elephant Company." She discusses how, paradoxically, the giant pachyderms' labor for humans has helped to save them in the wild.

Croke, who also is author of "The Lady and the Panda," discussed her work and her findings in a question-and-answer session with the Gazette.

GAZETTE: How did you come to write about the elephants of Myanmar, or Burma, as it was formerly known?

CROKE: I fell in love with the story of J.H. "Billy" Williams, who came to Burma in 1920 for the love of elephants. He spent his life working with elephants and working for more humane care for these elephants, the logging elephants of Burma. As it turns out, this whole system that they have in place saved their lives, as elephants vanished from some of the countries around Myanmar.

GAZETTE: What is the Myanmar system, and how did it save the elephants?

CROKE: Each elephant who worked moving logs had his own uzi—elephant handler. They would work together for their whole lives. Elephant life spans are roughly the same as ours. These guys knew and really loved their elephants. The elephants would work in the morning for four to six hours, dragging and pushing [teak] logs that had been cut down, bringing them to dry creek beds to wait for the monsoons to bring them down. And in the afternoons, the uzis would bring their elephants to a river to be bathed, and the elephants, who wore teak bells around their neck, would be released in the forest. They'd mingle with wild elephants. Elephants only sleep a couple of hours a day, so the majority of their day was spent as wild elephants. They didn't go far. They didn't need to, and in the morning, the uzis would follow their tracks. They could tell their own elephants' track, and listen for the bells—they made their bells so each was unique—and call them back for the morning work.

GAZETTE: And having an economic function has saved the elephant?

CROKE: Yes. In India, unemployed elephants are begging on the city streets with their mahouts [handlers]. Myanmar has the second-largest population of Asian elephants in the world, and the largest population of captive elephants in the world. Now, as Myanmar is opening up, a whole bunch of conservation groups are rushing in there. What will become of the elephants in Myanmar is an open question, with multinational corporations coming in.

GAZETTE: What was Williams' role in this?

CROKE: There was a process called "kheddaring." They would capture and break young elephants for work: starve them and beat them into submission. When they were heartbroken, then they'd be trained for work in the logging camps. Williams met a master mahout named Po Toke, who thought this system was ridiculous. He had raised a young elephant, named Bandoola, and he said, 'Look, if you raise a baby, they're much more reliable. You don't have to be cruel.' And so Williams, because he was the Englishman [and that had clout in colonial Burma], got to establish a kind elephant school.

In addition, he was an elephant whisperer and a really skilled elephant doctor. [After the daily bath,] Williams would check each elephant for their health. Each elephant had his own ongoing biography, and he'd make notes in each elephant's logbook about how each was doing.

GAZETTE: It would be a shame to mess up a system that has lasted decades.

CROKE: It would be a shame if forests were clear-cut, and the elephants lost their home and the work that has made them valuable enough to people to protect them. But it would be wonderful if the elephants there were saved even without having to have a day job.

GAZETTE: What's the most fun thing you learned writing "Elephant Company"?

CROKE: When the elephants would get caught by their uzis, they knew what was happening. But if they were eating something particularly good—if they'd gotten into a rice paddy or a pineapple grove—they would stuff their bells with mud to silence them.

GAZETTE: And the most surprising?

CROKE: I knew that what Williams did in Burma made life better for working elephants, but what I found out in researching the book is that the system that he helped refine basically saved the elephants of Myanmar. It's amazing to me that what seems counterintuitive—having these beautiful wild creatures in chains for part of the day—turned out to be their salvation, even now.

Provided by Harvard University

This story is published courtesy of the Harvard Gazette, Harvard University's official newspaper. For additional university news, visit Harvard.edu.