Did Richard III manage to keep his scoliosis a secret up until his death in 1485?

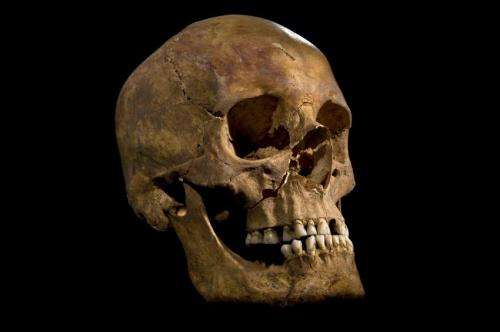

Last month saw the mortal remains of King Richard III reinterred at Leicester Cathedral, more than two years after University of Leicester archaeologists discovered his skeleton in a car park in August 2012.

The body of a mediaeval monarch was always under scrutiny, and Richard III's was no exception. In death, however, his body became subject to new forms of examination and interpretation: stripped naked after the Battle of Bosworth, his corpse was carried to Leicester and exhibited before being buried.

The discovery of his skeleton, which had severe scoliosis, and the physical truth it reveals about the historical Richard, has prompted further consideration of those undepicted scenes from his life.

No mention of Richard's distinctive physique survives from during his lifetime, perhaps out of respect to a reigning monarch, or perhaps because he hid it so well.

In a new study published in Medical Humanities this month (April), Dr Mary Ann Lund, of the University of Leicester's School of English, argues that as with all monarchs Richard's body image in life was carefully controlled and he probably kept any signs of his scoliosis hidden outside of the royal household - up until his death.

Dr Lund said: "It is highly likely that Richard took care to control his public image. The body of the king was part of the propaganda of power, and even when it was revealed in order to be anointed as part of his coronation ceremony it was simultaneously concealed from the congregation.

"Tailoring probably kept the signs of his scoliosis hidden to spectators outside the royal household of attendants, servants and medical staff who dressed, bathed and tended to the monarch's body."

The stripping of Richard's corpse at Bosworth in 1485 made his physical shape noticeable to many hundreds of witnesses, perhaps for the first time.

In the paper, 'Richard's back: death, scoliosis and myth making', Dr Lund considers how the treatment of Richard's dead body after the Battle of Bosworth is related to his later historical and literary reputation as 'Crookback Richard'.

Richard's body came to be notorious for its misshapen appearance during the Tudor period, although until the discovery of his body it was never clear whether this was pure fabrication to render accounts of his character and actions all the more extreme.

In Richard's case, this purported link between physique and character was frequently underlined, and as the Tudor regime became established, his image became more distorted -he gained a withered arm and unequal limbs, none of which were evident on the skeleton- to fit his blackened reputation.

Shakespeare's history plays make much of Richard's physique - portraying his character as deformed and explicitly hunchbacked. In Henry VI, Part 3, he claims that nature made 'an envious mountain on my back/Where sits deformity to mock my body' while in Richard III, Queen Elizabeth calls him 'that foul bunch-backed toad'.

Dr Lund added: "Stage history has reincarnated Richard as monster, villain and clown, but recent events have helped us to re-evaluate these physically defined depictions and strip back the cultural accretions that have surrounded his body.

"The care he in all probability received for his scoliosis from his surgically trained physician was large in scale: traction and manual manipulation needed specially designed equipment, space and assistants. Yet, it may have been only a relatively small group of people in Richard's trusted circle who knew of his condition. The absence of contemporary testimony does not prove this, however.

"What is certain is that, after his death, the exposure of Richard's body went beyond the two days of its exhibition in Leicester. That moment after Bosworth inaugurated a longer and more brutalising process, in which an ever-more twisted physique was revealed to the public eye, his own body becoming deployed as a major tactic in the rhetorical strategy against him. When Shakespeare's Richard boasts of his shape-changing potential, he registers too the bending course of history and myth making."

More information

Medical Humanities , DOI: 10.1136/medhum-2014-010647

Provided by University of Leicester