Researchers document disaster recovery in and around Fukushima

Since the earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan in 2011, Yoh Kawano's heart and mind have been set on venturing into the contaminated ruins of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

Recently, he achieved his goal. What he learned could help when the next disaster hits.

Kawano, a 43-year-old UCLA staffer and native of Japan, with a background in urban planning, mapping technology and the humanities, needed to see for himself the site where three nuclear reactors exploded. He wanted to observe the massive cleanup effort and learn why workers choose to spend day after day inside what Time Magazine recently called "the world's most dangerous room."

Kawano is a geographic information systems coordinator for the UCLA Institute of Digital Research and Education. He teaches students in the UCLA Urban Humanities Initiative program how to create data-rich computerized maps. He and UCLA GIS researcher Arfakhashad Munaim, 29, were given access to Fukushima during a trip to the disaster-stricken region in December.

Their mission, funded largely by a grant from the UCLA Urban Humanities Initiative, was to take photos, record videos and interview victims and government officials to document the recovery in the area where a 9.0 magnitude earthquake, tsunami and nuclear radiation forced thousands of people to evacuate. Since returning to UCLA, Kawano and Munaim have worked on mapping the data in a way that will allow scholars, governments and relief organizations to visualize the recovery progress. They hope their data collection and analysis methods can be applied to future disaster zones anywhere in the world.

"Their work documenting life in the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster was exactly the kind of study that made sense," said Dana Cuff, who is lead principal investigator of the Urban Humanities Initiative and a UCLA professor architecture and urban design. "Their innovative, sensitive use of both visual documentation and data analysis is an excellent demonstration of the beauty of working across disciplines."

Kawano and Munaim got permission to enter the power plant through Jun Hori, a former news anchor with NHK, Japan's national public broadcasting corporation. In 2012, Kawano had assisted Hori, then a visiting scholar at UCLA, on a documentary about the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Hori became an outspoken advocate for the cleanup. He arranged for Kawano and Munaim, a former urban planning graduate student, to join him and three reporters on a tour of the plant.

On Dec. 10, the UCLA pair left Los Angeles for an 11-day trip through the evacuation zone, which includes the reactor site in Fukushima prefecture and neighboring Namie City. In contrast to the desolation of Namie—its entire population had fled—Kawano was surprised to find a bustling construction zone at the plant with 6,000 workers, wearing full-body suits and gas masks, clearing debris, repairing damaged structures and moving radioactive rods out of contaminated water into cleaner water.

Besides cleaning up the site, the other big task for Tokyo Electric Power Company, owner of the power plant, is to ensure that runoff water flowing into the Pacific Ocean is clean. "They have all these technologies, including an ice wall that prevents contaminated water from going into the ocean," Kawano said. "They trap the water in these huge containers"—as many as 3,000 of them are scattered throughout the site.

While the risk of getting radiation sickness was relatively low—"They say a day in the evacuation zone is equivalent to a visit to the dentist for X-rays," Kawano said—everyone on the tour had to remain in the van, wear surgical masks and gloves, and be subjected repeatedly to scans that tested for overexposure. "There was still an element of 'Are we really safe?'" he recalled.

Munaim and Kawano watched as thousands of workers followed a daunting daily routine of donning radiation suits, lining up to get scanned and traveling between the reactor site and a converted soccer facility where they lived.

Seeing this human element, part of what the field of urban humanities is all about, was what piqued their interest the most. "We wanted to know who lives there, who manages the space," Kawano said. "With government officials … what are their roles and how does that affect the people?"

Munaim and Kawano focused their research outside the plant in Namie, a city of 21,000 that had been exposed to radiation-tainted winds from the Fukushima plant. While Namie has since been deemed safe enough for government officials to work there, none of the residents have returned. The evacuation zone has a radius of 12 miles.

"In terms of urban planning, it's unprecedented," Kawano said. "Where are you going to find a city that's like the one in the movie 'Mad Max'? One hundred percent of your population had to leave within a day … and now, three years later, you're still trying to bring them back."

The two UCLA researchers recorded hours of video and audio footage in and around Namie, and they interviewed dozens of people who were affected by the destructive force of the earthquake and tsunami that was compounded by the nuclear disaster.

Kawano questioned residents about their feelings toward the Japanese government, which has been sharply criticized for its response. Some residents told the UCLA staffers they had been instructed to evacuate to areas that were more contaminated than the places they were fleeing.

"Farmers who have been literally deprived of their livelihood were angry because the government won the right to [host] the Tokyo Olympics in 2020," Kawano said. "The government is proclaiming there's no problem with Fukushima. The people feel betrayed by that because there still is a problem."

Mapping disaster recovery

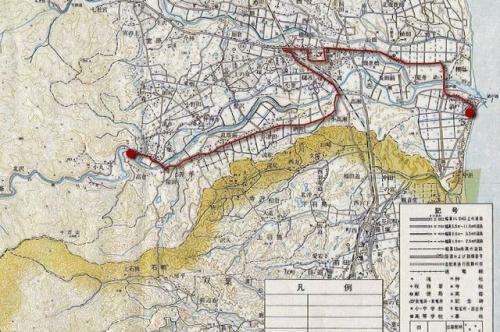

Poring over maps, the two men and city officials searched for a path through Namie that would allow them to gather detailed data about the effects of the multiple disasters on four regions—coastal, agricultural, urban and mountainous—in their short time there.

"It's a small town that was nearly wiped out," Kawano said. "You can see footprints of all the buildings … Houses were just lifted off and washed away. In many of the surviving structures, the first floors were gutted. You can see boats and cars in the middle of rice paddies."

But in some corners of Namie, crews were beginning to resurrect the deserted city. Kawano, who had already made three trips to the region to help faculty members at Japan's Niigata University measure radiation levels, saw approximately 100 trucks clearing debris and picking up cars and boats that had been stranded since 2011.

"When we went in March there was security all over the place," Kawano said. A public announcement blared repeatedly: "'If you are in the evacuation zone, you must leave by 4 p.m.' It's a booming voice out of nowhere, like in the 'Hunger Games.' Very, very eerie. Now all we heard were trucks and construction."

Now back at UCLA, Kawano and Munaim are busy working with all their data. In the short term, they built a website with photo montages, maps, short films and data visualizations to share with all the people involved; what they produce will be used in workshops at UCLA. "If anybody has an interest in doing fieldwork, we'll conduct a workshop on how to capture data and interviews," Kawano said.

To execute their long-term plan to help future disaster response planners, Kawano and Munaim have applied for a National Science Foundation grant to do a three-year study to develop a visual and a technical platform that can be used to educate students studying computer science and urban planning.

"We need to use Fukushima as a case study to determine best practices and other protocols," Kawano said, "and to figure out how they can be applied to disasters in other parts of the world."

Provided by University of California, Los Angeles