Observers slam 'lackluster' Lima climate deal

A carbon-curbing deal struck in Lima on Sunday was a watered-down compromise where national intransigence threatened the goal of a pact to save Earth's climate system, green groups said.

The hard-fought agreement sets out guidelines for the submission of national greenhouse-gas pledges next year.

But, the groups said, initially ambitious standards became weaker the longer the talks wound on.

In a tug-of-war between rich and developing nation interests, the end result was a "lackluster plan with little scientific relevancy," said WWF's climate expert, Samantha Smith.

"Against the backdrop of extreme weather in the Philippines and potentially the hottest year ever recorded, governments at the UN climate talks in Lima opted for a half-baked plan to cut emissions," she added.

NGOs and developing nations alike had hoped the agreement would compel rich countries to include information in their pledges on climate adaptation and other financial help.

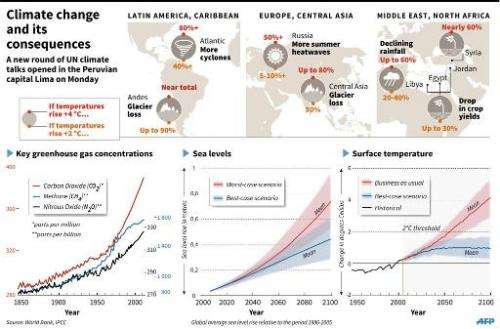

They had also sought a robust assessment of the pledges' aggregate effect and a mechanism for ramping up contributions, if they were judged inadequate to meet the UN goal of limiting global warming to two degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) over pre-industrial levels.

But expectations were mostly disappointed.

The talks, which spilled more than 30 hours into overtime, got bogged down early on in a fight over "differentiation"—how to divide responsibility for carbon cuts between rich and poor nations.

The outcome, said the US-based Union of Concerned Scientists, reflected "the bare minimum" to keep negotiations on the road to inking a climate-saving pact in Paris next December that will have the pledges at its heart.

Rather than imposing a requirement, the text merely "urges" parties to "consider including an adaptation component" in their pledges, and on finance similarly "urges" developed countries to provide support.

In a nod to poor country concerns, the new text did reintroduce a reference to "common but differentiated responsibilities" that had been dropped from earlier drafts.

Political expediency 'won'

"The package... puts in place a draft of a Paris agreement without narrowing down any of the difficult political issues that have plagued global efforts to address climate change for more than 20 years," said Oxfam.

"The deal does not require that the initial pledges parties make in 2015 reflect their fair share, does not guarantee that these offers will use common or comprehensive information, or have any mechanism to review whether they will prevent catastrophic warming or not."

To give the process a boost, rich nations will have to bring detailed plans for how they intend to meet a promise to ramp up their climate funding to $100 billion per year by 2020, said the observers.

"The limited progress that was achieved in Peru, in particular on the provision of financial support to poor countries to adapt to climate change or repair the damages from extreme weather events, is a big letdown," said Wendel Trio of Climate Action Network (CAN).

These critics also feared guidelines were too vague for cutting fossil-fuel emissions leading up to 2020, when the Paris pact will enter into force.

"The science is clear that delaying action until 2020 will make it near impossible to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, yet political expediency won over scientific urgency," said WWF's Smith.

© 2014 AFP