Biologist studies where and how animals cross busy Highway 67

Riding in the backseat of an SDSU-owned Jeep on Highway 67, just a little northeast of Poway, I point to a large bird perched on a wire.

"What kind of hawk is that?" I ask Megan Jennings, the vehicle's driver and a postdoctoral researcher working in the laboratory of SDSU biologist Rebecca Lewison.

"Can't look. Driving," she responds, eyes on the road, hands at 10:00 and 2:00—a picture of concentration. A few seconds later she adds with a laugh, "I know a lot of biologists who are the scariest people in the world to drive with because they're always checking out animals."

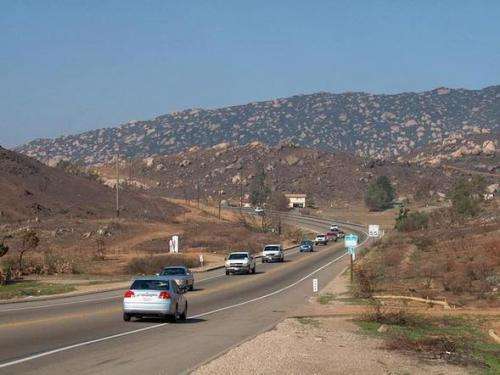

If every driver were as cautious as Jennings, we might not be out here in the first place. The stretch of Highway 67 between Lakeside and Ramona is one of the more dangerous passages in San Diego County. The population has exploded in those two cities in recent years, filling the road with speeding commuters during the daytime and a number of drunk drivers at night. A single-lane, undivided highway for most of its length, Highway 67 was never built to handle so much congestion.

Mulling medians

San Diego County is presently considering a number of options to relieve the congestion and improve public safety. Notably, the California Department of Transportation will begin talks in a few months on whether it wants to install median barriers, and if so, what kind. And in a few years, the discussion will likely begin in earnest about widening the highway.

While the county's human residents will all get some say in the proceedings, it's Jennings' job to be a voice for the wildlife. Numerous birds, lizards, bobcats, coyotes, skunks, and other critters live next to and near the highway, and whatever happens to the roadway affects them, too. Median barriers can slow their dash across the busy road, making them more likely to be hit by cars. A wider highway could also raise their chances of becoming roadkill.

So Jennings, funded by a grant from the California Department of Transportation, is investigating how animals in the area cross the highway, whether it's scrambling across the blacktop or running beneath the roadway through drainage culverts. Bobcats are of special concern, Jennings explains, as their presence (or lack thereof) is a good indicator of the overall health of the local ecosystem.

Say "Cheese!"

Today, I'm joining Jennings as she installs motion-capture cameras facing several culvert entrances, then measures and surveys the diameter of those culverts and the characteristics of the habitat on either side of the entrances. Jennings will eventually install 20 cameras in all between Lakeside and Ramona.

It's dangerous work. The culverts are often mere feet from the whizzing traffic, so Jennings wears a reflective orange vest and parks her car well off the main thoroughfare. It's also hot under the August sun, and rattlesnakes slither through the tall grass.

Over the next few months, animals traversing these culverts will trip the cameras and have their photos taken. Jennings will then analyze the findings to figure out what kinds of animals are crossing where, and what kind of culverts they're more likely to use.

She'll combine that data with roadkill data collected by other agencies to provide information that San Diego County can use when making decisions about how to change the highway. Depending on her data, Jennings says, they might go with one kind of median barrier over another, or install extra culverts.

"Fortunately, the people at Caltrans have been involved for a long time in these efforts, and they want to bring in this information during the planning stage, rather than after the decisions have been made," she says.

Provided by South Dakota State University