July 2, 2014 feature

Which happened first: Did sounds form words, or words form sentences?

The origins of language is, in some ways, more complicated to study than the origins of other biological traits because language does not fossilize or leave behind physical traces the way that bones and tissues do. However, there are other ways to study the origins of language, such as watching children learn to speak, analyzing genetics, and exploring how animals communicate.

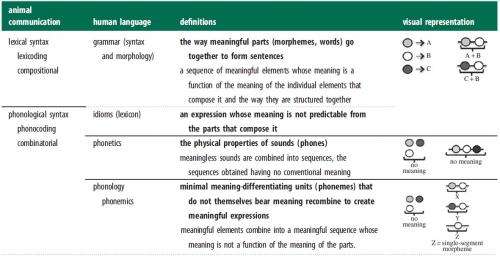

A recent review of animal communication in particular has yielded an intriguing discovery: while structured animal call sequences (for example, birdsong) are widespread, it is very rare that meaningless sounds produced by animals form meaningful sequences, as they do in human languages. This observation, combined with supporting evidence from human languages, has led linguists to suggest that syntax (the structure and rules of language, such as sentence structure) may have evolved before phonemes (the meaning-differentiating sounds that do not themselves have meaning).

The researchers, Katie Collier, et al., at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, have published a review paper on this idea that syntax evolved before phonology in a recent issue of the Proceedings of The Royal Society B. In their study, the researchers also hypothesize that syntax is a cognitively simpler process than phonology.

Building blocks of language

Collier, a PhD student at the University of Zurich, explains exactly what phonology and syntax are.

"A simple example for phonology would but the way the phonemes /k/, /a/ and /t/ that have no meaning in themselves and are used in many different words come together to form the word 'cat,'" Collier told Phys.org. "Syntax is the next layer where meaningful words come together into larger meaningful structures, such as 'the cat ate the mouse.' Phonology and syntax describe the way sounds form words and then words form sentences, rather than referring to the sounds and sentences themselves."

At first, the idea that syntax evolved before phonology seems counterintuitive, and it's true that it goes against the traditional linguistic view that phonology is simpler than syntax.

"It may seem counterintuitive, but it is not quite as simple as saying sentences evolved before grunts," Collier explained. "Animal calls or grunts most probably existed before 'sentences.' Most of these calls do not have meaning in the way that human words have meaning. A few have what we call functional reference, where they seem to denote an external object or event, such as a leopard for example. However, these calls cannot be decomposed into smaller sounds. They come as a single unit, unlike our words that are made up of several sounds that are reused in many different words. This is why we argue that there are no known examples of phonology in animal communication. On the other hand, as discussed in our paper, several species seem to combine these referential calls together to obtain new meanings in a similar way to very simple sentences in human language, which is why we argue that they may have a form of rudimentary syntax.

"I suppose a very simple way of looking at it would be to say that some animal species have 'words' that they can combine into 'sentences,' but their 'words' are simpler, less flexible than ours, made out of one block, rather than several reusable ones."

Monkey syntax

In their paper, the researchers reviewed a wide range of evidence that seems to support the origins of syntax before phonology. In the primate world, two species of monkeys—Campbell monkeys and putty-nosed monkeys—demonstrate this idea in slightly different ways. Both species have two main predators, leopards and crowned eagles, and both species give specific calls when they detect these predators. Campbell monkeys call "krak" at a leopard sighting and "hok" for an eagle sighting. For putty-nosed monkeys, the calls are "pyow" for leopard and "hack" for eagle.

While it's interesting that these monkeys seem to have specific "words" for different things, what's more interesting to linguists is that the monkeys modify these words to mean something different yet related. For example, the Campbell monkeys add the suffix "-oo" to both "words." The "krak-oo" call is given to any general disturbance, while the "hok-oo" call is given to any disturbance in the canopy. The researchers explain that the "-oo" suffix is analogous to the suffix "-like," changing the meaning of the call from "leopard" to "leopard-like (disturbance)." Due to how it combines two meaningful sounds to create a new meaning, this structure is an example of a rudimentary syntax.

The way that putty-nosed monkeys alter their calls is more complicated. Whereas "pyow" means "leopard" and "hack" means "eagle," a sequence of two or three "pyows" followed by up to four "hacks" means "let's go," causing the group to move. There are a few different explanations for how this sequence may have originated. One possibility is that the sequence may be an idiom, where the original sequence may have meant "leopard and eagle," later becoming "danger all over," followed by "danger all over, therefore let's go," and finally just "let's go." A second possibility is that "pyow" and "hack" may have more abstract meanings, such as "move-on-ground" and "move-in-air," and their meanings change depending on the context of the situation. Although neither explanation demonstrates with certainty that the putty-nosed monkeys structure their calls with a syntax, the sequences leave that possibility open.

Emerging human language

Further evidence in support of the idea that syntax evolved before phonology in human language comes from analyzing a variety of human languages themselves, including sign languages. As far as linguists know, all human languages have syntax, but not all have phonology. The Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language (ABSL) used by a small society in the Negev region of Israel is an emerging language that has been around for less than 75 years. Interestingly, it does not have phonology. For the ABSL, this means that a single object can be represented by a variety of hand shapes. However, the ABSL still has syntax and grammatical regularity, as demonstrated by the existence of rules for combining signs. Perhaps the presence of syntax but not phonology suggests that syntax originates first in the evolution of a young language, and perhaps also that it is simpler than phonology.

When looking at this hypothesis more closely, many aspects of it make sense. From a cognitive perspective, syntax may be simpler to process than phonology because it is easier to remember a few general rules than many phonemes. Having syntax allows speakers to express many concepts with only a few words. As language develops further, and still more concepts need to be communicated, phonology emerges to provide a larger vocabulary. The evolution of phonology may also be strongly influenced by cultural, rather than biological, evolutionary processes. The researchers hope to further develop these ideas in the future.

"To support our hypothesis that syntax evolved before phonology, a lot of work can still be done," Collier said. "Many animal communication systems are still very little understood or described and the more we learn about them, the more we can adjust and refine our hypothesis. From the linguistic side of things, studying more emerging languages (mainly sign languages) would show if there is a pattern for syntax to develop before phonology in human languages."

More information: Katie Collier, et al. "Language evolution: syntax before phonology?" Proceedings of The Royal Society B. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0263

Journal information: Proceedings of the Royal Society B

© 2014 Phys.org