Reptile Atlas a first for southern Africa

It took seven editors and 26 authors nine years to compile the first ever Reptile Atlas for all reptiles found in the southern tip of Africa. This huge collaborative effort resulted in the 485-page Atlas and Red List of the Reptiles of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland – a hardcover book launched recently that also contains the conservation status of the 421 recognised species and subspecies of reptiles found in these three countries.

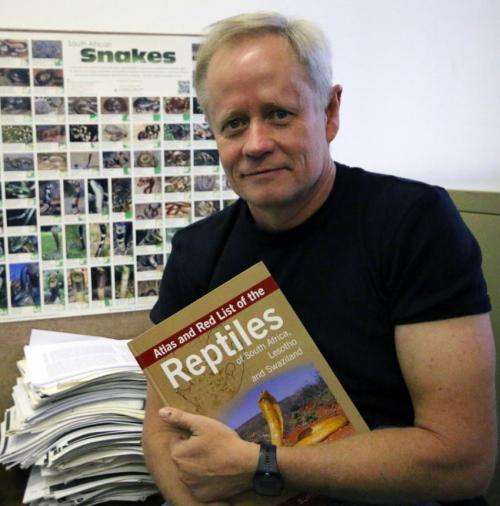

For one of the editors and authors, Associate Professor Graham Alexander from the School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences at Wits University, the full colour atlas is more than just a book. It is his brainchild as well as a giant step forward in the conservation of these cold-bloodied creatures he has loved since he first started collecting snakes at the age of eight.

"People truly thought I was nuts then, but as I grew older I could see a change in the public's attitude towards reptiles in general, and snakes in particular. There is no doubt people are becoming more aware of reptiles and the atlas is very important contribution to their conservation and protection," Alexander said.

He also worked on the Frog Atlas that was hosted in the Animal Demography Unit (ADU) at the University of Cape Town. Shortly after its release in 2004, Alexander started thinking of a reptile atlas and together with one of his MSc students, herpetologist Johan Marais, he ran a snake course at Wits University to raise funds for a start-up workshop. Most of the country's leading herpetologists attended the workshop and this massive research project was conceived.

Then the hard work started. Collecting and sourcing all the data to make the Atlas entries as up to date and relevant as possible, was a mammoth task, Alexander explained. Data about reptiles were sourced from about 400 people and 14 organisations – 135 512 records in total. The bulk came from museums and nature conservation agencies, as well as from private collections, academic institutions and published literature.

"The Atlas has the most up to date distribution maps (for reptiles) ever produced for the region. The data in these distribution maps represents all of the available data that we have collected since people started studying reptiles in South Africa," Alexander said. Citizen science

These, however, were not the only sources. With a 25% increase in the number of recognised species since 1988, Alexander and his collaborators knew they would need to crowdsource the public for some major citizen science involvement. This resulted in 61 volunteer field workers assisting in 24 field surveys over three summers from 2005 to 2008 – approximately 270 days of sampling effort.

It also led to the establishment of the SARCA Virtual Museum (VM) where the public could submit photographic records of reptiles and where a panel of 20 experts could log on, identify the reptiles and organise it in a manner analogous to a museum collection of voucher specimens.

"This citizen science participation has resulted in people focussing on areas where not much collecting has been done in the past. It filled the gaps in distribution maps and identified areas that need more attention. The virtual museum will also carry on, and is managed and run by the Animal Demography Unit at UCT. The virtual museum concept is now also being used for other atlases," Alexander said.

Conservation Assessment

A conservation assessment has been done for almost every single species contained in this book – a global assessment where the entire distribution is in South Africa and a regional one if southern Africa makes up only a small part of the range. It has been evaluated using International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) guidelines, based on detailed distribution maps, published literature and the collective expertise of leading herpetologists.

"Two previous 'Red Data' books only dealt with the species that are thought to be Threatened and these books were not very inclusive and neither were big collaborative efforts. Everything in the Reptile Atlas was peer-reviewed by the IUCN and internally recognized herpetologists. It is very inclusive, containing by and large all the species in this part of the world, with the exception of a couple of species South Africa forms only marginal parts of the range. "In some instances, we do not know what is happening with those species in our neighbouring countries and therefore could not do conservation assessments for them," Alexander explained.

Each entry also shows the taxonomy, habitat and conservation measures that need to be taken to protect a species. The maps show the distribution area of each entry and for the first time colour photographs of all the lizards, tortoises, terrapins, turtles, crocodiles and snakes found in this region are contained in one book – except for one entry.

The Günter's Dwarf Burrowing Skink (Scelotes guentheri) has only been seen in South Africa once – in the late 1800s when a single specimen was found by the Reverend Henry Callaway while travelling by ox-wagon from Pietermaritzburg in KwaZulu-Natal. It was described in 1887 by the Belgian-British zoologist, George Albert Boulenger (1858-1937). No specimen of this species has ever again been seen or found anywhere in the world and its status is therefore Extinct.

The Reptile Atlas is thus a "vital resource for researchers, conservationists and amateur naturalists alike", Valli Moosa, past president of the IUCN, said in the forward.

More information: The South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) published the book as the first in a new sister series to its well-known Strelitzia series, namely Suricata (meerkat). For more about the Reptile Atlas and how to purchase a copy, visit www.sanbi.org/news/sanbi-publi … -animal-publications

Provided by Wits University